In 1904, Great Western Railway icon No. 3440 City of Truro could have been hailed as the fastest locomotive in the world after being clocked at 102.3mph – yet the company waited 18 years to confirm the feat, because of public fears about speeding trains.

This is just one of the many in-depth features found in the new book by Robin Jones, Legendary Locomotives, available now from Classic Magazines.

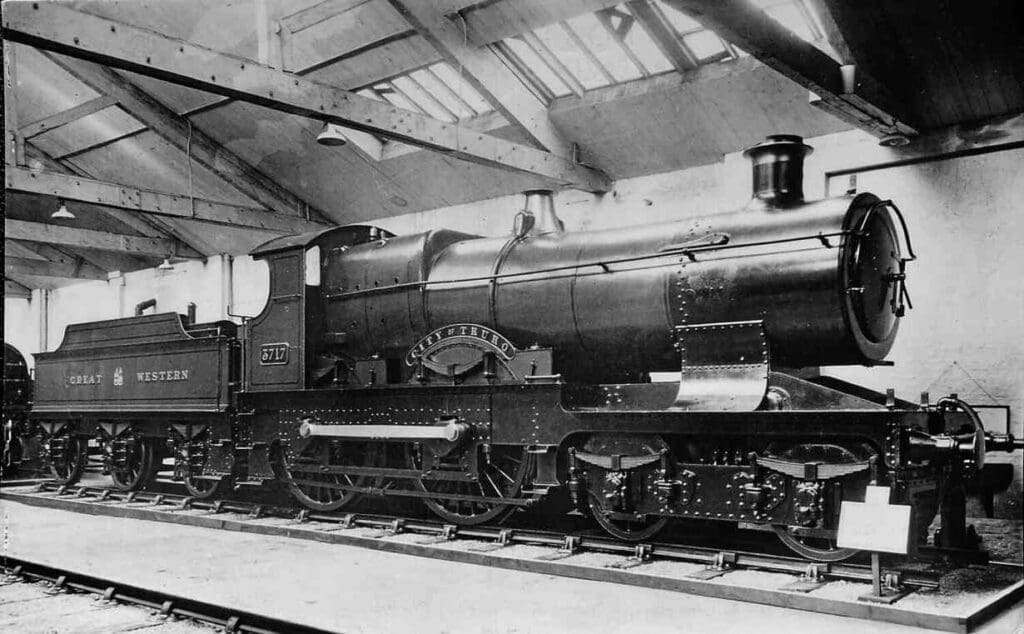

GWR 4-4-0 No. 3440 City of Truro acquired its immortality not for what it definitely achieved, but what it probably did – reportedly being the first steam locomotive in the world to reach and exceed the 100mph barrier.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

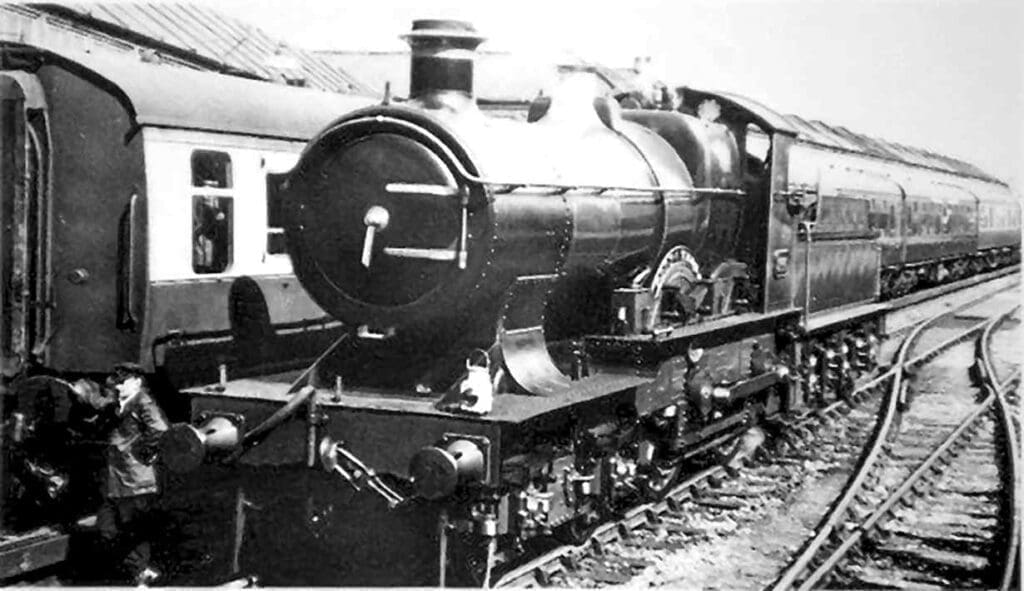

It was recorded – unofficially, but apparently with a high likely degree of accuracy – as having attained 102.3mph while descending Wellington Bank in Somerset with the ‘Ocean Mails Special’ from Plymouth to Paddington on May 9, 1904.

