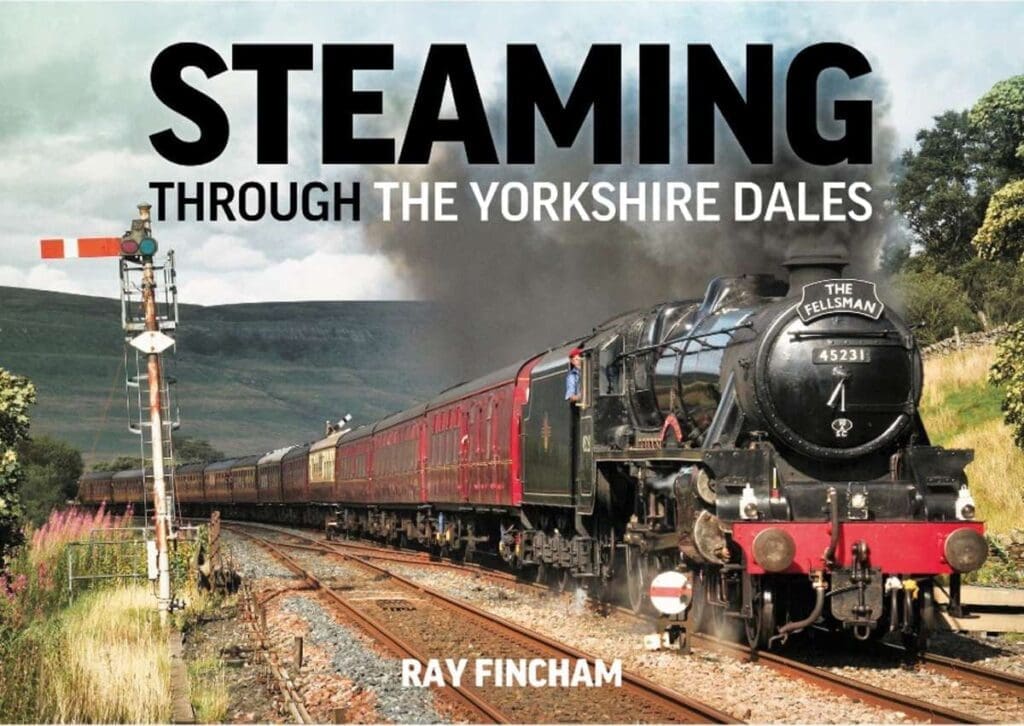

Ray Fincham takes a look over the history of steam transportation in the Yorkshire Dales.

The topography of the Yorkshire Dales has long made travel through the district problematic. Transport links have evolved slowly over millennia to serve locals and travellers from further afield, paths and tracks for those on foot and horseback, pack-horse trails and drove roads for long distance trade. Over the course of time, roads were made for horse-drawn carriages and carts, improved in the turnpike era when income from tolls paid for their regular repair. The hand of the canal pioneers rested lightly on the Dales, but then came the railway builders. At first, lines crept into the fringes and valleys, primarily to serve the need of local commerce and indigenous populations. Then in the mid-1870s, through this high landscape, came a mainline connecting Settle in the south with Carlisle to the north; a vital link to complete a through-route between London and Scotland.

Much has been written of the Settle and Carlisle railway and its building, but suffice to say that competition for a direct route from London to the north independent of its rivals motivated the Midland Railway Company to undertake the construction of a line through such challenging terrain. Whatever the genesis of this ambitious engineering project, we have been gifted the wonderful legacy of the railway builders. Those with knowledge of the line will be aware of its many tunnels, bridges, cuttings and embankments, and of the stations and their ornate buildings, but the eye of the casual observer is drawn to the viaducts. First amongst these is Ribblehead which has become a honeypot for tourists, its twenty-four arches rising magnificently 104ft above Batty Moss. Other such constructions are of note, Dent Head, Artengill and Dandry Mire viaducts, all major edifices built with considerable difficulty in hostile locations. In fact, the whole route has left an indelible mark, its bold man-made structures contrasting with and enhancing the natural beauty of the Yorkshire Dales.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

The future of the Settle and Carlisle railway came under threat in the 1980s, by which time other lines which once served the Dales had been lost. British Rail claimed that the route was no longer financially viable, was little used, and that the cost of work required to keep the line open was too great. The plight of the route was raised in the public consciousness, and a long hard-fought campaign to retain the railway was thankfully successful; by 1989 the future of the line was secured.

