In another occasional series of historical reviews of ‘Big Four’ locomotive engineers, Cedric Johns highlights the career of Frederick W Hawksworth, who succeeded Charles Collett in 1941…

In retrospect, the final years of Frederick Hawksworth’s engineering career at Swindon were cut short by political events beyond his control when the 1945, postwar general election swept Clement Attlee’s Labour government into power.

Three years later the Great Western’s proud traditions were replaced by a newly-formed, politically-managed organisation proclaiming it to be British Railways.

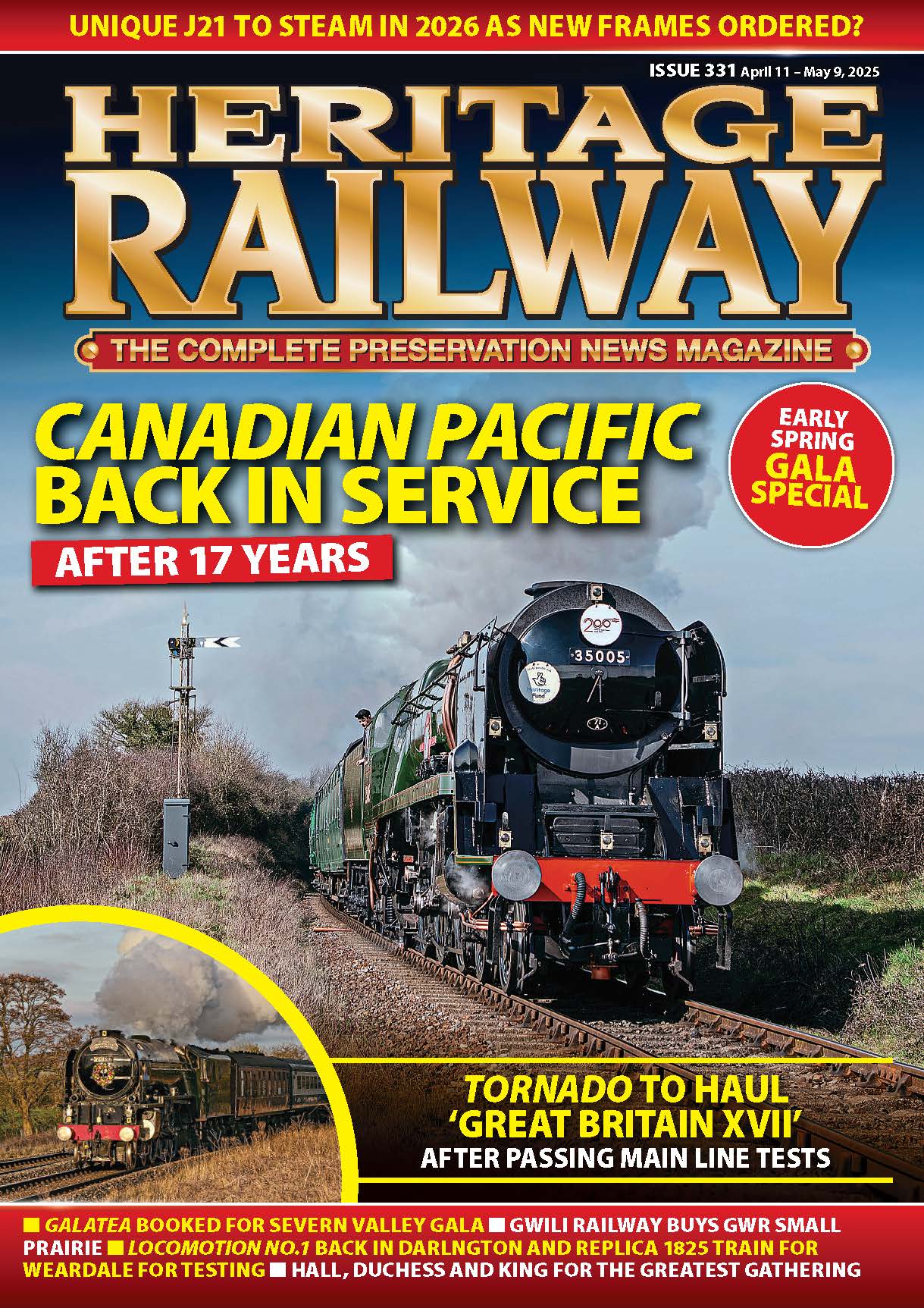

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Not only did Nationalisation threaten Swindon’s reputation for excellence and all that it had stood for over the generations starting with Gooch and Brunel, it spelled the end of the ‘Big Four’ as we had grown up to know it collectively and individually.