By rights that feat should have bestowed the 2000th locomotive to be built with instant stardom. However, because of a prevailing mood of public opinion of the day against speeding trains, City of Truro was destined to become a reluctant legend, its status very much a slow burner.

Its feat was not acknowledged by the GWR until three years later, even though a report of the 100mph run appeared in two local newspapers the following day, after William Kennedy, a mail van worker on board, conducted some unofficial timings using his stopwatch.

City of Truro (later renumbered 3717) was an example of Chief Mechanical Engineer George Jackson Churchward’s first design, the 20-strong 4-4-0 City of 3700 class, designed for hauling express passenger trains.

Ten of these locomotives were rebuilt from his predecessor William Dean’s Atbara class, the first (No. 3405) being converted in September 1902 and the rest following between 1907-9. The new 10 were built at Swindon in 1903, with City of Truro being the eighth, outshopped from the works in April 1903. All 10 were named after cities on the GWR system and were originally numbered 3433-42.

At the time, the GWR was engaged in fierce competition with its great rival in the West Country, the London & South Western Railway, to see which could bring ocean mails from Plymouth to London the fastest, and while they had not been given permission to do so, some of the Paddington empire’s drivers were determined to show what they and their Swindon-built engines could do.

On the day, it was the job of driver Moses Clements to take the train to Paddington, and by the time the train – hauling a light load of eight-wheeled postal vans with around 1300 large bags of mail on board, total weight 148 tons – had reached the South Devon banks, it appeared he had decided to “go for it”.

As the locomotive raced down the gradient from Whiteball Tunnel on the far side of Exeter, it was going faster than any member of the class had gone before.

On board the footplate was timer Charles Rous-Marten, who at around 10.45am recorded 8.8 seconds between two quarter-mile posts on the descent down Wellington Bank. If exact, this time would correspond to a speed of 102.3mph.

Sadly, the driver spotted a gang of platelayers standing on the tracks a quarter of a mile away ahead, and braked fiercely while they moved aside, carrying on into Taunton at just 80mph, ruining the recorder’s chance to confirm the speed.

Furthermore, there was no secondary timer on board to agree the claimed speed, so it was never taken as an official record.

Conscious of the need to preserve the GWR’s reputation for safety, the company at first allowed only the overall timings for the run to be published, despite the contemporary report of 100mph in the Plymouth press mentioned above.

When Rous-Marten wrote an article that appeared in The Railway Magazine a month later, he merely described the trip as setting “the record of records”.

He wrote: “It is not desirable at present to publish the actual maximum rate that was reached on this memorable occasion”, and restricted his account to reporting that the train reached the minimum of 62mph logged on the ascent of Whiteball summit.

Rous-Marten first published the maximum speed in October 1905, but he did not name the locomotive or the railway company involved.

In the Bulletin of the International Railway Congress, he wrote: “On one occasion when special experimental tests were being made with an engine having 6ft 8in coupled wheels hauling a load of about 150 tons behind the tender down a gradient of 1-in-90, I personally recorded a rate of no less than 102.3 miles an hour for a single quarter-mile, which was covered in 8.8 seconds, exactly 100 miles an hour for half a mile, which occupied 18 seconds, 96.7 miles an hour for a whole mile run in 37.2 seconds; five successive quarter-miles were run respectively in 10 seconds, 9.8 seconds, 9.4 seconds, 9.2 seconds and 8.8 seconds.

“This I have reason to believe to be the highest railway speed ever authentically recorded. I need hardly add that the observations were made with the utmost possible care, and with the advantage of previous knowledge that the experiment was to be made, consequently without the disadvantage of unpreparedness that usually attaches itself to speed observations made in a merely casual way in an ordinary passenger train.

“The performance was certainly an epoch-making one. In a previous trial with another engine of the same class, a maximum of 95.6 miles an hour was reached.”

It was only in the edition of The Railway Magazine in December 1907, nearly four years after the event, that the alleged speed of 102.3mph appeared publicly for the first time – and even then was not attributed to a particular engine. However, Rous-Marten revealed the identity on the April 1908 edition, shortly before he died.

Yet it was not until 1922 that the GWR officially confirmed City of Truro’s feat.

Then, the GWR published a letter written in June 1905 by Rous-Marten to James Inglis, the company’s general manager, giving further details of the run.

Rous-Marten had written: “What happened was this: when we topped the Whiteball Summit, we were still doing 63 miles an hour; when we emerged from the Whiteball Tunnel we had reached 80; thenceforward our velocity rapidly and steadily increased, the quarter-mile times diminishing from 11 sec. at the tunnel entrance to 10.6 sec., 10.2 sec., 10 sec., 9.8 sec., 9.4 sec., 9.2 sec., and finally to 8.8 sec., this last being equivalent to a rate of 102.3 miles an hour.

