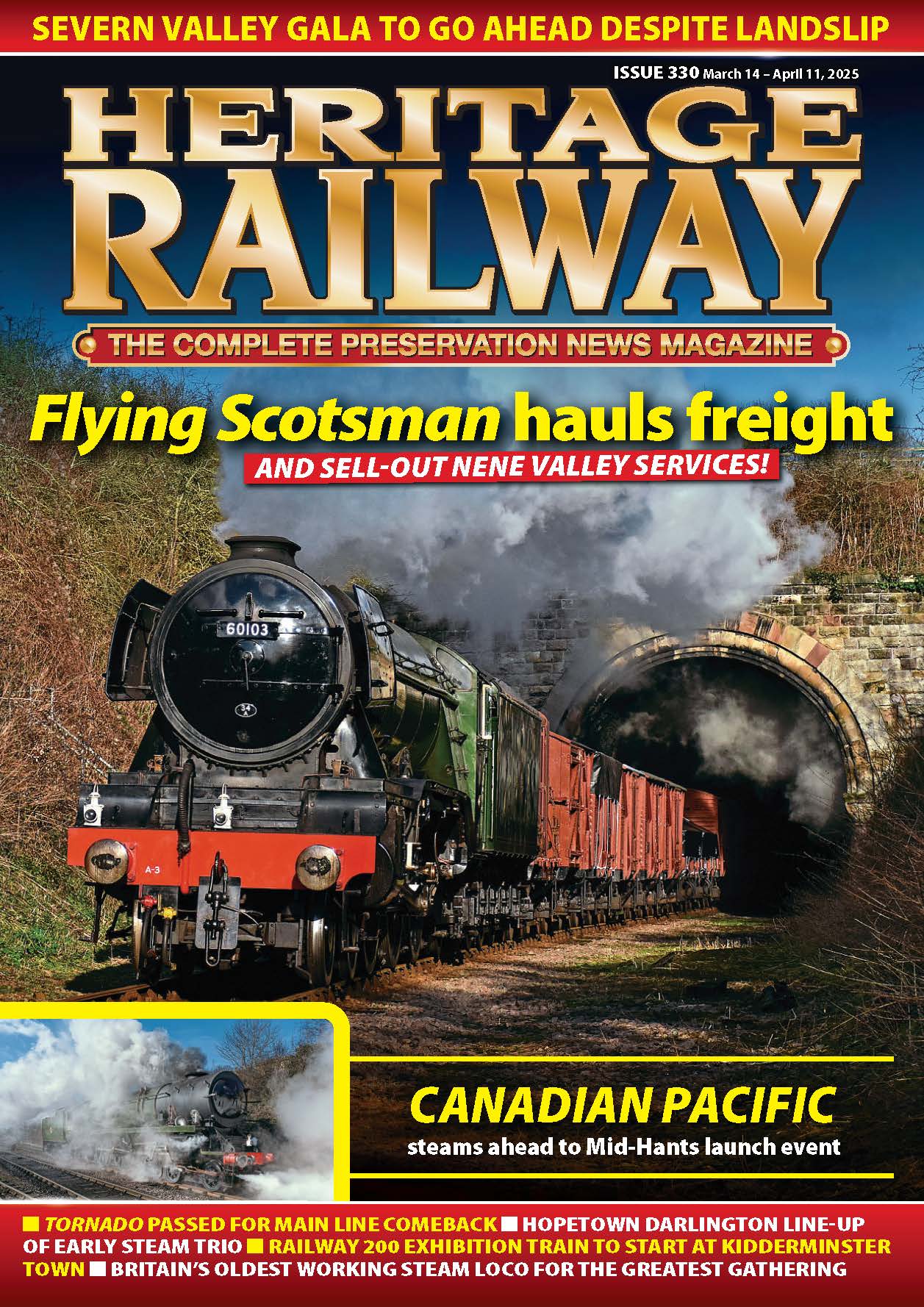

The Rosedale branch was very close to the North Yorkshire Moors line. Geoff Courtney delves into the history of a a remote railway outpost that closed down in the 1920s.

It is only a small, seemingly unimportant, line on an original, mid-1920s’ railway map that hangs in my study. Although published by the GWR – albeit printed in Edinburgh – and cleverly squeezing in every single one of that company’s stations, it extends its coverage to as far north as Perth in Scotland.