‘Vote Labour’

Ironically, thousands of railwaymen contributed to this historic change in the country’s railways by voting Labour. Indeed, as a small boy ruling off names and numbers in my very first ABC I well remember seeing numerous Swindon-built engines carrying the politically motivated message ‘Vote Labour’. In the majority, the message was given prominence by the use of work-stained smokebox doors suitably daubed in white chalked capitals…

But back to the beginning, Frederick Hawksworth was a Swindonian by birth and a Great Western man by family tradition. His father was a member of Swindon’s drawing office team and his uncle a foreman at Shrewsbury. It was he who first introduced the young Frederick to the power of steam when he took him for a cruise on the River Severn in his coal-fired launch…

As it was, Hawksworth entered Swindon Works as an apprentice in 1898, a period when William Dean was the Great Western’s chief mechanical engineer, assisted by Churchward.

After seven years spent in the testing house he moved to the drawing office in 1905. This was fortunate because Churchward, who had succeeded William Dean, was a regular visitor and noted Hawksworth’s capabilities.

An engineer at heart, FW had previously received the Gooch award for machine drawings from the Great Western’s sponsored technical institute. This was followed by a first class-with honours-award given by the Royal College of Science for machine design.

Building a Pacific

On entering the drawing office one of his first tasks was to set out the general arrangements for The Great Bear, Churchward’s venture into the world of big engines, the first 4-6-2 to be built at Swindon and for that matter, this country. This experience prompted Hawksworth’s enthusiasm for building a Pacific during his senior years in office.

But that had to wait for another 18 years – promotion was slow in those days – something to do with ‘dead man’s shoes’ if you remember. So, it was 1923 when FW was given the title of assistant to G H Burrows, then the company’s chief draughtsman.

The wait was almost over. When Burrows retired two years later, Hawksworth became head of the drawing office team working closely with Charles Collett. It is said that after a briefing meeting with Collett it was Hawksworth who laid down drawings for the King class 4-6-0s, including many of the working details for the prototype No. 6000.

When Collett and his assistant, John Auld, retired in July 1941, Hawksworth reached the pinnacle of his career, becoming the Great Western’s last chief mechanical engineer. Unlike his predecessors, FW’s promotion coincided with the Second World War, which had committed Swindon to producing work for the military on the orders of the Mechanical Engineer’s Committee of the Railway Executive, a group of senior railwaymen drawn from the ‘Big Four’ to manage all four railway companies throughout the period of war.

These commitments stopped any thoughts of normal locomotive development for the first few years of Hawksworth’s reign. Instead, he had to oversee the building of the final batch of Collett 69XX Hall 4-6-0s and the construction of 80 LMS 8F 2-8-0s, the latter being allocated to the Great Western for use on freight traffic thoughout the duration. That was rather ironic, as it was a case of Stanier returning to Swindon in the guise of one of his inspired designs.

In addition to routine maintenance, the wheel shop turned out 12,500 circular bearings for armoured cars. In the plate shop 17,000 parts for Hurricane aircraft were machined prior to delivery.

Sections of Spitfires

In another section of the works, 60,000 bombs sized up to 4000 pounders were built for the RAF. Part of the wagon frame shop was given over to the construction of light landing craft for the Royal Navy. A section of the same shop was given over to Short Bros. for the production of ‘ready to fit’ sections of Spitfires.

To protect the works, light anti-aircraft gun positions were established on the rooftops along with 400 staff volunteering for fire watching duties. As the war progressed there was a change of direction back to locomotive repair and construction to overcome the problem of a growing shortage of serviceable motive power.

