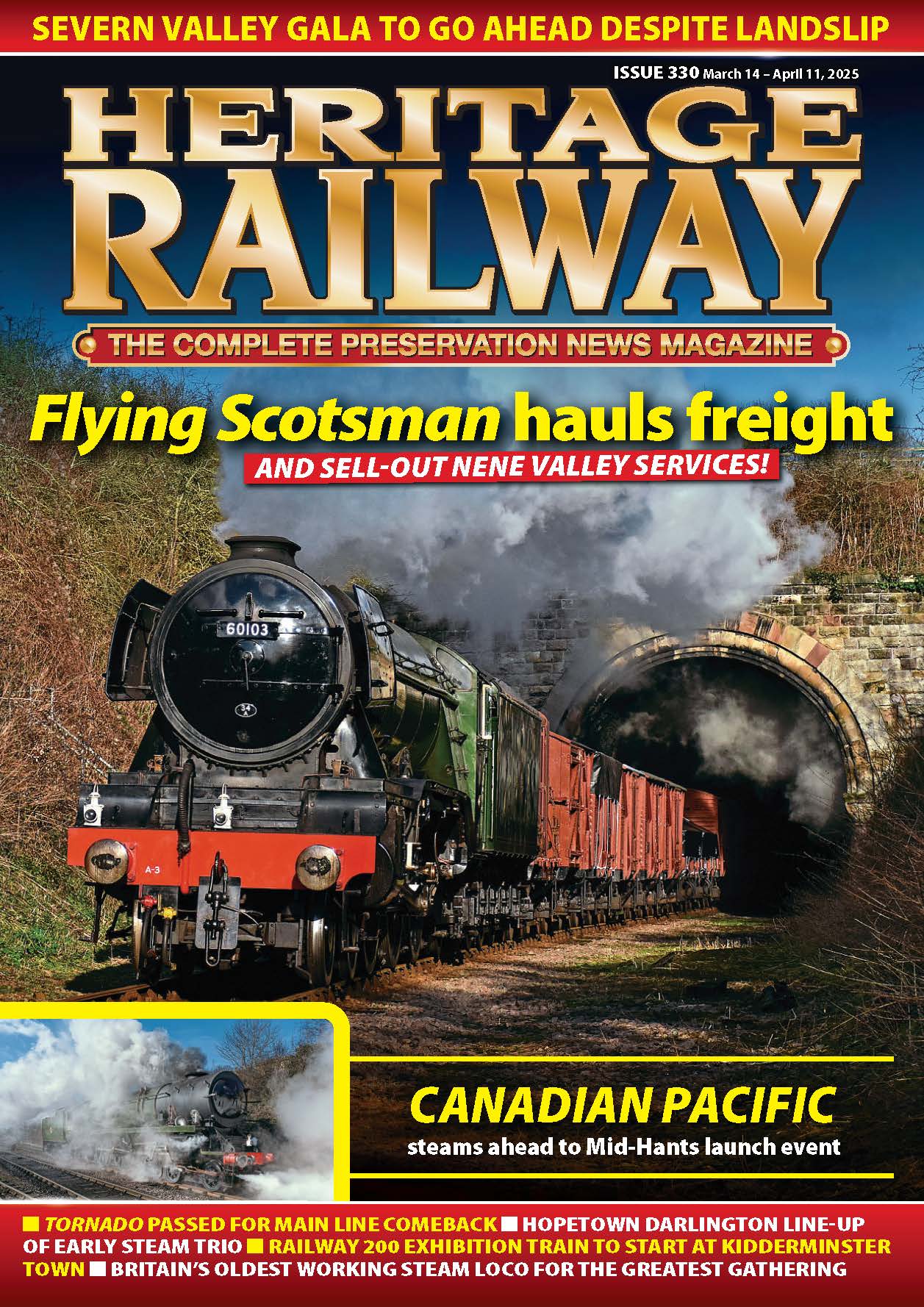

Many pre-Grouping steam engines soldiered on until the end of the 1950s but were then withdrawn faster than the locomotive works were able to scrap them. Robert Anderson recalls a trip to see some vintage steam power dumped in a remote corner of Lancashire in 1959.

By the mid to late 1950s most of us young trainspotters had become accustomed to the sight of short lines of veteran steam locomotives in store at most motive power depots. They were usually to be found tucked quietly away on one of the shed’s side roads or out of the way somewhere at the top of the yard. Sometimes a few of them were returned to traffic for occasional use to suit demands but for most of them it was the end.