“The two quickest quarters thus occupied exactly 18 sec. for the half-mile, equal to 100 miles an hour. At this time the travelling was so curiously smooth that, but for the sound, it was difficult to believe we were moving at all.”

Doubts over the record have focused on the power of the locomotive and some contradictions in Rous-Marten’s passing times. However, his milepost timings are consistent with a speed of 100mph or just over. This sequence of eight quarter-mile timings is thought to start at milepost 173, the first after the tunnel, with the maximum speed at milepost 171.

Modern-day research has examined the evidence and used computer simulation of the locomotive performance to prove a speed of 100mph was possible – and that Rous-Marten’s timings indeed support such a speed.

So Why the Secrecy?

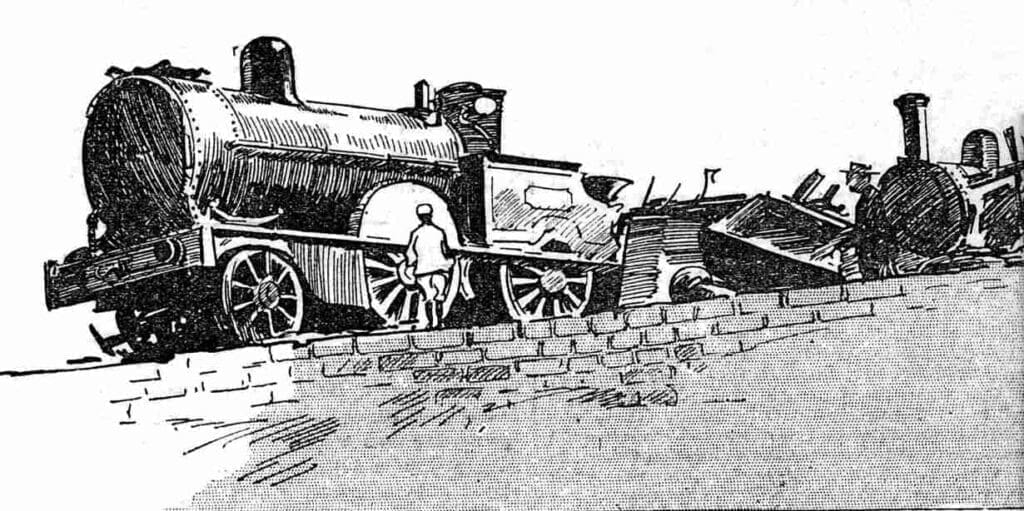

In the early hours of Monday, July 13, 1896, the 8pm Down ‘Highland Express’ from Euston to Scotland hauled by LNWR locomotives No. 2159 Shark and No. 275 Vulcan derailed at the Dock Street points to the north of Preston station in the middle of the night.

Suddenly, the whole train was ploughing its way along the track, but the drivers kept their cool and brought the train to a standstill within a distance of 80 yards.

Both locomotives and the leading coaches were badly damaged, but the train was lightly loaded and only one of its 16 passengers, a young man called Donald Mavor, was killed.

A sharp curve at the north end of the station by the goods yard had a 10mph restriction.

It was later ascertained that the express had been travelling around 40-45mph through the station. When it hit the speed restricted curve, instead of going round it the train effectively carried on in a straight line. The engines ploughed through the goods yard, with the train coming to rest just short of a bridge wall.

Overnight, there mushroomed outright hostility to what was widely seen as placing life and limb at risk for the sake of breaking speed records in pursuit of railway company prestige.

Yes, there had been far worse accidents in terms of casualty figures, but this one was different, for it marked a watershed in public opinion towards trains running at such high speeds.

In the summers of 1888 and 1895, the nation had been gripped by reports of what railway historians now term the ‘Races to the North’.

These occasions saw passenger trains from rival companies that would literally race each other to see which could reach Edinburgh from London in the quickest time over the two main trunk routes, the East and West Coast Main Lines. Driven by commercial rivalry, in 1888 the Great Northern Railway and the North Eastern Railway ran the East Coast service from King’s Cross in competition against the London & North Western Railway and Caledonian Railway from Euston on the West Coast. The supposed ‘races’ were never official, and the companies publicly denied that what happened could in any way be described as racing.

By the 1890s an East Coast route had been established further north through Scotland over the Forth and Tay bridges, allowing the North British Railway to provide a reasonably direct Edinburgh to Aberdeen service.

Accordingly, it extended the East Coast consortium’s King’s Cross to Scotland route, as the NER had running rights to Edinburgh. However, the Caledonian already had a route connecting Carlisle and Aberdeen via Stirling and Perth.

So in 1895 a second ‘race’ broke out, but this time with the added excitement of arriving at the same station in Aberdeen. Indeed, after some 500 miles from London, the two routes converged to being in sight of each other just before Kinnaber Junction, from where there was a single track to Aberdeen. The press loved it.