As it was, repairs were kept to minimum to ensure engines were turned round as quickly as possible. Only essential work was carried out before locomotives were returned to traffic. These were given a new coat of black paint on their smokeboxes to indicate their passing through the works. Enginemen’s humour reckoned that such engines had been ‘soled and heeled’.

Having said that, as the war years dragged on the Mechanical Engineers Department placed an emphasis in the construction of new freight and shunting engines. This resulted in a batch of 33 more 38XX heavy freight 2-8-0s being built.

When the time came for looking ahead the highly successful mixed traffic Collett Hall class 4-6-0s gave Hawksworth the opportunity to introduce some of his ideas as he planned for the future.

Simplify the construction

Convinced that more Halls would be required – with some changes to the design features, he realised that to improve on Collett’s design would be no easy task but that some developments would be necessary to improve performance in postwar conditions, poor coal for starters. So he developed a higher degree of superheat, which he considered necessary to enable the ‘new’ Halls to combat the negative effects of poor coal out on the road. He also decided to simplify the construction of the new engines by changing to main plate frames throughout with a simple plate frame bogie. Of special note is the fact that he opted for a higher degree of superheating in the well proven No. 1 boiler linked with a three-row superheater with headed regulator. These changes were incorporated in the first of the 6959 ‘Modified Hall’ class introduced in 1944.

No. 6959 Peatling Hall was outshopped in black without nameplates, Instead the 4-6-0’s classification – Hall Class – was painted on the central wheel splashers. A Collett tender was attached to the engine. Commencing with Nos. 6959-6970 (1944), the 4-6-0s ran without nameplates for two to three years. In traffic Hawksworth’s ‘new’ Halls were an immediate success, showing their ability to steam freely with the inferior coal then available.

Poor fuel continued to be a problem on all railways when peace returned and Hawksworth was still developing superheating when the Great Western was nationalised on January 1, 1948.

He then became subservient to the new Railway Executive, RA Riddles from the LMS being appointed as a member of the Executive for mechanical engineering.

FW retired in the December of 1949 but locomotives of his design were constructed at Swindon until 1956 and his work on improved superheating was further developed and successfully applied to King, Castle and County class 4-6-0s.

But that was not the end to the Hawksworth story. In 1945 rumours had begun to circulate among enthusiastic observers and linesiders that a large passenger engine was on the drawing board at Swindon.

As usual, details of the new design were exaggerated by conversation up and down the line reaching the point of a super King emerging from the works.

When the engine was unveiled to the waiting enthusiasts there was a feeling of disappointment when it was shown to be nothing more than a two cylinder 4-6-0. It was, in effect, the final development of Churchward’s Saint class 4-6-0 born some 43 years earlier…

Hawksworth’s thinking behind the design indicated a change of attitude in Swindon’s approach to the future. In particular, the new 4-6-0 was pressed for 280lbs boiler pressure as opposed to the normal 250lbs – but later reduced to 250lbs – and fitted with double blastpipe and chimney and non-standard coupled wheels of 6ft 3in diameter, the engine appearing with one of Hawksworth’s

newly-styled flush-sided tenders.

Easier to maintain

The key to the new design was that the two enlarged cylinders provided tractive effort – 32,580lbs at 85% – and new No. 15 boiler – which was approaching the power of a

four-cylinder Castle but built more cheaply and easier to maintain.

After Hawksworth had retired, alterations to the superheater elements thereby reducing the superheating surface – and the total heating surface – and by reducing boiler pressure to 250lbs, tractive effort was lowered to 29,090lbs. In addition, the No. 15 boiler was equipped with a hopper-type ashpan providing a quick method of dropping ashes on shed.

Like his ‘Modified Hall’ class, Hawksworth used mainframes of plate steel throughout, the cylinders were cast separately and there was a fabricated steel saddle for the smokebox and front end of the boiler.

To lift wartime gloom the engine, No. 1000 County of Middlesex, was turned out in lined Brunswick green, complete with a

copper-capped chimney, almost to the day that the hostilities in Europe ended.

Shortly after the Counties were built in numbers at Swindon between 1945 and 1947, my family moved to the South Coast following my father who had joined BOAC’s engineering base at Bournemouth Hurn. Taking every opportunity to return to my old haunts and friends, I well remember the day that I copped three new Counties in a matter of hours.