From 1954 onwards DMUs had been taking over local and branch line services in several large areas of the country and diesel shunters abounded in many goods yards. On top of all this there was the continued alarming decline in freight traffic receipts, which had made the British Transport Commission hastily bring forward the 1955 Modernisation Plan with a headlong rush in 1958.

The lines of stored steam locomotives at sheds grew and grew and often spilled over into neighbouring sidings and goods yards. The withdrawal rates increased accordingly – so much so that by 1958 main locomotive works were struggling to cope with the breaking up of these old locomotives. Worse was to follow with more and more pre-Beeching line closures including in early 1959 the closure of almost the entire Midland & Great Northern system. Some 175 miles of railway, mainly in East Anglia, all in one fell swoop. These closures had the result of cascading relatively modern steam locomotives such as Ivatt 4MT 2-6-0s on to the remaining duties still entrusted to the older classes.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Heart-rending sight

The railway magazines of the day started carrying reports of large gatherings of redundant locomotives and one of the most poignant of these reports appeared in Trains Illustrated for December 1958 when a correspondent noted at the end of October that year an assembly of 21 locomotives awaiting scrap near Plaistow shed. This included almost the entire remaining fleet of the 0-6-2 and 4-4-2 tank engines built specifically for the London Tilbury and Southend line – and they had not even been officially withdrawn. This must indeed have been a heart-rending sight for the many aficionados of this most respected of railway lines.

Early in the new year 1959, most of these poor old engines found themselves towed north. Their destination would have been Crewe but the works couldn’t accept them and they were dumped on the disused Over & Wharton branch near the West Coast Main Line at Winsford eight miles north of Crewe. They were soon joined by no fewer than 14 LNWR Super D 0-8-0s five of which were from the former LNWR empire in South Wales having travelled from Pontypool Road, Tredegar, Llanelli and Swansea Victoria collecting one more at Shrewsbury en route.

The intended destination for all these engines was also, of course, Crewe Works and in his excellent article in Back Track January 1997, Professor Alan Earnshaw noted that of the 35 residents of this dump only one MAY have actually made it to Crewe Works. Winsford was, of course, one of the earlier dumps and the whole idea of 30-40 elderly steam locomotives lying more or less in the middle of nowhere rather appealed to me but on consulting a map I realised Winsford was probably not a suitable venue for a 14-year-old with no access to a car.

However, Crewe Works was not alone in being unable to cope with the ever-growing queue of condemned steam locomotives awaiting breaking up as Derby Works was now in a similar state. As many as 50 locomotives were dumped in and around the station and works with others at St Andrews goods yard and London Road sidings. These lacked the ‘middle of nowhere’ appeal and in any case access for photography could be a problem. Other dumps were situated out at Spondon, Borrowash, Chaddesden and Chellaston quarry but information was sketchy.

First major dump

It was a similar case in Scotland where the Glasgow and Edinburgh sheds had set up dumps at Longniddry, Polmont, Bathgate and Grangemouth but what little information there was appeared at best haphazard.

Apparently locomotives, which had not even been withdrawn, were out at these dumps and so were still shown in the Ian Allan shed books – a major source of information in those days – as still being at their parent depots. It was therefore difficult to ascertain just which location engines were at. All this uncertainty together with the sheer logistics and expense of getting there put me off Scotland despite the appeal of photographing locomotives with such fascinating names as Laird of Balmawhapple and Roderick Dhu and I turned my attention nearer to my home in Yorkshire.

Doncaster seemed to be coping quite well, in fact later on in early 1960 was able to help out the beleaguered Derby works by accepting delivery of Midland and early LMS locos from there at the rate of four a week. A good example was the fate of two Midland Compounds Nos. 41090 and 41102. They had been withdrawn at the end of 1958 and stored in St Andrews goods yard at Derby before getting to the actual works by April 1960. They were then towed north to Doncaster Works and eventually broken up in May or June 1960 some 18 months after they had been withdrawn.

Then I read about Heapey. It was possibly the first major dump for withdrawn locomotives and had been set up in mid to late 1958 being designed as a holding point for locomotives that Horwich Works could not deal with and were awaiting disposal to Crewe works or, as it later transpired, to the private contractors in the scrap metal industry. It ticked a lot of boxes for me as, being in the countryside sidings of the Royal Ordnance Factory near to Heapey station on the Chorley to Blackburn line made it fairly easy to get to from my home town of Bradford and very importantly the journey was affordable. The locomotives were behind padlocked gates and surrounded by high security fencing complete with watchtowers.