However, the repercussions of the Preston accident sent shockwaves through the rail industry which would hamper progress for the next four decades.

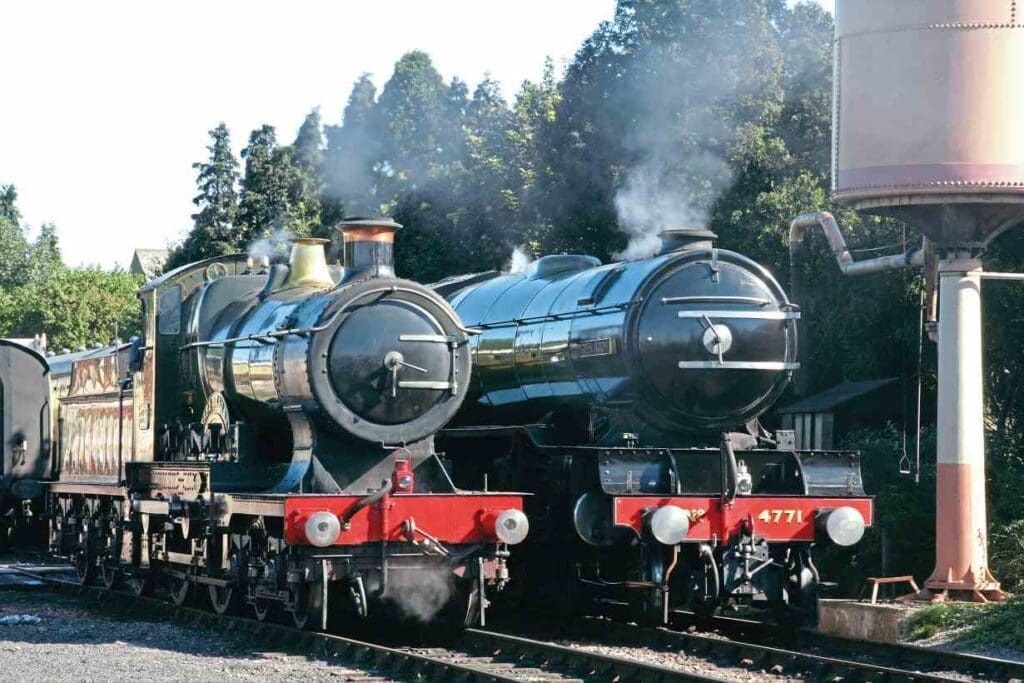

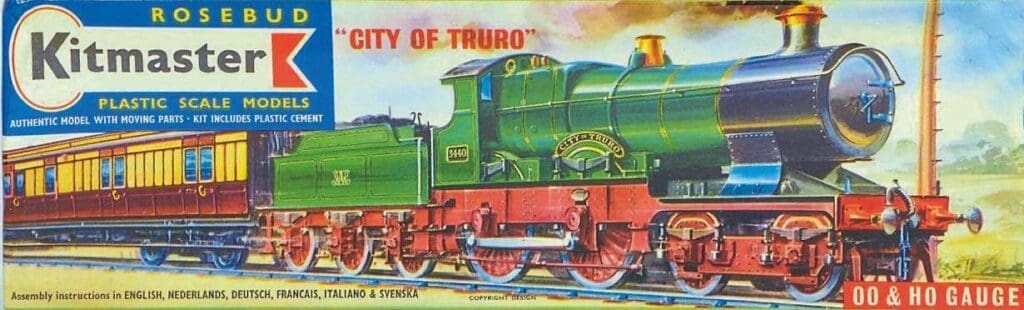

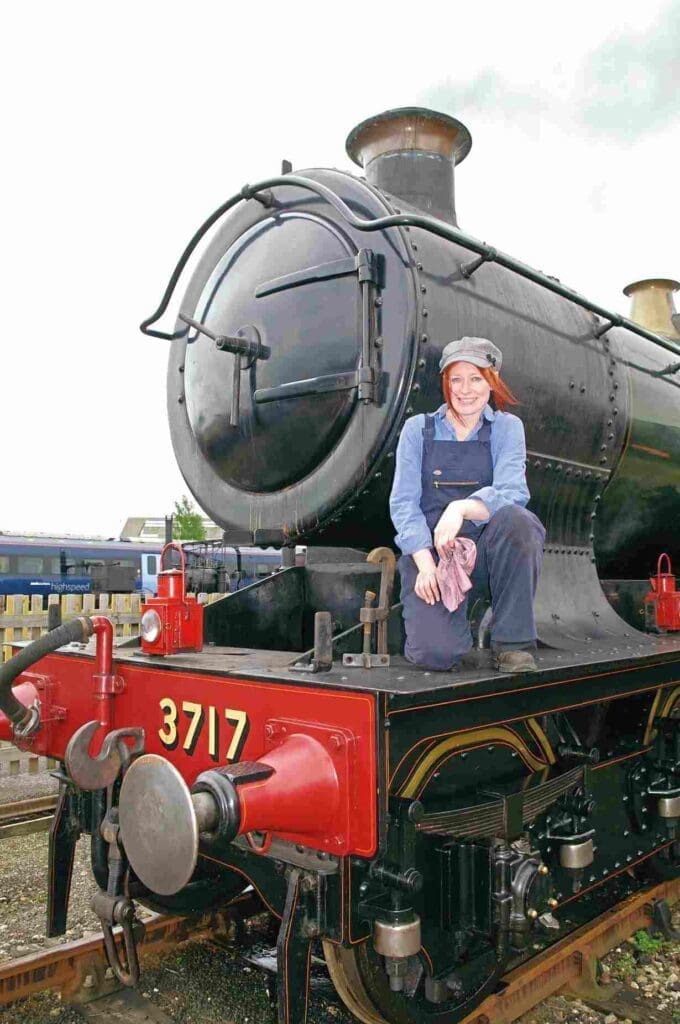

Toddington Model Launch

A new finescale OO-gauge model City of Truro was launched in early December 2009 in a bid to raise tens of thousands of pounds for the National Railway Museum. The press launch was staged at Toddington on the Gloucestershire Warwickshire Railway, on December 4, where City of Truro is based, before which the company kept details of its latest release under wraps, although rumours of its appearance appeared on website discussion forums in the days beforehand. Graham Hubbard (right), managing director of Bachmann Europe plc, presented one of the first models to the railway’s engineering director Andrew Goodman to mark the occasion. It was Andrew who had first mooted the idea of returning No. 3440 to steam nearly a decade before. After the presentation, the full-size version hauled a special train to Cheltenham Racecourse station (pictured) and back to mark the occasion.

Was City of Truro the first?

However, it seemed that despite the public reaction in the aftermath of the Preston crash, trains would still be run at very high speeds, albeit for testing purposes, but nobody broadcast the fact.

‘Truro’s’ exploit came nearly five years after a series of high-speed test runs on the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway’s Liverpool Exchange-Southport line using locomotives from John Aspinall’s newly introduced ‘High Flyer’ 4-4-2 class.

The principal express engine of the L&Y, the class had the largest boilers fitted to any British engine, but their 7ft 3in-diameter driving wheels were rare for a coupled-wheel engine.

It was reported on July 15, 1899 one such train formed by No. 1392 and five coaches, and timed to leave Liverpool Exchange at 2.51pm, was recorded as passing milepost 17 in 12.75mins, by lineside enthusiasts.

While this gives a start-to-pass speed of 80mph, given the permanent 20mph restriction at Bank Hall and the 65mph restriction at Waterloo, it has been postulated this train attained 100mph.

