Working on the footplate is often regarded as having been glamorous, especially as a driver. Brian Bell tells what it was like as a fireman, keeping the coal flowing towards the metropolis in the 1950s.

Monday, January 26, 1959. Driver R (Dick) Peart. New England shed. Booking on duty at 2.30am on a cold, windy winter’s morning to work a New England – Mansfield train of coal empties was not quite the best way to start the working week, especially after only a few hours’ sleep.

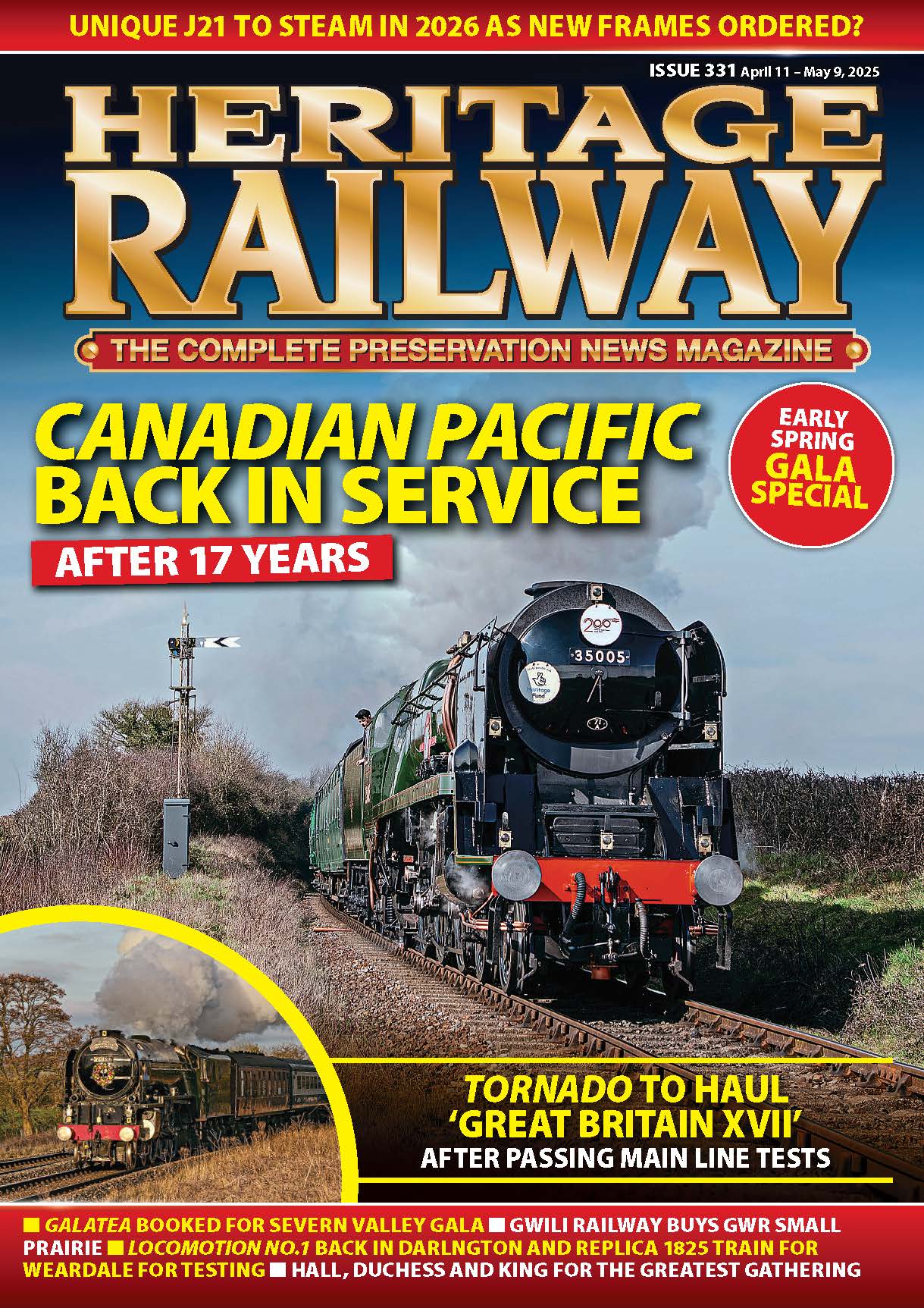

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

This was a rostered ‘change over’ diagram working, (Working Timetable train No. 334) with the prospect of a long 10 or 11-hour shift. The dreaded thought that you would have to repeat the sequence for the next five days did not really enthuse when you were roused at 1.30am.

