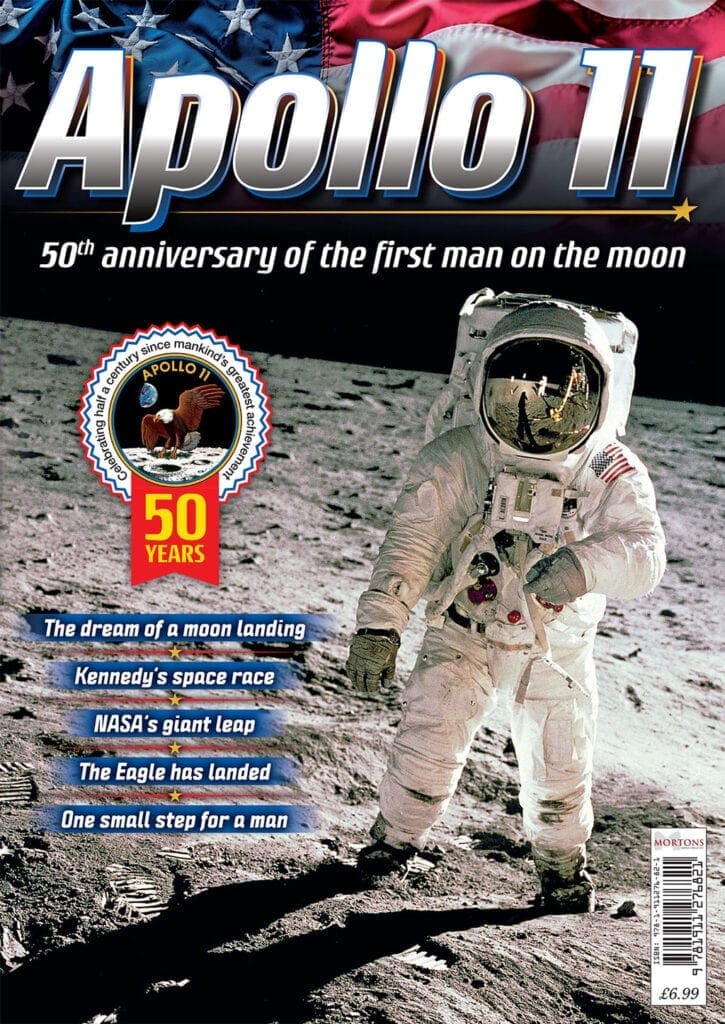

This Thursday (16/07/20) marks the 51st anniversary of the Moon landing and AllMyReads has the perfect book to discover the story behind one of the most important events in space exploration. Check out this preview from the fantastic bookazine, Apollo 11.

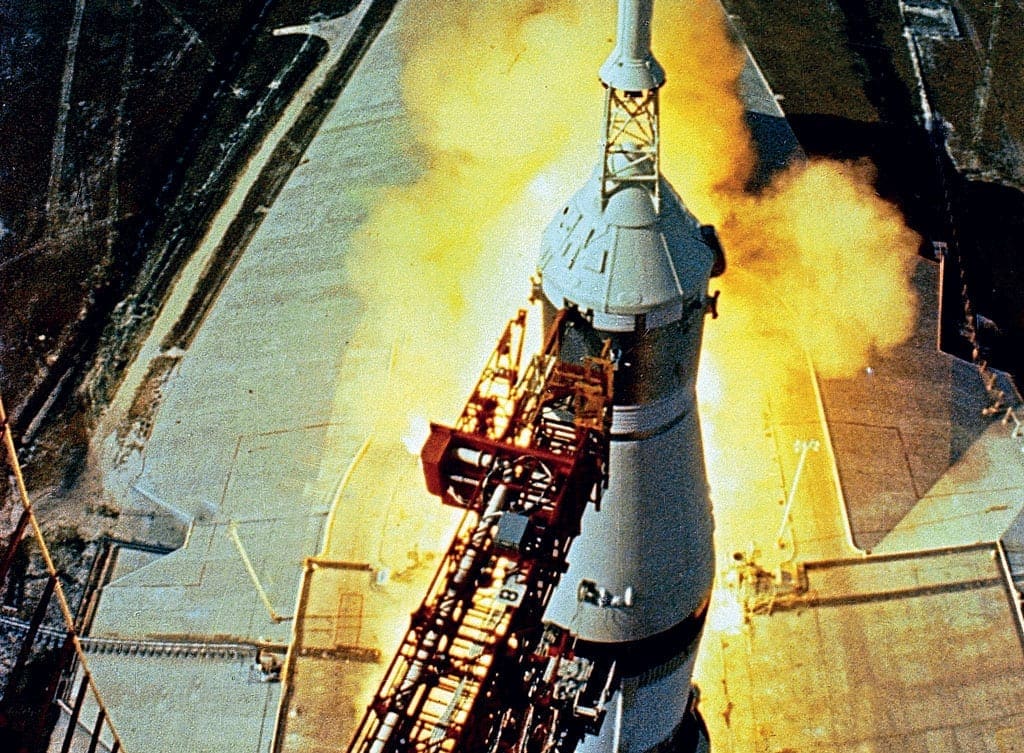

Lift-off occurred at 9.32am local time, 8.32am in Houston or 1.32pm universal time (GMT) and 2.32pm in London, the moment the mission clock started from when all events would proceed according to an elapsed duration from that moment.