Non-GWR lines and major stations are also illustrated in a spider’s web weaving across the cloth, with important routes in thick black (GWR routes are in red) and lesser lines much thinner. One of them is a branch line to Rosedale, running off the Middlesbrough-Whitby line in the heart of the Yorkshire Moors.

Now that’s an area my wife and I have visited frequently, thanks to the irresistible attraction of the scenery, the local ale, the North Yorkshire Moors Railway, and much else. But a railway terminus at isolated Rosedale, in the sort of rugged, sparsely-populated and inhospitable terrain that would make railway engineers fearful and railway accountants and investors turn their backs? Surely not!

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

But the answer to that is in the affirmative – and not only was there a railway, but it was standard gauge, part of the LNER system in its latter days, rose to a height of more than 1000ft above sea level, and was approached by one of the steepest roads in Europe.

The reason for the railway in such a remote outpost was iron ore, which occurs in the Jurassic rocks of the region. Research by the Scarborough Archaeological Society indicates it was mined in north-east Yorkshire as far back as the early Iron Age more than 2000 years ago, and further records have been able to pinpoint the presence of a forge in Rosedale nearly 700 years ago.

With iron ore being the raw material used in the production of steel, mining in Rosedale became big business as Britain embraced the Industrial Revolution and beyond.

Workings started high up to the west of Rosedale valley in 1856, and two years later the Ingleby Ironstone & Freestone Mining Co built a three mile railway branching off the North Yorkshire and Cleveland Railway’s Picton-Grosmont line at Battersby station – at that time called Ingleby Junction – up to the company’s workings at Ingleby.

This line was standard gauge to the foot of a fearsome incline, but continued in narrow gauge up to the company’s mine near the top. Within months of the branch opening it had been purchased by the NYCR, which itself was acquired by the North Eastern Railway in January 1859, and the NER built a new standard gauge line that climbed the incline to the top.

Too steep for locomotives

At one-in-five the incline, which was

1430 yards long and ascended to a height of 1370ft above sea level at Incline Top, was too steep for locomotives, and was operated by empty wagons hauled up the slope by steel cables using the weight of descending wagons laden with iron ore.

The NER didn’t stop at Incline Top, however, but continued for 11 miles to a terminus at Bank Top above the village of Rosedale Abbey nestled below in the valley. This extension opened in March 1861, an astonishingly short timescale considering the unfriendly terrain and adverse weather the railway’s engineers would have encountered.

In 1865 the Rosedale railway system was expanded by the NER with the opening of a line that branched off the Bank Top line at Blakey and ran for nearly five miles to mines on the opposite, eastern side of the valley.

By this time the Rosedale area was becoming a hive of activity, with ironstone production increasing from nearly 80,000 tons in 1861 to more than 233,000 tons in 1866 – when the east mines came into operation – and then to a massive peak of 560,000 tons in 1873. This naturally led to a population explosion that saw 2839 people living in the area in 1871, a near four-fold increase from the 784 a decade earlier.

Transformed

Between them, the North Eastern Railway and the mining companies transformed what was previously a deeply rural environment into a region offering employment, accommodation – most railway workers were housed with their families in terraced cottages close to the line – schooling, three Methodist chapels, a lecture hall, reading rooms and shops. There was even a surgeon, employed to attend to injuries caused by roof falls in the mines or moving wagons on the railway.

Inevitably, Ingleby Incline was the most dangerous location on the railway, with accidents caused by wagons breaking loose from the cables and plunging down the precipitous gradient being common. The scenario is illustrated by a leaflet on the railway published by Rosedale History Society, which states: “The whole system was remotely controlled by two men from a brake cabin located at the top of the incline, with good views both down the incline and back towards the drum house.

“There were frequent accidents with wagons disconnecting from the cables. In clear weather operation was controlled visually, but often cloud, rain squalls and mist obstructed the view, and the control was assisted by bell systems and latterly by telephone.

“There were railway employees housed at the top and bottom of the incline.

“At the top there were four houses, and the conditions there were so severe that this outpost was known as ‘Siberia.’ People were not supposed to ride wagons on the incline, but this was often ignored.”