‘Change over’ diagram working was a system whereby a freight train destined from A (in this case a New England coal empties) to B (Mansfield) and another in the opposite direction from B to A, (coal train from Mansfield Colliery to New England) departed at about the same time and were booked to meet somewhere in-between.

The exact place where engine crew and guard changed over and worked back to their home depot depended on how each train ran to time and the precise location Train Control decided

was appropriate.

It should be pointed out that in pre-Second World War times it was the accepted practice that most engine crews worked a train throughout to its destination, then lodged overnight and worked home the next day.

Some larger depots, such as Immingham, even had purpose-built dormitories, but most lodgings took place in private houses, some of which left quite a bit to be desired, as I was regularly informed (i.e. climbing into a bed someone had just risen from!).

Archaic system

Following the end of the war the unions demanded an end to this archaic system and the railway companies then decided to bring in the more acceptable ‘change over’ system, especially for slow heavy freight duties, with the advantage of enginemen being rostered to cover freight workings within an eight-hour shift.

However, during the 1950/60s period the majority of freight trains were still being operated loose-coupled and classified as ‘unbraked’; coal trains especially, with the effect that few, if any, of these workings ever finished within the eight hours rostered working. (Unbraked meant that only the engine and guards van at the rear had brakes to control the train).

Overtime working during this period of time was rampant and it would be fair to say that quite a number of drivers knew just how to work it to their own and the fireman’s financial advantage. (For instance, after passing a distant signal at caution, the golden rule was to never look back to see if it was pulled ‘off’ i.e. clear to proceed through the next section.

That way it meant slowing down and being prepared to stop at the next ‘stop’ signal, obviously causing a delay and having to pick up speed again). However, you always tried to finish within 12 hours as rules were laid down that you were required to have 12 hours of rest before resuming work again. It was essential for obvious reasons that you didn’t miss a lucrative rostered weekly working.

To cover certain long distance workings (main line expresses and ‘Class C’ express freight trains), some depots volunteered to have a ‘lodge’ link. These rostered workings were highly sought-after by some depots and crews, due to the very high mileage payments. (e.g. Kings Cross – York and Newcastle depots), plus having the top Pacifics to work on. Mileage payments were calculated at 140 miles, which equalled an eight-hour shift as a day’s work, plus every additional 15 miles was paid at one hour’s additional pay.

In the 1950s, despite an increase in the use of oil, coal was still the main source of energy throughout the whole of Britain, used primarily in generating electricity; converting into coal gas; providing power for industry, and predominantly for domestic cooking and heating.

With the bulk of the country’s main coalfields situated in Yorkshire and the East Midlands it was a massive transportation problem to transfer thousands of tons of coal daily to a power-hungry London and the South East.

Rail was obviously the main method with one route via the old Lancashire Derbyshire & East Coast line to Lincoln, then along the Great Northern through Boston and on to Peterborough, where thousands of coal wagons would be shunted and reformed, before making their laborious way down to Ferme Park in London, via the East Coast Main Line.

The other East Coast route was also via Lincoln, but down the Great Northern/Great Eastern Joint to Sleaford, then on to Spalding and March, where again trains were reformed at the massive freight yard at Whitemoor before being transferred to London via the GE.

Congested rail routes

The old Great Central route to the port of Immingham, originally designed for coal shipment, was also widely used. Thousands of tons of coal were transported daily by rail to the port, then loaded onto large bulk carriers that steamed south down the East Coast and in to the River Thames, thereby avoiding the congested rail routes into London.

