Bill Parker’s Flour Mill workshop at Bream, which is widely renowned for its steam locomotive restorations and overhauls, celebrated its 20th anniversary with a stupendous gala at the nearby Dean Forest Railway. The event saw three of its best ‘customers’ return to thrill the crowds at one of the most successful events in the line’s history, writes Robin Jones.

They have driven steam on real suburban trains in Poland, run over the Hungarian main line and even piloted the Venice Simplon Orient-Express out of Budapest with a GWR small prairie.

The Flour Mill workshop team made the award-winning steam trips on London Underground over the past few years a huge success.

In early July, however, they were back on home territory, to showcase some of the finest fruits of their labours over the past two decades.

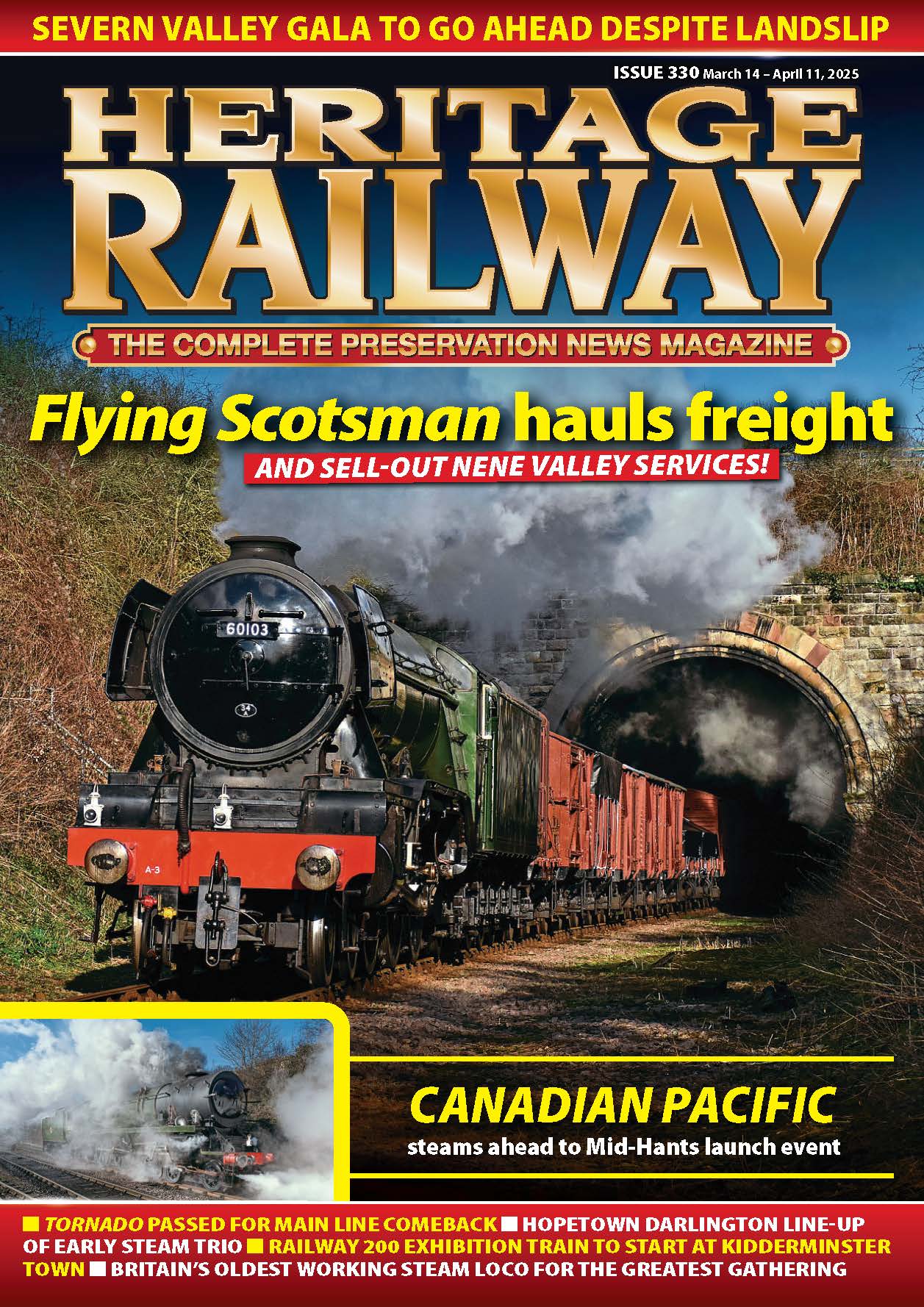

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

The Flour Mill, set up by chartered surveyor Bill Parker in 1996, joined forces with near neighbours, the Dean Forest Railway, for a special two-weekend gala.

The event, over July 1-3 and 8-10, celebrated 20 years of the workshop, which has become a market leader in the repair and maintenance of Victorian steam locomotives.

The guest locomotives were the National Collection’s LSWR Beattie well tank

No. 30587 and T9 ‘Greyhound’ 4-4-0 No. 30120, both of which were restored to working order by the Flour Mill and now based at the Bodmin & Wenford Railway, and the big star of the Steam Back on the Met runs, the Buckinghamshire Railway Centre’s Metropolitan Railway E class 0-4-4T No. 1.

All three ran between Lydney Junction and Parkend over the two weekends, hauling both service trains and special charters for invited guests.

The first weekend saw a rare chance to visit the Flour Mill and tour the workshops. Entry cost £5 per person, only valid with a train ticket for the day, with visitors taken to Bream by bus from Parkend, and all proceeds going to the local hospital and hospice.

The event turned out to be one of the most successful in the history of the line. A total of 1654 passengers were carried, although there were many VIP guests too. The ticket revenue for the gala totalled £31,112, with catering bringing in another £8519 and shop sales amounting to £5866.

In addition to the six gala days, the T9 also ran on Wednesday, July 6, and an evening photo charter was hauled by the well tank.