Sadly, the railway company never published details or timings of this trip: it is only because passing times were unofficially noted by local enthusiasts the 100mph claim is known at all.

The late David Jenkinson, former head of education and research at the National Railway Museum, and a leading expert on the LMS, which absorbed the Lancashire & Yorkshire at the Grouping of 1923, said: “It may well have been possible for an engine with driving wheels that size to achieve a feat like that on that particular route. You can probably place some credence on it.”

In his 1956 book The Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway, researcher Eric Mason wrote: “It is likely that the event will probably be regarded in the same light as the GW City of Truro run, because it is alleged no proper records were kept, and has in recent years been taken, rightly or wrongly, with a large pinch of salt.”

Another of the 4-4-2 class – No. 1417, the test engine for Hughes’ back pressure release valves – became enshrouded in “mythical legends” over its performances. Mason wrote. “Whilst there is no confirmation of an alleged 117mph near Kirkby, there is no doubt whatsoever that the engine did perform some really fast running in the capable hands of driver J Chapman of Newton Heath.

“He did all the trial work with this engine and manned her on a daily duty for many months, consisting of the 11.35am 40min express from Victoria to Liverpool, back with the 1.40pm, and then the 3.20pm semi-fast to Blackpool Central, returning home with the 6.35pm express, which was booked to run non-stop from Lytham to Salford in the comparatively easy timing of 69mins.

“The later engines so fitted, Nos. 1401, 1403, 1399 amongst them, were also very highly spoken of by drivers for their free-running qualities.”

David Jenkinson commented: “The late Eric Mason was the authority on the L&Y – if he said it, it is probably reasonably authenticated.”

It has also been conjectured that locomotive crews reached high speeds in defiance of speed restrictions, but played down the fact because of the fear of losing their jobs.