All coal trains ran under the class H heading but when returning as coal empties, they worked under the slightly faster-timed class F; both classes of trains being operated loose-coupled and unbraked. These workings were all rostered as ‘change overs’ with the change over point on the originating LDECR area trains, usually at Bardney, which is just south of Lincoln.

On New England – Ferme Park workings it would normally be at Hitchin, where trains could wait on the ‘Up’ and ‘Down’ slow lines while taking water. However, some diagram workings involved working all the way through to Ferme Park, a journey taking up to six and even eight hours after which crews travelled home ‘on the cushions’ (on the next available passenger train).

Some rostered diagrams worked in reverse, whereby a crew would travel to Ferme Park and work a coal empties back to New England. At that time the Up and Down slow tunnels at Potters Bar were in the process of being constructed, thereby all slow freight traffic destined for the large marshalling yards at Hornsey were routed via the so called ‘New Line’.

This branched off the ECML just south of Stevenage then via Hertford, rejoining the ECML at the massive rail complex at Wood Green, thereby avoiding the mass of commuter trains operating on the main line.

Loose-coupled freight trains were the main method of freight train operation for nearly 100 years, right up to the 1960s and the end of steam power. Loose-coupled meant that each wagon was coupled up to the next with a three-link steel coupling, which gave a gap of around six to eight inches.

This had the effect that when a driver applied power from stationary, he managed to pick up the weight of each wagon one by one rather than moving the whole train weighing around 500 to 600 tons dead weight in one go. Obviously, this relied totally on the skill of the driver; move off too quickly and the poor old guard sat in his van at the rear could be thrown to the floor.

Equally, when running downhill the driver would shut off steam and freewheel; the weight of the train gradually pushing the engine, but when at the bottom and beginning the next climb, it required expert judgement as to when to gradually apply steam and pick up the weight of each wagon. Applying too soon could cause a violent snatch and the possibility of snapping a coupling and the train parting. Believe me, guards on such trains certainly had a rough ride with some drivers!

With the introduction of the BR Standard 9F 2-10-0 and the development of 16-ton ‘fitted’ (vacuum-braked) coal wagons, it was decided to run express freight class C (fully brake-fitted) coal trains of 35 wagons maximum up the main line to Ferme Park. All these trains operated during the night when the main line was not so busy with a booked timing of three hours.

On arrival at Ferme Park the engine ran light to Hornsey shed where it would be watered then coaled at the automatic coaling plant (if the driver dared sneak past the running foreman) otherwise the fireman had to shovel coal forward in the tender.

The crew then took refreshments before returning back to Ferme Park to work a class ‘C’ coal empties back to New England, all within eight hours. I was in No. 4 link where most of these workings were rostered and I know from personal experience that it was an exceptionally long hard day’s work. (150 miles total meant just one hour’s extra overtime).

However I digress; back to the morning of January 26 and first the ritual of preparing your own engine. Today we were in luck; it was a Langwith O1 2-8-0 No. 63703; a Thompson rebuild of a GCR O4 with a B1 boiler, modern cab and bucket seats! It was nowhere near as good a steamer or ride as the original Robinson-designed engine, but on a winter’s day the modern cab with sliding windows afforded considerable protection from a cold wind. (At least Thompson did think about the crews’ comfort, pity about his locomotive alterations or design).

Allowed one hour

Crews were allowed one hour to prepare an engine (oil, retool, bring up to normal working steam pressure and test everything) and it wasn’t long before we were running light engine tender-first to the massive Westwood sidings, where we coupled up to our train of around 50-60 empty coal wagons.

O1s were always top side of the job and it didn’t require much effort to get underway, passing slowly along the ‘Down goods’ line between the New England depot on one side and the rows of grimy terraced railway houses (the Barracks) on the other.

After passing under the Midland & Great Northern overbridge onto the ‘Down slow’, the gradient was slightly downhill to Werrington Junction and at this early time of the morning and not being required to cross the East Coast Main Line you were usually signalled direct onto the East Lincolnshire main line.