Heartening news

This was all good stuff to a 14-year-old schoolboy. I wrote to the stationmaster at Heapey to ask if it would be possible for myself and two school friends to visit these sidings with a suggested date of Saturday, May 16, 1959. To my great pleasure the kind stationmaster, a Mr Southworth if I read his signature correctly, wrote back with the heartening news that he would arrange for our party to have access to the locomotives on my suggested date.

We were on! Our train from Bradford Exchange was the 8.15am express for Liverpool Exchange, which would normally combine at Low Moor, with a portion leaving Leeds at 7.55am. The Bradford portion was usually worked by a 2-6-4T, which would uncouple at Low Moor, with the Leeds portion backing on and its Stanier ‘Black Five’ working the combined train forward to Liverpool. For some reason today was different. The load from Bradford was no fewer than 10 coaches, more than the usual combined portions and would have meant Southport’s ‘Black Five’ No. 44728 would be right on the platform ends with a cold start onto the 1-in-50 bank to Mill Lane and Bowling Junction. However, as this was one of the few trains on this line not to run to ‘Limited Load’ timings the crew would just have to make the best of a bad job.

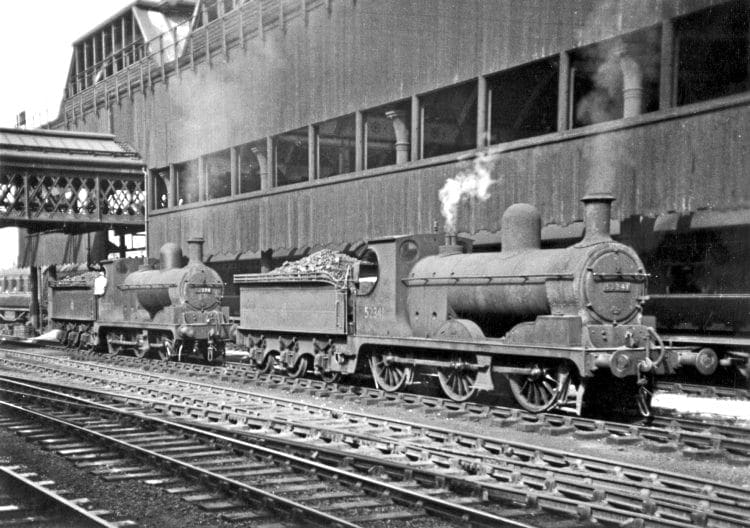

For obvious reasons the engine that had brought the empty stock in, Low Moor’s No. 42108 banked us throughout to Bowling Junction. Possibly the Leeds portion was running as an independent train in front of us which would account for a succession of signal checks between Hipperholme and Halifax making us six minutes late into Halifax Town station. The crew of No. 44728 now did indeed make the best of a bad job for even with this load they recovered five minutes and were but one minute late into Manchester Victoria. There was now ample time to photograph Nos. 52341 and 52270 standing in the locomotive loop, nicknamed the ‘wall side’ next to Platform 12 awaiting their next banking duty with freight trains facing the 1-in-59/47 climb to Miles Platting. To my mind the sight of these old L&Y A class 0-6-0s was a sort of ‘Welcome to Manchester’ for they were always there awaiting their call. Quite a few of them gave more than 60 years’ service.

Next it was the 9.55am train headed by Bolton’s 2-6-4T No. 42626 calling at all stations to Preston. Approaching Bolton we passed the shed and it was good to see Nos. 52393, 51498 and 52523 all in steam. Alighting at Blackrod some four minutes late at 10.41 we made our way to the first destination of our day – Horwich Works. We had no permit just loads of cheek, confidence or perhaps just sheer naivety. Being a Saturday there was almost an air of tranquillity about the locomotive works but even the Lancashire hospitality was stretched a bit here with the unannounced and uninvited arrival of three kids and no permit.