In its early years the railway was operated by NER 93 class 0-6-0 double-frame tender locomotives, Nos. 422/3 built by Robert Stephenson & Co in 1860 and Nos. 564/8/9/71, built by R & W Hawthorn in 1866. To give a scale to the railway’s operation, the company had also purchased no fewer than 200 eight-ton hopper wagons with wooden frames and metal bodies, enabling them to be loaded with hot ore directly from the kilns. Untreated ore was carried in wooden wagons.

A two-road engine shed was built at Rosedale Bank Top in 1861 – dare we call it ‘Top Shed’? – and here the locomotives working between Incline Top and the Rosedale terminus would remain for several years, due to the difficulties of moving them down the incline, an operation that required the removal of the centre coupled wheels.

The 93 class locomotives were replaced by Class 1001 long-boilered 0-6-0s, of which 13 were known to have operated on the line, including examples built by Hopkins Gilkes & Co of Middlesbrough and Avonside Engine Co of Bristol. These locos, built between 1856-75, were of a robust design, as they needed to be in a fierce environment that was typified by a 3½ month snow blockage in the winter of 1894/95 and another lasting for five weeks in 1916/17.

Stayed to the end

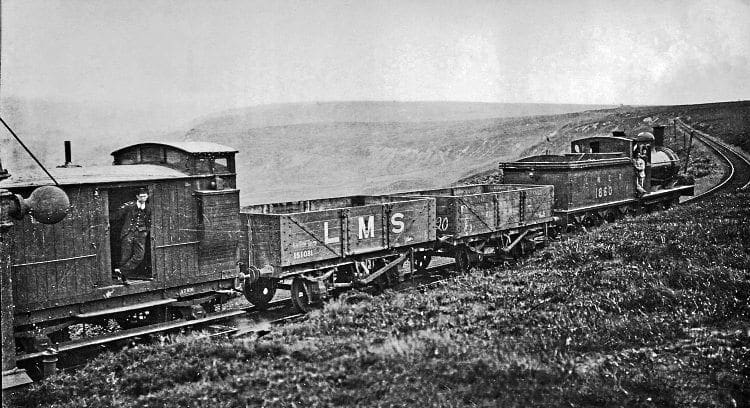

After the end of the Great War traffic declined due to increased costs and the falling price of iron, and by 1921 the fleet of Class 1001s had given way to just three replacements – NER Wilson Worsdell-designed Class P 0-6-0

Nos. 1860, 1893 and 1950, all of which had been built at Gateshead or Darlington in 1900.

These stayed to the end, which came in June 1929, when operations ceased and the railway, which had been inherited by the LNER in 1923, closed with the departure of No. 1893.

Nos. 1893 and 1950 remained in LNER traffic as Class J24 until 1938 and 1945 respectively, but No. 1860 outlasted them both, surviving into BR ownership and being withdrawn as

No. 65619 from York (50A) in November 1951.

The Rosedale engine shed was demolished in 1937 and its stones used to build the village hall in Hutton-le-Hole four miles away. Down at the other end of the railway, Ingleby Junction – which was renamed Battersby Junction in 1878 and simply Battersby in 1893 – was the location of another engine depot, a three-road shed which provided locos working the line to the foot of Ingleby Incline.

This had an even shorter working life than its Rosedale counterpart, having been opened in 1875 but closed 20 years later, although it wasn’t demolished until 1965 due to its post-railway use as a store and rifle range.

Seemingly against all the odds, the station of Battersby remains opens to this day, on the Middlesbrough-Whitby line which passes the North Yorkshire Moors Railway at Grosmont.

In engineering terms, the Rosedale Railway may not have been up there with such lines as the Settle-Carlisle or Midland Railway Peak District routes – it was, after all, only 14¼ miles long, plus a further 4¾ miles from Blakey Junction to the east mines, crossed just four minor roads, and had only one bridge – but its building was still a remarkable achievement.

In today’s age of suffocating red tape, nervous caution and endless debate and introspection, it is difficult to comprehend that the standard gauge stretch from the foot of the Ingleby Incline to Rosedale Bank Top was completed in less than two years, with none of the tools available today and in conditions which, at times, must have tested everyone’s physical and mental state to their limits.

It is also a tale of hardship, Victorian ingenuity, loyalty – one engine driver, Jacob Baker, spent 51 years of his service at Rosedale, retiring in 1919 – and a steely determination to face head-on, and overcome, adversity.

Advert

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.