Thereon to Spalding and Boston, the line passed through the very flat, featureless landscape of south Lincolnshire, but it was easy running and once a train was up to speed (around 35mph), on class F it was relatively easy to maintain it.

The 30-odd mile stretch of line to Boston was dead straight virtually mile after mile, but once through Boston it ran practically parallel to the River Witham, following each curve in the river for the next 30 miles to Lincoln. It was remarkable how on a very windy day, as the railway line followed a curve in the river, the wind would catch the empty wagons and hold the train back.

The driver would respond by either opening the regulator a little or notch down a turn on the reversing handle. Through experience the engine crew would exchange knowing glances as the train momentarily slowed down, acknowledging the fact: “It’s a train load of wind again.”

One of the interesting aspects working over this section, especially during the early summer light mornings, was the vast number of anglers on the riverbank, for virtually the whole length of the river.

This vast number were ‘Sheffielders’ who worshipped fresh fish angling and practically all gave a cheery wave as you passed by. Another fact was that due to the desolation of the line, during early summertime, BR ran ‘fishing special’ trains from Sheffield and allowed passengers to alight in between sections to reach their angling stations – most unusual, but at least one method of earning some extra revenue! Strangely, for the numerous times I passed by, I never saw anyone catch anything.

Signal at caution

Approaching Bardney you would be hoping to observe the distant signal winking green in the darkness ahead, indicating right through and on to Lincoln, because either your ‘change over’ was running late or cancelled.

This meant relief at Lincoln and home ‘on the cushions’. Normally, as it was on this occasion, the signal would be at caution and as the driver gradually brought the train’s speed down, ready to stop at the home signal, it was obvious from the smoke and steam ahead that your ‘change over’ was already awaiting your arrival.

The usual procedure was for the signalman to bring the train virtually to a halt at his home signal, then pull the signal ‘off’ so that the train would slowly roll past his ‘box, whereby he would slide open the window and shout “change over.”

This was an opportune moment, if possible, for the fireman to jump off the engine; cross over to the ‘box and brew a fresh can of tea from a kettle that was always on the boil for that purpose. Speed was of the essence when changing over.

As the engine slowly ground to a halt, adjacent cab to cab, the crews would change over, passing brief comments as to the train load and how the engines were performing. Today we had another Langwith O4; No. 63707, an original one of its class built in 1911, unfortunately although still a superb steamer and smooth-riding engine, the wide open ‘D’-shaped cab did not afford much protection to the crew on a cold winter’s day.

This type of locomotive had what was called the original vacuum-type injectors for topping the boiler up with water, which took a great deal of experience to operate as you had to create a vacuum in the delivery pipe to raise the feed water into the injector.

Unfortunately, as your water level dropped in the tender, the delivery pipe fitted to the boiler faceplate became warm and a vacuum became difficult to create. This involved numerous methods of attempting to cool it, especially if the boiler water level began to drop dangerously low. But we always survived, just.

Immediately I climbed back on board with a fresh brew of tea, my first concern was to check the condition of the fire. GCR O4s, being good steamers, rarely had problems, unlike the WD Austerity 2-8-0s, where the fire soon built up clinker on the firebars.

Within a few seconds you were both slowly on your way, having also given the guards the chance to change over and this was an opportune moment to build up the fire. The coal on these engines was usually of poor quality, mostly ‘ovoid’ briquettes and a mixture of coal and wet coal dust.

The reason to build up a big fire, if possible, was to give you the chance to try and eat your ‘snap’; usually sandwiches and a cake packed into a large Oxo tin. (Snap was the local name for your ‘pack-up’ but locomen from other areas called it odd names such as ‘bait’ (Sheffield men) or even ‘hockey’ (Geordies). Sandwich boxes were unheard of in those days and bread with black finger print marks didn’t seem to affect your constitution.

At least you had a fresh brew to drink, although some drivers carried a bottle of cold tea all the time. Normally you would place your white enamel tea can on a tray on the boiler front to keep warm but you had to beware that the boiler water from a leaking regulator gland directly above did not drip into it (that was an acquired taste!).