“What the heck can we do with them?” We produced our railway tickets and the letter from the stationmaster at Heapey and after a bit of head scratching and a few phone calls were told to wait in what seemed to us a most grandiose hall. Eventually we were afforded an abridged tour and noted a total of 53 locomotives including the 18in gauge Wren and the six works shunters. The most outstanding sight was that of No. 51343 receiving attention in the erecting shop. It must have been in just for casual repairs as it was withdrawn eight months later. No. 51343 belonged to quite an amazing class of locomotives. Originating in 1878 as an 0-6-0 tender engine to the design of Barton Wright the locomotive superintendent of the L&Y and built by Kitson & Co of Leeds. it was rebuilt as an 0-6-0 saddletank in 1892 under the jurisdiction of John Aspinall, the successor to Barton Wright, and survived until 1960.

No fewer than 230 locomotives were similarly converted and were known as the ‘Converted Tanks’. Thanks to the Keighley & Worth Valley Railway Preservation Society it is possible to compare an original Barton Wright 0-6-0 tender engine with one as rebuilt to an 0-6-0 saddletank by Aspinall although neither at the moment are in service. L&Y No. 957 built in 1887 finished its BR days still as a tender engine, No. 52044 being withdrawn from Wakefield in 1959 and purchased privately for preservation by Mr Tony Cox. It saw quite a lot of use on the KWVR and rose rapidly to fame as the ‘Green Dragon’ in the classic film The Railway Children. Now owned by the Bowes Trust this locomotive is currently on view in the museum at Oxenhope restored to its original L&Y condition.

Locomotive cavalcade

On the same railway, currently undergoing major work to bring it back into steam is the rebuilt saddletank version, L&Y No. 752 built in 1881 as a tender engine and rebuilt in 1896 as an 0-6-0ST. It was sold by the LMS as No. 11456 in 1937 to the Blainscough Colliery Co of Coppull in Lancashire, which later became part of the National Coal Board. Thankfully it was made available to the preservation movement in 1967 and after much work by members of the L&Y Saddletanks Fund, now known as the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway Trust, arrived at Haworth in 1971. It later participated in the locomotive cavalcade at Rainhill in 1980 as part of British Rail’s Rocket 150 celebrations.

Apart from the resident works shunters seven other L&Y locomotives were noted at Horwich including No. 51397 late of Sutton Oak, which was marked up for scrap but in fact saw several more years’ use as a stationary boiler at Liverpool’s Garston docks for heating banana vans to help the fruit ripen. It performed that role from 1960 to 1965.

Another locomotive noted, proving yet again something that anyone who has been even remotely involved in tracing the movements and disposal of withdrawn steam locomotives in the 1950s and 1960s, realises what a grey and murky area it is. The number in my notebook is No. 50865 one of seven L&Y Radial 2-4-2Ts withdrawn from the West Riding of Yorkshire in October 1958. They were Nos. 50725 and 50865 from Huddersfield; 50757, 50831 and 50855 from Low Moor and 50777 and 50818 from Sowerby Bridge. Everyone seems to agree that all seven were eventually sold on as scrap to a private contractor Albert Loom at Spondon near Derby because their intended destination for scrapping, Crewe Works, could not accept them.

The popular consensus is that at least six of them went first to a dump at Badnall Wharf adjacent to the WCML near Norton Bridge between Crewe and Stafford. The odd one out is No. 50865, which is the locomotive my notebook indicates as being at Horwich on May 16, 1959. Peter Hands in his What Happened To Steam series has been somewhat discredited for one reason or another but I think on this occasion he could be correct for he shows No. 50865 as stored at Huddersfield from its withdrawal in October 1958 to May 1959 then being broken up by Looms at Spondon in June 1959. Was No. 50865 perhaps despatched from Huddersfield to Horwich works in error in early May and then sent direct to Spondon?

Our last port of call in this quick tour of the works took us to the paint shop where we were treated to the sight of the preserved Furness Railway 0-4-0 tender engine No. 3 ‘Coppernob’ withdrawn way back in 1900 together with the first locomotive to be built at Horwich Works, in 1889, Radial 2-4-2T No. 50621 withdrawn from Manningham shed in September 1954 and cosmetically restored as L&Y No. 1008 in its original red-lined black livery complete with dummy wooden tapered chimney to replicate the original. Not that we could see any of it for the whole locomotive was draped in sheeting and looked almost ghostly. Interesting that Horwich was looking after its own product rather than poor old ‘Coppernob’. Both locomotives are now on display in the National Railway Museum at York.