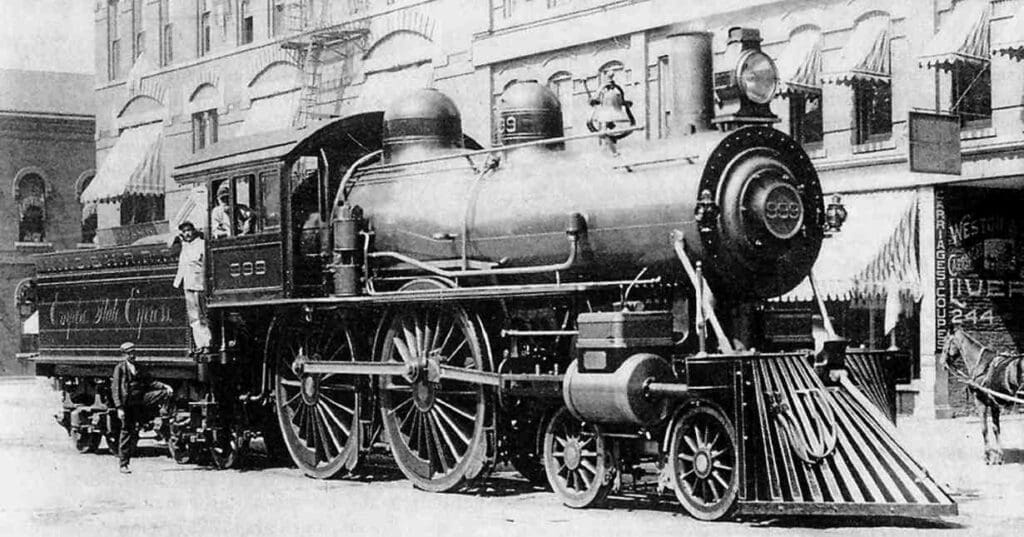

Across the Atlantic, it was claimed New York Central & Hudson River Railroad 4-4-0 No. 999, built to haul the ‘Empire State Express’, became the first in the world to travel at more than 100mph, during an exhibition run of the train on May 10, 1893, the year of its construction, although historians believe the probable maximum speed was 81mph – as recorded by observer J P Pearson, who rode on the train. Unlike City of Truro’s feat, there are no timings showing the acceleration up to 100mph. No. 999 was preserved in 1962, and is now displayed inside the main hall at the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry.

It was also claimed Pennsylvania Railroad E2 4-4-2 No. 7002 reached 127.1mph at Crestline in Ohio while hauling its 18-hour ‘Pennsylvania Special’ from New York City to Chicago on June 11, 1905.

However, locomotives did not carry speedometers at the time, and speed was calculated only by measuring time between mile markers, so the claim could not be officially substantiated.

The New York Times reported on June 14, 1905 that the claims published in the Chicago press had been exaggerated, and said the real speed was closer to 70–80mph.

No. 3440’s unofficial record was recorded before any car or aeroplane had attained such a speed. However, the year before, an AEG experimental three-phase electric railcar near Berlin had seen 130mph reached, reportedly on October 27, 1903. It set a record for electric rail vehicles that was to last for the next 51 years.

After the record

Superheating of the City class boilers was first applied to No. 3702 Halifax in June 1910, and all of the class, including City of Truro, had been fitted with superheaters by 1912.

The class were subject to the 1912 renumbering of GWR 4-4-0 locomotives. The Bulldog class was gathered together in the series 3300-3455, and other types renumbered out of that series. Accordingly, the Cities took numbers 3700-3719, previously used by Bulldogs, and City of Truro became No. 3717.

It was only in 1922, when the GWR, accepting that the public mood had changed, came out in the open about the 1904 record, and the Swindon empire’s fabled publicity department did not hesitate in making the most of it. It would be another 12 years before LNER A3 Pacific No. 4472 Flying Scotsman would set an official record of 100mph.

All members of the City class were withdrawn between October 1927 and May 1931, and were scrapped, apart from one. City of Truro, which had continued in everyday service since its star moment, was withdrawn in March 1931, but was spared the cutter’s torch because of its historical importance.

Astonishingly by today’s standards, the GWR directors refused to preserve City of Truro at the company’s expense. So GWR Chief Mechanical Engineer Charles Collett asked if it could go to the LNER’s new railway museum in York.

It was donated to the rival company for preservation, and was sent from Swindon to York on March 20, 1931.

Because York was thought to be a target for Luftwaffe bombers during the Second World War, City of Truro was moved out of the museum to the safety of the small engine shed at Sprouston station (near Kelso) on the Tweedmouth to St Boswells line in the Scottish Borders.

In 1957, City of Truro made a surprise but welcome comeback to the main line.

British Railways Western Region decided to return it running order and renumbered 3440, and based at Didcot shed, it hauled both normal revenue services and special excursion trains, mainly on the Didcot, Newbury and Southampton line. It was repainted into the ornate livery it carried at the time of its unofficial record in 1904.