In recent years, the popularity of steam hauled railtours has grown, and the Settle & Carlisle enjoys its fair share of such services. Throughout the year two or three workings may be observed each month, and during high summer it’s no longer unusual to see a couple or more steam tours each week. It’s these trains and their locomotives which are the subject of this book as they traverse the thirty-three miles of route which lie within the Yorkshire Dales National Park between Langcliffe in the south and a point a little way beyond Crosby Garrett in the north.

Each locomotive featured has its own story, of its manufacture, its service life, and with the single exception of the recently built Tornado, the story of its survival. Steam locomotives were withdrawn from service at a rapidly increasing rate during the 1960s as they were replaced by diesel and electric traction, and by August 1968 steam had been eradicated from Britain’s mainlines. Fortunately, a good number were saved from the cutter’s torch. Some locomotives were spared because of their historic value or fame, Flying Scotsman being the prime example, purchased from British Railways by businessman Alan Pegler who had reached agreement for running rights on the mainline; or Duchess of Sutherland and Royal Scot each bought by Billy Butlin for static display at his holiday camps. The survival of others however was far more random.

A lucky circumstance had occurred when a South Wales scrap-man purchased hundreds of redundant locomotives and thousands of surplus wagons to feed the many smelters thereabouts. By great good fortune, wagons are easier to reduce to scrap than are locomotives, and so, as the workforce laboured to cut up the former, the latter lay gathering rust in his Barry Island scrapyard. These randomly procured engines, bought and sold simply on the basis of their scrap value, gradually increased in worth as they became a scarce commodity and, in the fullness of time, many were rescued, released into preservation one by one as the necessary funds were raised. Over a period of twenty-three years, no fewer than 217 of the 297 engines consigned to Woodhams’ scrapyard were saved, in effect forming the nucleus of the preserved steam fleet in operation today.

Turning now to the challenging terrain through which the railway was driven. The natural geology of the Yorkshire Dales is that of limestone overlaying shale with millstone grit forming the high tops. The last ice age shaped the landscape when glaciers scoured out the ‘U’ shaped valleys, leaving the higher points of Whernside Ingleborough and Pen-y-ghent for the enjoyment of the present-day rambler.

Human activity has also played its part in shaping the Dales. The working landscape of the area has evolved slowly over the last six thousand years or so, the relatively recent network of walled fields and field barns being perhaps the most prominent man-made feature of the Yorkshire Dales. The small enclosures seen near settlements in the valley bottoms date from the 17th century, but by the 19th century many of the fells were enclosed, often by long straight lengths of dry stone wall, open grazing then limited to the loftiest ground. In recognition of the beauty and unique character of this limestone landscape, both natural and man-made, the Yorkshire Dales was awarded National Park status in 1954 to conserve and enhance the area’s natural beauty, wildlife and cultural heritage. In 2016, the National Park grew by almost a quarter, extending west along the Lune Valley and northwards to include Mallerstang, Wild Boar Fell and the Howgills.

Finally, on a personal note, my interest in steam engines and railways in general started at an early age, and in my youth I was one of the few amongst my train spotting peers to be equipped with a camera. My interest in railways led to an apprenticeship with the Chief Mechanical and Electrical Engineers Department, and I went on to spend the whole of my working life in the railway industry. But steam had gone, and I took little note of the diesel and electric locomotives which replaced them.

Much has changed since my train spotting days when my camera was used to capture images of sheds full of working steam engines; of Kings, Castles and Halls restarting passenger trains out of Snow Hill, or an 8F trundling through Water Orton with a train loaded with coal for Birmingham. However, when I came to live in the Yorkshire Dales my interest in steam locomotives was rekindled, and I found myself roving the stations and fells in search of a favourable viewpoint when a steam special was due.

It’s not only railways which have changed since my youth, so too has my camera. In those former times, I had been very happy when I was able to upgrade from the family Box Brownie to a second hand 35mm camera of no particular pedigree, and to develop my black and white film in a tiny darkroom set up in the cupboard beneath the stairs. The images herein were captured using basic Canon DSLR cameras, the EOS350D and latterly, an EOS2000D.

With the advent of digital photography, results can be manipulated in ways unimaginable in the days of emulsion paper, developer and fixer, and although I have resisted the temptation of presenting an idealised image, I have at times indulged the age-old tradition of ‘burning in’ smoke, steam and thundery skies to enhance the atmosphere. The results of my labours are here arranged for the most part in the order witnessed by a traveller heading north over this remarkable section of the Settle and Carlisle line as it rises and falls over the roof of England.

You have just read an extract from Ray Fincham’s brilliant book Steaming Through the Yorkshire Dales. Grab a copy today and enjoy over 90 stunning photographs showcasing the beauty and history of steam in the Yorkshire Dales.

Advert

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.