Among the VIPs on July 1 was supportive local MP and the then Government Chief Whip in the House of Commons, Mark Harper, who took a breather from the post-EU referendum leadership tussles of both main parties at Westminster to visit the railway and see for himself the strides now being made towards making it into a major tourist draw for his constituency.

He joined mega-enthusiast Sir William McAlpine, his wife Judy and other invited guests on a special train comprising GWR inspection saloon No. W80943, which was repainted and refurbished last year, and the Dean Forest’s Royal Forester carriages, for a three-course lunch, ranging from Bulgarian buffalo canapes to fish and chips from Frydays in Bream.

Bill is chairman of the Hawksworth Saloon group that owns No. W80943 and the largest shareholder, yet this was the first occasion that he had been able to use it for its real purpose

For once not on duty at the regulator or in the machine shop was Flour Mill foreman and chief engineer, Geoff Phelps, who has been with the Flour Mill since July 1, 1996, all 20 years. Also present was the other man who started that day, skilled machinist, Phil Davies, now back at the works part-time.

A similar outing ran the following day, this time for patrons of the National Railway Museum, including former long-serving head Andrew Scott, marking its partnerships with the Flour Mill over the years, many sponsored by retired banker Alan Moore.

Bill commented that the relationship began with the boiler overhaul of GWR broad gauge replica Iron Duke in 1996, and was still going strong – apart from the locomotives at the gala his two favourites were probably building a new working replica of Rocket using the old one’s wheels and cylinders in 2009 and, of course, valuing Flying Scotsman before the NRM bought it – but he won’t say for how much!

Not present was the Flour Mill’s GWR small prairie No. 5521, the centrepiece of those fabled European adventures, which is about to see out the last few months of its 10-year-boiler ticket with the Midland Railway Trust at Butterley, and will again star in this year’s Underground steam runs alongside Met No.1 between Wembley Park/Harrow-on-the-Hill and Amersham on September 10-11 (see separate story, News) in London Transport livery as No. L150.