No. 3440 was again withdrawn in 1961, and became part of the National Collection, set up by the British Transport Commission to preserve key historic locomotives under statutory powers. The following year, it was taken to Swindon’s former GWR Museum in Faringdon Road.

There, it was renumbered to 3717 and repainted in plain green livery with black frames.

It stayed in the museum until 1984, when it was restored for the GWR’s 150th anniversary celebrations the following year. It also visited several heritage railways.

In 1989, City of Truro visited The Netherlands for six weeks to represent the UK and the National Railway Museum in the 150th anniversary celebrations of Dutch railways. The original choice for the visit was LNER A4 Paciific No. 4468 Mallard, but it failed a boiler test.

In 1990, the locomotive appeared in the National Railway Museum on Tour, an exhibition which visited Swindon in 1990, while major repairs were being carried out to the York venue, and a temporary home needed to be found for its star exhibits.

Back On Wellington Bank 100 Years On

Following a public appeal, in 2004 City of Truro was re-steamed yet again at a cost of £130,000 to mark the centenary of its unofficial record-breaking run.

Much of the work was undertaken by Bill Parker’s Flour Mill workshop at Bream in the Forest of Dean. Retired London banker and Bodmin & Wenford railway benefactor Alan Moore stumped up the cost of overhauling the boiler at the workshop.

WR Churchward 4-4-0 No. 3440 City of Truro returned to passenger-carrying traffic in April 2004 – but was not finished in time for its official launch.

National Railway Museum head Andrew Scott officially relaunched the celebrity locomotive into traffic at Toddington station on the Gloucestershire Warwickshire Railway at a reception on Friday, April 2, and in public the following day. However, its first 21st-century revenue-earning train had been on Thursday, April 1, when it hauled a private charter for Chiltern Trains over the line comprising the railway’s pre-war LMS inspection saloon No. 45048.

No. 3440 then returned to Wellington Bank to haul a series of main line specials, but at a speed of nowhere near 100mph.

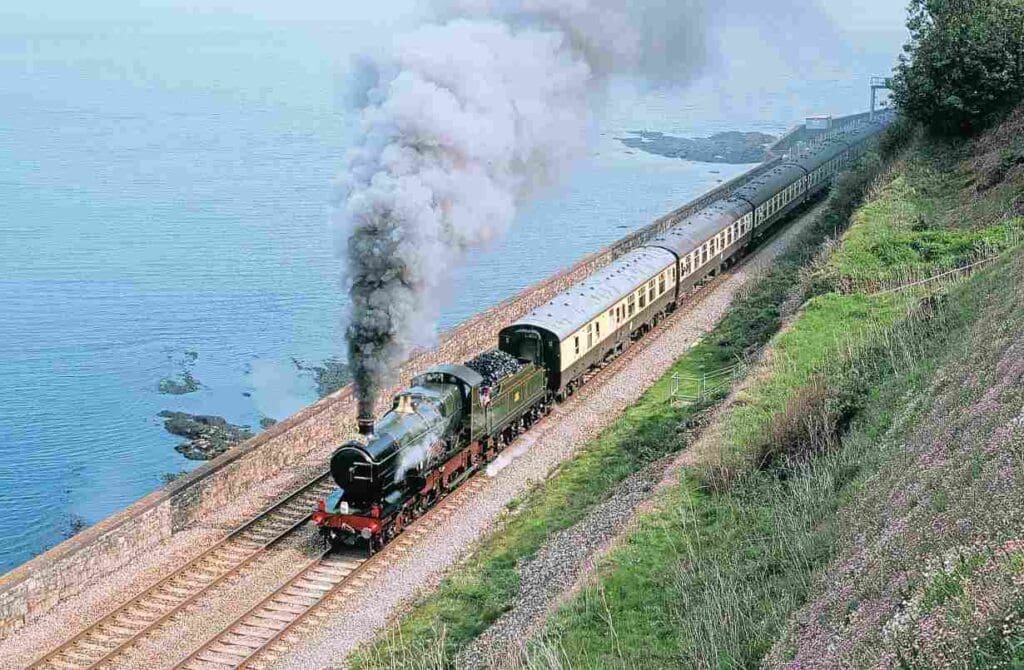

It was the legend that is City of Truro that brought tens of thousands of camera-toting spectators to line the route of the Pathfinder Tours’ ‘Ocean Mail 100’ centenary specials, headed by the overhauled 4-4-0, from Bristol Temple Meads to Kingswear on May 8 and May 10, 2004.

Inbetween, there was a stint on what is now marketed as the Dartmouth Steam Railway, hauling special trains on the actual anniversary of the reported 102.3mph run – May 9.

City of Truro successfully completed its loaded test run from Birmingham Snow Hill to Stratford-upon-Avon on Sunday, May 2, after earlier running from Tyseley Locomotive Works to Stratford and back with its support coach.

