On the edge of Chat Moss in Lancashire, in an area once full of collieries, lies the picturesque village of Astley Green.

In the heart of the village stands Astley Green Colliery Museum which, but for the foresight of Lancashire County Council and several leading figures within the community, would have suffered the same fate as the other collieries in the area – total demolition. It is a site that Fred Dibnah was familiar with and had visited regularly. It has to be said that he particularly enjoyed the fare on offer at the adjacent local chippy and the craic in the local hostelry.

It was the realisation of the uniqueness of the 3300hp twin tandem compound steam winding engine that brought the demolition of the redundant colliery to a halt. Accordingly the museum, which houses Lancashire’s only surviving headgear and engine house, now has listed building status. The preservation site and visitor centre is the headquarters of the Red Rose Steam Society, an active body, of which Fred Dibnah was a keen supporter.

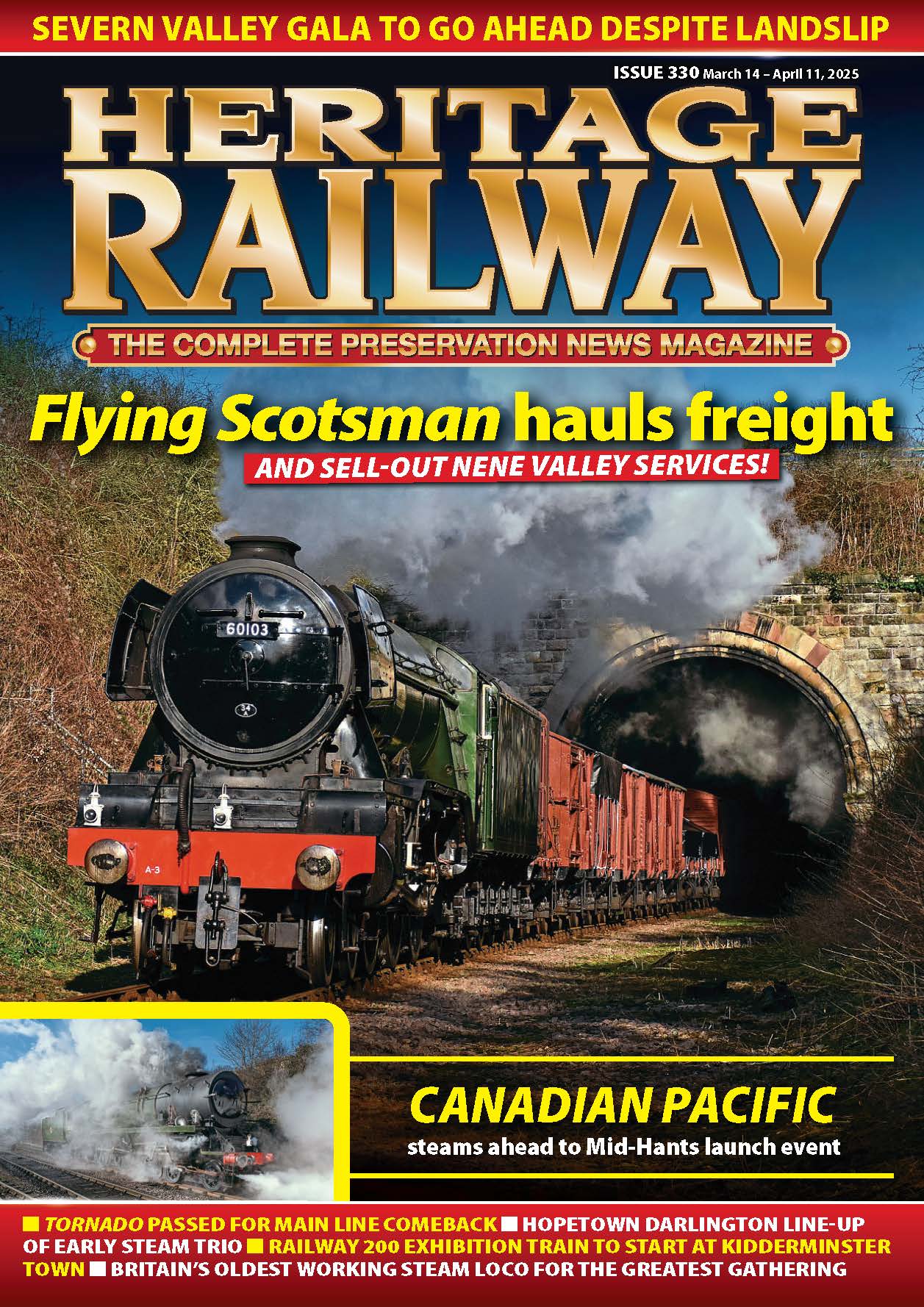

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

The museum occupies some 15 acres of the old colliery site and is virtually all that is left of the once-great Lancashire Coal Field. The low-lying landscape ensures that the museum’s 98ft high impressive lattice steel headgear can be seen clearly from the busy East Lancashire Road

(A580). A fitting memorial to days now past, the steam winding engine and its headgear complement the museum’s many other industrial exhibits, not least of which is the collection of 28 colliery locomotives, the largest collection of its type in the United Kingdom.

Richard Fairhurst explains why the nuts were well and truly roasted!