Although L150 is the Flour Mill’s flagship, as there was really only room for three visiting locomotives, and as the DFR already has No. 5541 in service, it was decided not to bring it to the Forest of Dean this time. However, there could be a special farewell for No. 5521/L150 on the Dean Forest Railway, possibly on October 15-16, before its ticket expires on October 19.

Why Swindon moved to the Forest

The history of the Flour Mill workshop dates back to 1986, when British Rail Engineering Limited decided to close Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s GWR workshops at Swindon, a move that devastated the great railway town. However, Swindon’s legacy of steam was not ended that easily. Bill, an enthusiast since his boyhood days who had made his fortune in the USA, met up with old friend Ivor Huddy, who had previously helped him buy two steam locomotives.

The pair drew up a blueprint to save at least part of the works where steam locomotives could continue to be maintained, and when British Rail eventually sold the works site to Tarmac Properties, Bill agreed a deal to get the lathes running again.

The new Swindon Railway Workshop was owned by Swindon Heritage Trust, a charitable body, which was allowed to occupy up to four acres of works buildings.

In 1989 it was becoming apparent that the NRM would have to find a home for much of its collection while the roof of its main building at York was replaced, and Bill persuaded Steve Reeves of Tarmac Properties to allow the works to be used as a temporary home for much of the National Collection.

The 1990 ‘National Railway Museum on Tour’ exhibition at Swindon saw masterpieces such as GWR 4-6-0 No. 6000 King George V and unofficial record breaker No. 3440 City of Truro (which the Flour Mill would later help overhaul in time for the centenary of its unofficial 100mph run of 1904) displayed alongside BR Standard 9F 2-10-0 No. 92220 Evening Star and the world’s fastest steam engine, LNER A4 Pacific No. 4468 Mallard.

Bill had been introduced to the late Princess of Wales, who told him that her children William and Harry were “mad on trains”, and inevitably an invitation to Swindon followed. The princes stayed for two hours: climbing up on the bufferbeam of King George V, and riding precariously on the back of the works traction engine up to City of Truro.

It had been hoped that the heritage version of Swindon works would become permanent. However, when the ‘Thatcher Boom’ of the late 1980s burst and the value of commercial developments collapsed, Tarmac served Swindon Railway Workshop with notice to quit.

Protests and bad publicity eventually forced a U-turn by the landowner, but by then the relationship between Bill Parker and the Tarmac Properties management had broken down completely; Tarmac subsequently agreed a deal with the trust’s former works manager, Bill Jefferies, and Hull businessman Ken Ryder, to take up a tenancy inside the works.

The pair established a new operation entitled Swindon Locomotive Carriage & Wagon Works, which in turn was later taken over by engineer, Steve Atkins, who rebranded it as Swindon Railway Engineering.

Meanwhile, the original Swindon Heritage Trust remained without a home until 1994 when Bill bought a semi-derelict engine house at the former Flour Mill Colliery at Bream in the Forest of Dean, a Grade II listed building dating from 1908.

It was restored with the help of a small grant from the Rural Development Commission to accommodate the trust, which began operations again – and initially, still traded under the name of Swindon Railway Workshop, even though it lay in deepest Gloucestershire, the county nextdoor to Wiltshire.

The ‘new’ Swindon works’ first job, ironically, was overhauling the NRM’s Iron Duke replica, which was completed in time for museum’s annual dinner in September 1996.

The workshop then completed the rebuilding of GWR 0-6-0PT No. 4612 from little more than a pile of spare parts, frames, a boiler and wheels, two of them with spokes cut, after it was bought from Barry scrapyard and used as a ‘donor’ locomotive to keep sister No. 5775 running on the Keighley & Worth Valley Railway. Its eventual sale to the Bodmin & Wenford Railway Trust, negotiated by Bill with retired London banker and that railway’s prime sponsor, Alan Moore, led to a partnership that continues to this day.

The trust then won the contract to carry out the museum’s replica Stephenson’s Rocket’s 10-year boiler overhaul, which was also completed on time to a tight schedule.

The Flour Mill building has no rail connection to the main line, with the existing rails laid on an old 1825 tramway trackbed, and is reached only by a road through the woods.