However, the engine’s support crew had experienced a few anxious moments before the 101-year-old veteran was cleared to take the first leg of its special out of Bristol Temple Meads on the Saturday. Rerailed after arriving at Barton Hill depot by low loader from Tyseley on May 6, it soon became apparent that compared to standby engine, CWR 4-6-0 No. 5029 Nunney Castle, the 4-4-0 was sitting down on its haunches. Adjustments to No. 3440’s springs lifted frames and buffers to the correct working height, while up on the footplate a speedometer fault required attention.

Historically speaking, very few of Churchward’s engines, including the 10 Cities, were fitted with speedometers, but in the modern age of paperwork and signatures for everything that moves on rails, one is judged to be critical to safety.

As a result, City of Truro was out and about early on the Saturday morning, departing at 7am for a test run to Weston-super-Mare and back to test it. The speedometer passed.

Given the ‘tip’ the 4-4-0, hauling seven coaches, 245 tons on the drawbar, got away to an excellent start, travelling down the Bristol & Exeter road to reach Taunton seven minutes early. Any hopes of attacking Wellington Bank were dispelled by a 20mph restriction through the station and for another half mile, but notwithstanding the check, No. 3440 accelerated to tackle the remainder of the 1-in-80 climb in fine style.

Once over the top, City of Truro continued to thrive, cruising at or around 60mph, and with favourable signals rolled into Exeter St David’s early. It missed out the water stop – a brave decision some might say, considering the tender tank holds only 3500 gallons.

Setting off in glorious sunshine, No. 3440 attracted enormous crowds en route. Running easily, the 4-4-0 skirted the sea wall at Dawlish, passing Newton Abbot on time to arrive at Paignton 10 minutes ahead of its booked time. Held by signals, the train still managed to reach Kingswear two minutes to the good.

On the Sunday, No. 3440 hauled two specials over the heritage line now known as the Dartmouth Steam Railway, the 11.15am and 2.15pm departures from Paignton to Kingswear and return. According to local reports, the number of passengers riding on the trains was equalled by lineside photographers!

The railway’s general manager Barry Cogar said: “It would have been nice to have celebrated the anniversary with a fast run but there’s no way we can run a 100-year-old veteran locomotive at high speed.”

Station supervisor and railway author Geoffrey Kitchenside said: “It was one of those once-in-a- lifetime occasions.”

Departing right time for the return trip back to Bristol, the engine had no difficulty in taking the seven coaches up the bank from Paignton, but sadly, the homeward run suffered from delays, affecting all traffic. Checked at Newton Abbot, the ‘Ocean Mail 100’ was pathed behind a stopper and eventually put inside at Dawlish Warren to allow two High Speed Trains to pass.

At Exeter, the heavens opened. Heavy rain, hail and thunder created a vibrant cacophony so loud it transcended the noise of trains moving in and out of St David’s. While that was happening, traffic delays produced an upstaged event worth recording. A late-running First Great Western HST pulled in alongside the ‘Ocean Mail’ special and, coming to a halt, revealed its leading power car’s nameplate: City of Truro!

Delayed again by service trains, No. 3440 departed Exeter five minutes down, but when given the road, took command, tackling the long climb up to Whitehall in positive fashion, the engine entering the tunnel at 38mph. Romping downhill, but checked to 50mph on that bank, the special steamed into Taunton ahead of time. The train departed 30 minutes early.

The engine’s run was cut short by a ‘yellow’ at Bridgwater and again at Worle Junction. By now, the train’s progress was impinging on other services so control put the special inside at Yatton, where City of Truro’s fireman had to keep his engine quiet for 15 minutes. Given a ‘green’, No. 3440 took up the challenge and succeeded, bowling into platform 4 at Temple Meads, eight minutes early.

Was it a success? “Yes”, said Pathfinder Tours’ Richard Szwejkowski. “Of a total of 560 seats available (280 per train), 507 were occupied. Naturally, the Monday’s train carried fewer passengers because of work commitments.”

City of Truro subsequently hauled several specials on the national network, although because it lacked several modern safety features it was later taken out of main line service.

Afterwards, it continued to be based for several years on the Gloucestershire Warwickshire Railway, from where it visited several heritage railways.

In 2010, it took part in the GWR 175 celebrations to mark the 175th anniversary of the company, running at the Great Western Society’s base at Didcot Railway Centre.

In 2013, the NRM withdrew City of Truro ahead of its boiler ticket expiry because of a hole being discovered in one of its tubes.

After examination it was found the locomotive required more work than first thought and was unlikely to be operational in the foreseeable future.

In late 2015, City of Truro returned to STEAM – Museum of the Great Western Railway, which occupies part of the former Swindon Works, and the following year took part in Swindon 175, celebrating 175 years since the inception of Swindon as a railway town in the era of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Daniel Gooch.

As of spring 2019, the National Railway Museum confirmed it has no plans at the present time to re-steam City of Truro.

Advert

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.