In the third part of his series about the dawn of steam, Brian Sharpe outlines how the larger railway companies increasingly moved towards establishing their own locomotive building facilities headed by chief mechanical engineers who were charged with providing motive power suited specifically for their employers’ requirements.

The 1830s saw the railway building mania accelerate dramatically. While many leading locomotive engineers formed specialist locomotive building companies, larger rail firms began to establish their own in-house resources.

Edward Bury was one of the engineers who set up his own locomotive building company. Born in Salford, Lancashire in 1794, he was the son of a timber merchant and was educated in Chester. By 1823 he was a partner in Gregson and Bury’s steam sawmill at Toxteth Park, but in 1826 he set himself up as an iron-founder and engineer. His original premises were in Tabley Street near the Liverpool and Manchester Railway’s (L&MR) workshops. He hoped to supply locomotives to that line, but opposition from the L&MR engineer, George Stephenson, thwarted this.

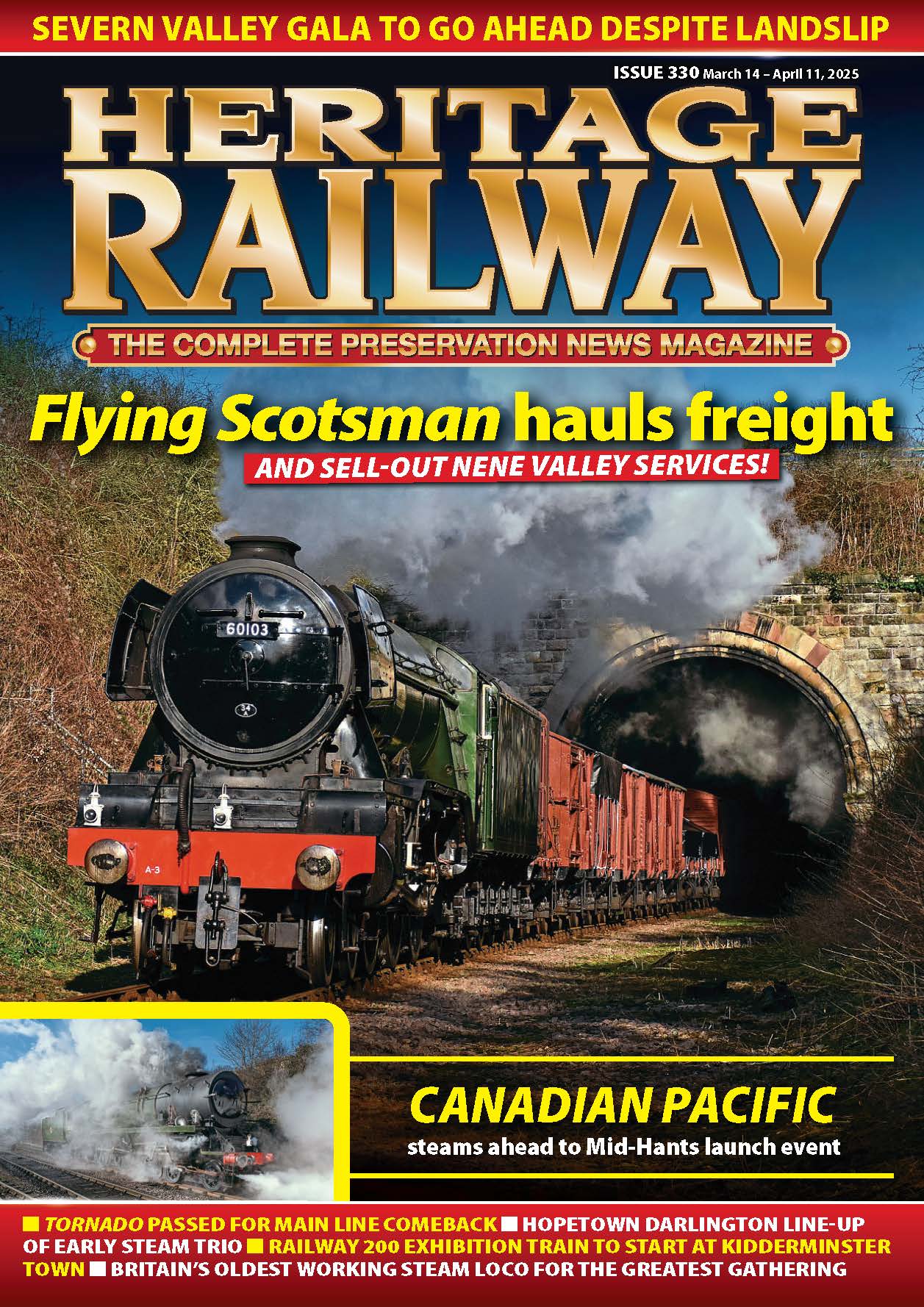

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

He moved his works to new premises in Love Lane, Liverpool, on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. Around this time he recruited as his manager James Kennedy, who had gained locomotive building experience working for George Stephenson and Mather, Dixon and Co.

The first locomotive built by Edward Bury and Co in Liverpool, Dreadnought, was intended to compete in the Rainhill trials, but could not be finished in time. His second locomotive, Liverpool, had four 6ft diameter driving wheels, and although it was tried on the Liverpool and Manchester, Stephenson thought the size of the wheels was dangerous.

Liverpool combined near-horizontal inside cylinders with a multi-tubular boiler and a round dome-topped firebox, but differed from what was becoming accepted practice in that it had a simple wrought-iron bar-frame inside the wheels, rather than wooden outside frames and inside iron sub-frames. This was a well thought-out and advanced design, which lasted.

Most subsequent Bury locomotives followed this same basic design, which was copied by other firms in Europe and the US.

Following the success of the L&MR, the next railway projects became ever-more ambitious. The London and Birmingham Railway (L&BR), linking Britain’s two largest cities, was an early project.

This railway took a different course to others, employing a contractor not just to build its engines and stock, but to operate its trains. Bury was chosen and he was awarded the contract in May 1836. The contract stipulated that the company would provide locomotives to Bury’s specification, while he would maintain them in good repair, being paid an agreed sum for each passenger and each ton of goods carried.

Bury provided specifications and drawings for a passenger engine and a goods engine, and these came from a number of manufacturers, including Bury’s own company. The arrangement never worked and, from 1839, Bury was employed as manager of the locomotive department in the normal way. The locomotive workshops had been established in 1838 at Wolverton.

Read more and view more images in Issue 249 of HR – on sale now!

Advert

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.