Although the Flour Mill is capable of overhauling engines of any size (the two largest so far being David Shepherd’s 9F No. 92203 Black Prince and most of WR 4-6-0 No. 6960 Raveningham Hall) it is ideally suited to medium-sized engines, and to some extent has specialised in tank engines, especially Victorian ones.

The relationship with the NRM grew with the urgent repair of Captain Bill Smith’s GNR J52 0-6-0ST No. 68846 for its centenary in 1999.

The big breakthrough came with the Alan Moore-funded overhaul of one of the two surviving Beattie 2-4-0 well tanks, No. 30587, which had been on loan to the South Devon Railway for static display inside Buckfastleigh station museum for many years.

Its triumphant return to steam at Bodmin in 2002 opened the door for more work of this kind, including the resteaming of the 1899-built T9, which had been considered a ‘mission impossible’ by others because of its cylinder block problems.

In 2009, the Flour Mill effectively entered the new-build steam sector. Commissioned by the Science Museum, it produced the abovementioned new working replica of Stephenson’s 1829 Rocket.

In 2010 talks began about potential celebrations for the 150th anniversary of London Underground, the world’s oldest subway system.

It was obvious that the ideal choice for any steam specials over the Underground system would be Met No. 1. Chosen to overhaul it was none other than the Flour Mill, which had undertaken its previous overhaul and knew the engine inside out.

Not only that, but the Flour Mill’s steam drivers provided the footplate crew to take it through the tunnels during celebrations, which began in early 2013, and saw a complete wooden-bodied Victorian train running in between standard electric service on the tube.

Bill also played a part in the preparations for the Met 150 celebrations, arranging to bring No. 30587 from Bodmin to London for a series of clandestine night-time trips to see whether the operation of steam on an ultra-modern electric underground system was feasible. It was, and heritage-era history was made, with the Flour Mill team in the thick of everything.

Next stop Cinderford

The successful gala also provided a brilliant showcase for the 4 ½-mile heritage railway’s own plans to progress deeper into the forest.

Aboard the VIP special, Mark Harper heard in detail about the £8-million scheme to push north from Parkend to the original branch terminus at Cinderford via Speech House Road.

Upwards of £500,000 is likely to be needed for a barrier level crossing to the immediate north of the current railhead at Parkend, similar to the new one at Norden Gates on the Swanage Railway.

The dividends for local tourism are all but 100% guaranteed. Cinderford would join the likes of Bridgnorth, Rawtenstall, Pickering and Minehead, where the local steam railway contributes a major slice of the tourist economy. Extending the DFR into Cinderford would place it on the map.

The town could become a destination for incoming main line charters, decanting 500 people a time into its pubs and shops.

Furthermore, it could pave the way at a future date for ‘real’ community services to run from there to Lydney and maybe into Gloucester, making Cinderford a commuter settlement and a more desirable place to live.

Large mines nearby

Cinderford was fairly late in the day to get a railway station. The town itself is relatively new, having first been laid out following the construction of Cinderford Ironworks in the late 1700s, and the opening of large mines nearby.

A rail connection to the forest town was first mooted in 1876, but nothing happened for a quarter of a century.

The Severn & Wye Railway opened Cinderford New station on July 2, 1900, the first train being an excursion to Weston-Super-Mare via Parkend, Lydney and the Severn Railway Bridge.

The station was later operated by both the Midland Railway and GWR after a loop via Cinderford Junction from the Forest of Dean Branch at Bilson was completed in April 1908.

Passenger services to Cinderford ended on November 1, 1958, the last one headed by GWR

0-6-0PT No. 7750.

The station stayed opened for freight traffic until the line was finally closed in 1967. Now, half a century later, there are serious plans for the railway to return, and have an even bigger impact than it did first time round.

The railway is also looking into the possibility of buying land at the former Travis Perkins’ builder’s yard alongside the line on the northern outskirts of Lydney. Once rail connected, the site could provide space for a carriage shed, essential for keeping stock under cover and extending its operational life.

Read more Features, News, Views and Opinion in Issue 230 of HR – on sale now!

Advert

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.