It was now time to hurry to the neat single-platform terminal station at Horwich where we caught the three-coach 12.13pm all stations train for Blackburn headed by Bolton’s 2-6-4T No. 42635. We alighted at Heapey the first station after Chorley on the now-closed line to Blackburn and were greeted on the platform by the stationmaster, Mr Southworth. This made us feel very important. He informed us that there had been 23 locomotives but eight had recently been sold leaving 15 for us to photograph. He asked if we could be as quick as possible because he didn’t wish to incur the wrath of the Ministry of Defence.

Woebegone residents

So we ended up taking 16 photographs in 15 minutes which didn’t give us much time to take in the sad sight of 15 forlorn engines all in one line awaiting their fate. Some of these we could remember seeing in steam in our even younger days. Gates were unlocked with due ceremony but there were no signs of any MoD police so we were quietly confident. Mr Southworth stayed with us all the time as we photographed the woebegone residents. The 15 locomotives concerned were Nos. 51512, 51423, 52216, 51415, 52268, 51457, 50647, 51404, 52237, 43890, 51546, 50712, 43984, 51316 and 40178. Twelve L&Y, two Midland Railway and one LMS. The latter apart from being far and away the most modern engine there was yet another mystery.

It had officially been transferred to Horwich Works presumably as a works shunter from store at Manningham in February 1959 having been made redundant like so many of this class by DMUs. However, it was not officially withdrawn until October 1961 in a mass cull along with 38 other members of this less-than-successful class. Despite this official withdrawal date of October 1961 here it was, well and truly dumped at Heapey by May 1959. Most, if not all, of the locomotives here did seem to go from their parent shed to Horwich Works first but whether No. 40178 was ever used there as a works shunter appears doubtful. Of the 15 engines at Heapey on this day it now transpires that nine of them were officially destined to be broken up at Crewe but were dumped at Heapey because Crewe refused to accept them.

It was now time to bid farewell to the helpful and friendly stationmaster and begin our journey home. Another of Bolton’s two-cylinder Stanier 2-6-4Ts, No. 42569, was at the head of the three-coach 1.58pm Chorley to Blackburn stopper and did well to convert a two-minute late departure from Heapey into a half-minute early arrival at Blackburn for there was a one and a half mile slog at 1-in-65 from Heapey to Brinscall. We had ample time to wander round Blackburn station with its two large island platforms and three bays with a large overall roof straddling the middle. It was all very impressive but not particularly attractive we thought and, of course, the roof has now gone.

Long and damp

Our next train arrived behind yet another Stanier 2-6-4T No. 42559 of Lower Darwen working the 2.21pm Hellifield to Manchester Victoria. We made a point of travelling in the front coach and were looking forward to hearing some hard work from the front as No. 42559 tackled the three-mile climb from Darwen through the long and damp Sough tunnel to the summit at Waltons sidings mainly at 1-in-74/69. We were not disappointed but with a load of just three coaches the locomotive made fairly light work of the climb and time was easily kept throughout to Manchester.

While at Clifton Junction station, we were reminded of the almost unbelievable work performed in L&Y days by members of the same class of engines we had earlier photographed awaiting their fate at Heapey. I refer of course to the L&Y 2-4-2Ts, which performed such amazing feats of haulage with among others the famed 4.25pm business train from Salford to Colne. Loaded with up to 10 coaches, these brave little engines and their magnificent crews were booked to cover the 29 miles of most difficult railway between Salford and Burnley nonstop in 49 minutes including severe service slacks at Clifton Junction, Bury and Accrington.

These forbid any rushing at banks and after braking for the 30mph turnout at Clifton Junction it was then all out up the 1-in-88/97 to Bingley Road, soon followed by the long climb from Bury Bolton Street through Ramsbottom then the left-hand fork at Stubbins Junction with its fearsome 1-in-73/85 to Helmshore and finally the 1-in-68 up to Baxenden. After all this hard climbing there then began the frightening two-mile descent at 1-in-40 to Accrington with its 5mph slack at the bottom round the sharp right-hand curve at the station leading onto the viaduct.

Any runaway here would have been catastrophic. To make matters even more difficult for all concerned on Mondays Wednesdays and Thursdays only, this train conveyed slip carriages for Accrington. These rear two coaches were slipped at the foot of the two-mile descent of 1-in-40 from Baxenden on the tight curve in Accrington station, which was so tight that exchange of hand signals between enginemen and guards had to be passed on by a third man stationed on the platform. As Eric Mason in his wonderful book The Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway in the Twentieth Century writes, it “was a very ticklish business”. One which probably only the L&Y would dare to do! Most of this line is long closed except the section from Bury through Ramsbottom to Stubbins Junction – which is a junction no more – as part of the East Lancashire Railway.