The Astley ex-colliery site was chosen by Fred Dibnah and the film crew as a suitable venue to visit at the beginning of his round-Britain tour. Thus the first real test run of the Aveling 8: Porter convertible terminated there after a successful and spirited run from Bolton. It was then serviced at the site over the weekend, prior to being lowloaded up to the Lake District, where it was required for more filming. It was on the fascinating coalmine site that Richard Fairhurst renewed his acquaintance with Fred Dibnah:

I have been fascinated with anything steam or mechanical for many years, probably back to when I was five or six years old. My late grandfather, who was a very patient man and fortunately indulged my childish curiosity, encouraged me or, should I say, put up with my endless questions. He was a great fan of Fred Dibnah’s and so, at an early age, I knew all about the local steeplejack who had restored a steam road roller.

I joined the Red Rose Steam Society when I was 13, went to my first traction engine rally that year and became well and truly bitten by the preservation bug. From then on I have been going to rallies, and a major part of my life now revolves around steam preservation. Like a good many, I bought the early Fred Dibnah books on steeplejacking and steaming right through my teenage years. By the time I was 15 or so I was probably quite an authority on him. I suppose you could compare it to another youngster worshipping a favourite rugby league player or cricketer. I read and inwardly digested every word.

Born in 1971, I do, of course, understand the need for, and the advantages of, modern technology, but I am also able to appreciate the engineering skills of the past and, like Fred, my hero was lsambard Kingdom Brunel. I joined the Lancashire Traction Engine Club (of which I am now, for my sins, membership secretary and website producer) when I was 18, and that marked a very memorable incident in my life. It was at one of their meetings that I had my first conversation with Fred; there I was, in the same room as the guy I had read so much about.

Around that time I got to know David Lomas, owner of Aveling eight-ton roller No 10753 (NU 3051), when I was still at university and had just turned 21. I began helping David with his engine at rallies and events on most weekends until about 1998. By that time I really wanted a steamer of my own and I set out in earnest to look for one and succeeded. On a very cold November afternoon in 1998 at Astley Colliery, I proudly first steamed the Fowler roller I had just bought, it was then called ‘Jenny’. It was then, and still is, my pride and joy.

That was on the Saturday and I slept well that night. with plans to road the machine around the village the following day firmly lodged in my mind. I was up early and soon had ‘enough on the clock’ to turn the wheels. As I was about to take to the road, who should just happen to turn up at Astley with some friends but Fred. He regularly popped down to Astley, normally calling at the pub opposite, and then having a wander round the site. He always came chatting with the boys working there and was genuinely interested in their projects.

The machine I now own was ordered new on 17 March 1925 by Aberdeen County Council as a DN1, 10-ton, 5hp, compound tar-spraying roller. It was delivered to them several months later on 28 May 1925. When supplied new as a tar-sprayer, it was fitted with Fowler-Woods tar-spraying gear, a differential, rope drum, fairleads, rim brakes and a full canopy. It was also supplied with two patent gritting machines, and Hecia tar boiler.

The gritters cost an extra £360 each, and the tar-boiler was a further £114-l0s. The engine, with a 10 per cent discount, cost the authority £1171, that figure being equivalent to about £40,000 in today’s money. During its working life this engine, along with four others supplied by Fowler’s, stayed in the Aberdeen area until entering preservation in 1968. All five engines survive today, although two of them are now in ‘showman’s guise’.

Since the engine was sold into preservation it lived in the Yorkshire area, until moving to Cheshire in the early 1990s, and then finally Lancashire to its present home. When I bought the roller it was a runner, so I never had the work of completely rebuilding it, but I have kept it in tip-top condition and that is something Fred often commented on. He also noticed that I had changed the name to ‘Nut Roast’ and asked me why I had chosen that ‘handle’. He roared with laughter when I told him the reason.

Like all kids with a new toy, I never wanted to put it away. I was forever cleaning and polishing the Fowler; every bit of bright metal was polished on every spare occasion, and still is. I was thinking about a choice of name and couldn’t really make my mind up, until one day after the cleaning session it came to me, literally in a flash.

I had been cleaning up the paintwork and I used a light solvent on a rag to wipe over the surfaces. I gave the rag another good soaking and, in doing so, I obviously spilled some of the solvent on my boiler suit. Somebody shouted ‘brew up’ and passed me a mug of tea, so I stopped work and sat on the boiler barrel in order to enjoy the welcome beverage. I should add it was a very hot boiler barrel.

Big mistake! As I sat there drinking my tea, the heat from the boiler warmed up that part of my boiler suit with which it had contact. A few minutes later, and completely without warning, there was a flash of bright flame as the solvent on the fabric ignited.

I have never taken a boiler suit off so quickly, but unfortunately not quickly enough – hence the name ‘Nut Roast’. As I finished telling Fred the tale he started to walk away, but not before exclaiming loudly the title of a 1960s hit song by Jerry Lee Lewis! He never let me forget that incident.

He was a great inspiration to a lot of people, in the steam job in particular and vintage machinery restoration in general, and he raised the level of interest in the subjects by his brilliant lV programmes.

He was an icon for the movement, on which he has certainly left his mark and I, along and with many others, certainly feel the better for having known him.

This article is an extract from the bookazine Fred Dibnah MBE: Remembered, available for just 99p – this weekend only!

Advert

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.