As the train slowly got under way you would look to the rear of the train while waiting to observe the green flashing light being waved by the guard indicating he was safely on board. Then with a sharp blast of the engine whistle in acknowledgement, and a nod to the driver, you began the long journey back home, trying to eat your ‘snap’ in the best way possible.

Firing a GCR O4 was totally different to the style required with the previous Thompson O1 rebuild with a B1 boiler. The O1s had an oval (GN) shaped firehole door that was lower and it required considerable skill, especially when a smokeplate was fitted, to throw coal to the front of the long firebox, whereas the GC engine had a Belpaire-type firebox with a much higher ‘O’-shaped firehole door.

These fireboxes were smaller in length but were much deeper and required a more upright stance to fire; the usual method being to build up a good fire under the firehole door and feed the front end sparingly.

Driving experience

I wasn’t the only person to describe my mate Dick Peart as an eccentric person, but one exceptionally good point he had was that once he was satisfied with your competence and knowledge of the road, he was always prepared to share the driving with you, especially as practically the whole journey home was relatively flat.

I loved driving and enjoyed the skill required to drive a loose-coupled train and give the poor old guard behind a smooth ride. To be honest some drivers had no consideration for the guard, I’m sorry to say, Dick especially, and they were well known by the ‘guard fraternity’ as very rough drivers to be wary of.

I knew this from personal experience having had to ride on numerous occasions in a guard’s van, when required by ‘Control’, as the only way to travel out or return to your home depot.

It was part of the long apprenticeship to driver status that drivers allowed senior firemen to drive to gain experience, but unfortunately it was not a compulsory company policy, just a matter for your driver.

It was therefore possible that some firemen due to be passed out as ‘passed firemen’ had very little driving experience, made worse by the fact that there was no other practical ‘hands-on’ training. One of my regular drivers later on was one of the best drivers you could be with as a mate and as an engineman; someone who took immense pride in his skill and profession, but he would never allow you to drive under any circumstance except on the shed.

Fortunately, I must say that Dick, on the other hand, when he realised that the engine was in good fettle, would just say “fill her up” (the firebox) then cross over to my side, allowing me to take over.

One important skill required by a driver was ‘road knowledge’; that is knowing the exact location of every signal and gradient, especially when driving loose-coupled/unbraked freight trains.

Bringing heavy coal trains under total control and being able to stop in the exact place required a great deal of forward planning, particularly when approaching a distant signal. Block sections could vary in length but those in the open country could be up to five or six miles between signalboxes so that when a distant signal was in the ‘off’ position, it meant a train was clear to proceed at the maximum permissible speed to the next section.

However, when running on a downhill gradient extra caution had to be exercised.

This meant bringing the train under complete control so that if the next block section distant was at caution the driver needed to be confident that if the next home signal was showing ‘stop’ he had ample space to bring the train to a halt. The driver had not only to assess the gradient but also the weight of the train, the state of the track due to weather conditions and the engine’s braking capability.

Rather implausible

To a layman, describing the situation that a train was not under complete control seems rather implausible, especially under the present strict health & safety rules, but where the running of loose-coupled freight trains 60 years ago was concerned, this regrettably was a fact.

Many a train failed to stop at adverse signals despite various methods employed by the driver, even putting the locomotive into reverse gear. Fortunately though, at main line junctions, there were in-built safety limits between additional ‘home’ – ‘inner home’ – ‘starter’ and ‘advance starter’ stop signals, and collisions were rare.

With Dick situated snugly alongside the boiler on the fireman’s side of the cab, it was left for me to sit and face the elements, but once the train was running at a pleasant cruising speed, I could stand up in the corner and observe the view ahead through the large front-facing cab window.

Fortunately, the whole of this run through the Fens of south Lincolnshire was virtually dead flat and it was relatively easy to maintain control of the train, obviously as long as you knew what you were doing.

Approaching Boston though it was a case of sitting down at the controls and simply facing the elements, whatever they threw at you.