Flushed with our success of getting round Horwich Works without a permit, we decided to try our luck at Newton Heath shed as we had plenty of time before heading back to Yorkshire. The train service especially on Saturdays to Newton Heath was sketchy, so Flt Lt Aidan LF Fuller’s most useful British Locomotive Shed Directory was consulted and we caught a No. 65 or 82 bus to Dean Lane. I would have been no doubt hoping it to be one of Manchester Corporation’s lovely Crossley DD42 double-deckers with their distinctive bodywork. For me these most attractive red-and-cream liveried double-decker buses were the epitome of the Manchester bus and in their own way were just as much a ‘Welcome to Manchester’ as the L&Y class A steam locomotives at Victoria station.

We must have impressed the Newton Heath running foreman; perhaps the letter from the stationmaster at Heapey while irrelevant to Newton Heath may nevertheless have done the trick for within 40 minutes of arriving at Victoria station we were photographing L&Y A class 0-6-0 No. 52230 in steam in the shed yard. It was just approaching its 65th birthday and made a pleasant comparison with its incapacitated sisters at Heapey. The foreman had advised us to look out for visiting Royal Scot 4-6-0 No. 46135 of Crewe North. Named as it was The East Lancashire Regiment its very clean condition made us wonder if it had been on exhibition somewhere in the area. There were 63 locomotives on shed only five of which were of L&Y origin. However, even older than No. 52230 was No. 51371 and notably as the oldest engine on the shed it was in steam. No. 51371 was to soldier on for more than another year and on its withdrawal in March 1961 at the age of 82 from its original condition or 67 years from its rebuilding date, records showed it had achieved 1,625,248 miles. Not bad for a small shunting engine.

Back to Manchester Victoria then our train home. The 6.30pm Liverpool Exchange to York was an Agecroft job and it was a strange train. Always a Stanier ‘Black Five’ working throughout with a most variable load, this was down no doubt to it being one of the few Calder Valley route trains not running to ‘Limited Load’ timings; anything from six coaches to nine and sometimes with a van. Today was an exception even for this train with the load being 11 coaches and a van some 387 tons tare. However, despite the load we left Manchester Victoria on time at 7.26pm behind No. 44987 being banked throughout over Smedley Viaduct to Thorpes Bridge Junction by one of the Victoria pilot engines, 4F 0-6-0 No. 44311 – a wise precaution with this load. The crew did well for we would have been early into Sowerby Bridge had there not been a dead stand for signals on the approach to the station.

Renowned for fast running

The last leg of our journey was the Halifax and Bradford connection off the York train. Due away from Sowerby Bridge at 8.30pm it was renowned for fast running to recoup a late start if the York train was running late. Today there was no such problem but Halifax was still reached in six minutes with a departure at 8.38pm. Today’s diesel units are allowed the same timings. At Low Moor engines were changed for reasons best known to the motive power authorities. 2-6-4T No. 42073, which had brought us so energetically from Sowerby Bridge, was exchanged for Fowler 2-6-4T No. 42409 and despite this engine change arrival at Bradford Exchange was only one minute late.

In the preparation of this article I have consulted numerous books and magazines. For an informed yet highly readable book I recommend The Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway in the Twentieth Century by Eric Mason (Ian Allan 1954). I am told the author was an employee of the L&Y, which explains the wealth of information. For an in-depth study Barry C Lane’s Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway Locomotives (Pendragon 2010) is a must. Last but by no means least I must congratulate Ian Bartlett, Stephen Leyland and Vernon Sidlow of the 73156 Standard 5 Group for its book Requiem at Ince (Book Law 2012). This is the most concise book I have read yet regarding that most difficult subject – the disposal of British steam locomotives in the 1950s/1960s.

To get the picture captions as accurate as possible I have consulted various copies of Trains Illustrated, Peter Hands’ What Happened to Steam series, Steam Motive Power Centres Derby (Book Law 2008) and Back Track magazine January 1997 for Alan Earnshaw’s Down in the Dumps article plus, of course, my own observations.

Read more News and Features in Issue 230 of HR – on sale now!

Advert

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.