The summer holidays provided the excuse for me to revisit those old haunts and friends and so it was that four of us who bought sixpenny return tickets to Westbury where, after walking around two sides of the shed we made it to that point that the West of England main line dived under the bridge carrying the foothills of the Upton Scudamore bank en route to Salisbury…

We had not settled in our favourite vantage point for very long before the first Paddington-Exeter-Plymouth fast appeared from the shallow cutting curving the cut off towards us. King or Castle? No, it was a County, No. 1010 County of Carnarvon… Smiles all round, none of us had seen the engine before and, whisper it quietly, it was the first sighting of a County for me!

As the afternoon wore on we had plenty of trains passing in both directions to hold our attention, never mind what might be running on the Salisbury line, be it a Hall, Castle or a tired old ROD 2-8-0 struggling against the gradient with a banker assisting.

County of Denbigh

As for the main line, with most trains being hauled by Kings or Castles we had seen before, it happened. Without warning a train appeared from that shallow cutting with 4-6-0 No. 1012 County of Denbigh at its head, another ‘cop’ for all of us.

Time to go home. Retracing our steps we arrived at the station with time to spare and the hope that an Exeter-Paddington semi-fast would be on time pulling into Platform 4 and, in doing so, would prevent our train, an

auto-train with a ‘48’ 0-4-2T positioned at the rear, from departing from Platform 3.

Well, it worked. Standing at the far end of the platform, eyes strained along the long straight to where the ‘London’ would appear around the curve of the joining ‘home’ line by the South Box, we saw the distant shape of the train making its way towards Platform 4.

As it drew closer we could see the engine wasn’t the usual King or Castle. Much to my delight, the bufferbeam numbers read 1000, yes it was Hawksworth’s prototype, County of Middlesex, double chimney, long extended splasher and horizontal nameplate, my third ‘cop’ of the afternoon. My friends smiled with me but they had already seen it before!

As usual, the crew took advantage to put the bag in for a quick top up – and it had to be quick – as the platform inspector signalled the train to pull up to accommodate the last two or three rearmost carriages on the platform.

Hand-signalled to stop, No. 1000 halted opposite the North Box, a feather of steam rising from the 4-6-0’s safety valve. Within a minute the red starter signal dropped by 45 degrees. A moment later the yellow distant followed suit. Given a piercing whistle and green flag from the guard, the County’s driver whistled a short acknowledgement and opened the regulator…

Gathering speed, the 4-6-0 worked its train under the road bridge then crossing the pointwork, took the line curving right towards the Berks & Hants line.

To cap the afternoon, a few minutes later, when we entered the leading auto coach, the driver, who must have been watching us, slid his communicating door open and invited us to join him in his driving compartment…

If my tale brings back memories so much the better.

In hindsight it is said that the Counties cannot be seen as an entirely successful design in relation to Swindon’s progressive developments. History suggests that Hawksworth intended his design to be the precursor of greater things, possibly in the shape of a 4-6-2 built with 6ft 3in drivers

and 280lb boiler pressure, but we shall

never know…

In their original form the Counties were prone to poor steaming – especially when driven hard by crews not used to handling the new 4-6-0s – and when rostered for similar duties to Castles they were found not to be such free runners at higher speeds compared to the four-cylinder engines.

However, when test house engineer Sam Ell put the class through extensive trials in the late Fifties, the 4-6-0s showed a marked improvement after all were fitted with double blastpipes and chimneys to proportions worked out during the trials.

Having said that, the Counties performed to the highest standards working heavy trains on the Birkenhead route between Wolverhampton and Shrewsbury regularly taking the Shifnal and Hollinswood banks – two miles at 1-in-180 and then three miles at 1-in-100 – with loads of up to 500 tons behind the drawbar; the 4-6-0s doing a job they were designed for.

The same applies to the consistently changing switchback route between Penzance and Plymouth when, rarely exceeding 60mph on a route where gradients ranged from

1-in-80 to 1-in-50, Counties managed loads

of 350 tons with apparent ease.

Gas-turbine locomotive

I should add that in 1946 Hawksworth turned out a batch of Castles with three-row superheaters commencing with No. 5098 Clifford Castle and No. 5099 Compton Castle followed by Nos. 7000 to 7007, the first two fitted with standard sight-feed lubricators, the remainder with mechanical lubricators.