By this time in the morning, Boston, being an important rail junction, was becoming busy and progress was regularly impeded, involving a slow crawl, but once in open country you could open the engine up again.

Some 16 miles further on the same situation would occur as the train threaded itself through a busy Spalding. Very often you would be held up on one of the Up goods lines as you watched a number of the East Anglian boat trains going through in both directions, hauled by a variety of LNER B17 4-6-0s.

Once clear of Spalding you could open up the regulator for the final 16-mile lap to Werrington Junction and set the reverser at about 15% cut-off to maintain a reasonable speed.

The vast majority of the older heavy freight locomotives had no modern facilities, speedometers etc and a driver relied on his experience and especially his hearing to judge speed. I was always curious to know how the rail authorities could honestly expect drivers to judge speed limits of 8-10 and 15mph.

Noticeboards were located, with all the numerous speed restrictions you were supposed to comply with, especially at the approach to large station complexes such as King’s Cross. Fortunately, there were no speed cameras to tell.

Finally, after negotiating Werrington, the greatest delays would be in the approach to New England, four miles further on, where under ‘permissive block’ working you could be in a long queue of freight trains, one behind the other, waiting to enter the vast Westwood marshalling yards.

To explain: practically all main line running was under ‘absolute block’ signalling, meaning only one train was allowed in a section, but where a mass of freight trains on goods lines operated it could be under ‘permissive block’ operation.

This would be indicated as the engine passed a signalbox where it operated, and the train brought practically to a standstill, the signalman then waved a green flag, indicating a train was in front of you and to proceed with caution.

At the approach to exceptionally busy marshalling yards, such as those at New England, you could often be behind not just one other freight train but very often four or five. This was equally so from the London direction at Crescent Bridge signalbox where, on several occasions, Hornsey crews having waited for up to two hours, would throw the fire out, make the engine safe and go home on the first available train. You didn’t mess about with Hornsey crews!

Fortunately, at New England shed there was always a considerable number of spare crews available throughout the 24-hour day especially for this purpose.

However, before a running shed foreman sent out a crew to relieve you, his first consideration was to calculate how many hours overtime you had already worked, bearing in mind the fact that you required at least 12 hours’ rest to be available for your rostered 2.30am shift duty the next day.

If not it would mean the list clerk (the person responsible for preparing the daily shift roster) being notified to find a replacement crew for that next day’s particular working.

At that time, every large motive power department had numerous ‘spare’ crews booking on duty every two hours simply to provide cover for these particular duties, plus sickness, additional workings, holidays etc.

On this day we were fortunate as we must have been relieved, as according to my diary, where I recorded every firing turn I performed during my 10-year footplate career, we both worked this train for the next five days.

Today, however, it is obvious that the numerous railway companies in operation on our railways at present do not obviously carry ‘spare men’, which explains why so many trains are cancelled due to the lack of a crew.

Every seven minutes

After arriving in Westwood sidings, the large number of coal trains would be sorted out for their relative destinations in London, later to be hauled by one of New England’s many Austerity 2-8-0s. At one time it was reported that one of these coal trains would depart every seven minutes, such was the need for coal in the London area.

Although it was only a distance of 75 miles, it is hard to believe that it would take around eight hours for these loose-coupled, unbraked freight trains to reach their final destination at Ferme Park, London. But that’s another story.

This, I agree, seems a most archaic way of operating the bulk of freight trains in those days and must take a great deal of believing, but it is entirely true. However, this was the practice at that time and accepted by all over many, many years, especially as slow freight link crews made a considerable amount of extra overtime pay. How wives and families coped with it is questionable, but they did.

Finally, may I say, although I didn’t realise it at that time, my diary has been a godsend to me to be able to recall those days, which although were extremely arduous at times, brought back some fabulous memories of a job I really cherished and was sad to leave.

But times had changed and as the modern diesels took over it caused a mass of depot closures, together with the inevitable redundancies. So, reluctantly, it was time for me to move on.

Archive enquiries to: Jane Skayman on 01507 529423 – [email protected]

Advert

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.