The official tally on those who witnessed it with their own eyes totalled 3500 news people (a third from 55 overseas countries), the former President Lyndon Johnson, the Vice President Spiro Agnew, four cabinet members, 200 Congressmen and women, 60 ambassadors, 40 mayors and 19 state governors. President Nixon preferred to remain in the White House along with astronaut Frank Borman who served as liaison.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

The ride up into orbit was a typical Saturn V flight. As Mike Collins would recall: “This beast is best felt. Shake, rattle and roll! We were thrown left and right against our straps in spasmodic little jerks. It is steering like crazy, like a nervous driver of a wide car down a narrow alley, and I just hope it knows where it’s going, because for the first 10 seconds we are perilously close to that umbilical tower.”

The inboard engine on the first stage cut off at two minutes 15 seconds, the outer four burning until two minutes 42 seconds before the S-IC immediately separated, the second stage ignited one second later, the adapter ring was jettisoned at three minutes 12 seconds followed by the launch escape tower at three minutes 18 seconds.

The ride on the cryogenic S-II was smoother and quieter than it had been on the kerosene-fuelled first stage. A shift in the mixture ratio between the hydrogen and oxygen propellants brought a slight reduction in acceleration, helping even out the propellant consumption versus energy obtained from combustion.

The S-II burned for almost five minutes before the centre J-2 was shut down at seven minutes 41 seconds followed by the remaining outer four engines at nine minutes eight seconds, the total lift on the second stage lasting six minutes 27 seconds.

By this time the remaining stack was in space and travelling horizontal to the Earth’s surface below, the third stage now required to provide speed rather than altitude. Ignition of the single J-2 engine on the S-IVB stage occurred at the instant of separation, one second after the S-II shut down and it continued to burn for two minutes 31 seconds.

Notionally registered as occurring 10 seconds later, orbit insertion placed the docked assembly in a slightly elliptical orbit of 116 miles (186km) by 114 miles (183km).

In an outstanding display of precision, the velocity of the now much reduced stack was, at 17,431.5mph (28,047km/h), within 1.1mph (1.7km/h) of the pre-planned value! For the next two revolutions of the Earth, Apollo 11 coasted toward the appropriate point on the opposite side of the Earth to the place in space the Moon would be when the spacecraft arrived nearly three days later.

As Apollos 8 and 10 before it, Apollo 11 would be placed on a trans-lunar trajectory which, but for the presence of the Moon, would be a highly elliptical orbit of the Earth. Instead, at almost the apogee of that orbit, it would be seized by the gravitational presence of the Moon, sweeping around in its orbit to meet the docked space vehicles coming up from Earth, pulling it to itself as the two objects converged.

When the TLI burn came at two hours 44 minutes 16 seconds elapsed time, the S-IVB stage fired its J-2 engine for five minutes 47 seconds, propelling the stack to a speed of 24,250mph (39,018km/h). From that instant, Earth’s gravity began to pull on the mass hurtling away from the planet, slowing it at an alarming but diminishing rate as the distance increased.

Next order of business was to separate from the S-IVB, turn around, move back in, dock with Eagle and extract it from the spent rocket stage. Separation occurred at three hours 17 minutes five seconds, the spacecraft having already slowed to 16,675mph (26,830km/h).

Later, Buzz Aldrin would relate: “Eagle by now was exposed; its four enclosing panels had automatically come off and were drifting away. This of course was a critical manoeuvre in the flight plan. If the separation and docking did not work, we would return to Earth. There was also the possibility of an in-space collision and the subsequent decompression of our cabin, so we were still in our spacesuits…”

Slowly, the Apollo spacecraft was turned around and moved in to dock nose-on to the upper docking collar of the Lunar Module, establishing Columbia and Eagle locked together as a single structure. Twelve latches fired in ripple-fashion with loud ‘clunks’ like gunshots as they snapped closed at three hours 24 minutes three seconds, the combination having slowed now to 15,450mph (24,860km/h).

Then, 43 minutes later, Eagle was unlatched from the adapter ring at the top of the S-IVB and the docked spacecraft were clear, speed now down to 10,950mph (17,618km/h). Incredibly, less than 90 minutes since the TLI burn, the Earth had stripped 55% from the speed of Apollo 11. Curving round the planet but getting farther away with every minute, Apollo 11 was now 13,500 miles (21,700km) from Earth…

You can find out everything about the historic mission to land the very first man on the moon in the brand new Apollo 11 bookazine.

Advert

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.