The sight-feed lubricators fitted to the 50s harked back to Churchward’s time and were in everyday use by drivers brought up in the traditional manner. When the 7000 series were put into service, crews soon complained they were sluggish by comparison…

In 1946 the Great Western took the unprecedented step of considering a change in its motive power plans.

Accompanied by general manager Sir James Milne, Hawksworth visited the works of Brown-Boveri in Switzerland to assess the merits of a gas-turbine locomotive.

Rather like Churchward, who experimented with French designs, an order was placed for No. 18000. Delivered to Swindon – by then BR Western Region – in 1950 it arrived after Hawksworth had retired.

In addition to 4-6-0s, Hawksworth introduced a series of tank engines. In 1947 he received a request from the running superintendent for more 0-6-0PTs based on the reliable 5700 class. Hawksworth agreed to this and submitted the request to the general manager in the annual building programme with a diagram of the class. Sir James Milne objected, saying that a more modern appearance was needed.

So, the design was modified to create the 9400 class. Only 10 were built in Great Western days, the remaining 200 by British Railways, which sub-contracted the actual construction to Robert Stephenson & Hawthorns, Bagnall & Co and the Yorkshire Engine Company.

At the time, British Railways was considering a complete change to diesel locomotives for shunting duties, the lifetime of the 9400

0-6-0PTs was short from the beginning and the first withdrawal was made in 1959.

By contrast, Hawksworth came up with a definite departure from the established Swindon concept of pannier tank design with his 1500 class of 0-6-0PT, which he intended to be used as a 24-hour shunter that would not need to go over a pit for oiling.

Its leading dimensions were similar to the 9400 series but without superheating. The wheelbase was short to allow working in sidings, yards and over sharp curves but the class was restricted by a long overhang at each end of the coupled wheels.

Despite their austere appearance, a lack of running boards, platforms and splashers, the new 0-6-0PTs were the heaviest tank engines built for the Great Western, weighing 58tons 4cwt. Only 10 were built at Swindon and delivered after Nationalisation during Hawksworth’s last year in office. Yet the engines were well liked by crews and performed well, but they came too late to

have much impact on future Western Region steam operations.

Hawksworth’s final design was the light passenger and shunting 1600 class 0-6-0PT built to replace life-expired 2021 class

0-6-0PTs.

Seventy engines were put into service, starting with the first batch, Nos. 1600-1619 introduced in 1949 followed by 1620-1629 in 1950, 1630-1649 in 1951 and 1650-1659 turned out in 1954/5.

The engines were, in fact, the last of the traditional Great Western locomotives built at Swindon for British Railways. Thereafter, only BR Standard steam emerged from the works.

Hawksworth had been heavily involved in locomotive testing; modernising the Swindon plant and developing practices, which were later adopted as BR standards. He embraced modern traction to the extent of ordering the first GWR diesel shunters and two experimental gas turbine-electric locomotives Nos. 18000 and 18100.

No. 18000 was finished in black and silver but was later painted in Brunswick green and lined out in red and white.

Lengthy repairs

Used extensively on the Paddington-Bristol route the locomotive was often called in for lengthy repairs and was eventually withdrawn in 1960, but has been preserved.

A second gas turbine locomotive, No. 18100, was purchased from Metropolitan-Vickers and delivered to Swindon in 1951.

Withdrawn in 1958, the locomotive was converted to electric power as No. E2001 and used for crew training on the London Midland Region.

Like Churchward, Hawksworth never married but he gave much of his time to

local affairs and was the fourth consecutive chief mechanical engineer to become a JP

in Swindon.

Having given all of his adult life to all things Great Western, his career as the company’s chief mechanical engineer was cut short to just eight years with the advent of Nationalisation.

Who knows what might have been accomplished had the politicians not interfered with our railways.

One might argue that Hawksworth’s Halls and Counties were of no great account but they represented his forward thinking – if one studies the details – leading up to bigger, more powerful engines.

According to sources close to Swindon, the drawing office had prepared drawings for a 4-6-2…

Advert

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.