The National Coal Board railway in the Dulais Valley was unique. Geoff Silcock recounts some of the incidents that punctuated the line’s last few years, including an encounter with a then unknown journalist…

into the 1970s two NCB Austerity 0-6-0STs; Hunslet-built Norma and a Bagnall dubbed locally ‘The Flying Dutchman’ regularly lugged 200-300 tons of empties up and the fulls of anthracite coal, sometimes a lot faster than expected, down the Dulais valley on the Graig Merthyr system based at Pontardulais near Swansea, on the prevailing 2½ miles of 1-in-40 gradients and 45-degree curves.

There was a time when the M4 only stretched its concrete swathe as far as the outskirts of Swansea, and the main road onward to the west was the A48, with the first town of note to the north-west being Pontardulais, with its approach marked by a descent into the town of 1-in-12.

Few of the travellers then would have noticed the battered NCB level crossing gates at the foot of the hill, except when they were opened for rail traffic. Indeed, some still didn’t, which explained why they had become so battered into the 1970s.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

An American on holiday stopped at the gates, saw the Austerities at work, and stayed for three days; a Dutch couple likewise in their caravanette for a week. Their particular stay must have made a lasting impression on the NCB loco crews at the time, as the Bagnall Austerity No 2758 was then duly christened ‘The Flying Dutchman’, with the name painted on both sides of the running plate in their honour.

A left turn after the tubular crossing gates took the casual observer into the tranquil, though sometimes turbulent world of Austerity 0-6-0STs Norma and ‘The Flying Dutchman’ in their daily toil to supplant the forces of gravity on the way up, and as explained to me, the same Newton’s law with the steam brake on the corresponding trip down again.

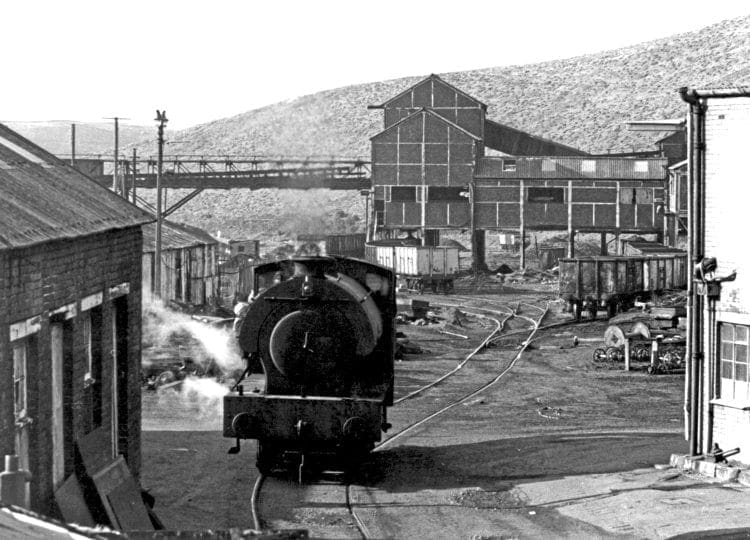

The other Austerity had the less exerting job of shunting wagons into, and out of ‘the dump’. This was a no man’s land where mainly ‘duff’ (coal dust) was blended (mixed) with that from several other locations, and even from as far away as Poland and Australia in those days. After blending, the ‘duff’ was loaded again in the empties for transportation to the nearby Cardigan Bay power station.

Originally a wagonway

The NCB Graig Merthyr system was also the working world of Dai James, Phillip O’Neill, ‘Sparrow’, ‘The Sampler’, Tommy Philpot and Elvet with young ‘Marco Polo’, and a supporting cast of many more, brought together for the operation of the steeply graded 2½-mile line linking the drift mine high in the Dulais Valley with Pontardulais and the outside world.

The Graig Merthyr drift mine was one of the earliest recorded in the Swansea area, and was originally served by a wagonway. It is believed that the original track was strengthened in the early part of the 20th century and the original tunnel at Gopa cutting was blasted out to permit the use of standard gauge steam locomotives and rolling stock up the valley.

From the 1970s until the closure of the line, Austerity 0-6-0STs Hunslet No. 3770 of 1952 and Bagnall No. 2758 held sway, both latterly with the cannibalised parts of two Austerity hulks by the loco shed at Pontardulais.

An on-loan BR 350hp class 08 diesel electric shunter arrived as their replacement once, with the story consequently handed down as a part of the mystique, that the BR instructor who brought it up the valley line wouldn’t bring it back again with a decent load, as he believed that it wouldn’t hold down the tonnage on the 45-degree Gopa curve down the 1-in-40 incline in inclement weather, whereas the Austerities were regularly bringing down 300 tons, and sometimes more throughout the seasons.

That fact that some trips came down the valley faster than others couldn’t be denied, and in the mid-1970s there was the spring day that Norma ran away en route with the regular 12 loaded 16-tonners.

With Calvin the shunter and Dai James still on board, the short bursts on the steam brake had little effect on the situation, and the regular pointsman, Tommy Philpot, further down in his hut at Gopa, then had the unenviable decision to make, in that in pulling the catch point he would send both the loco and train to certain destruction.

In the event he compromised. He let Norma and two of the 16-tonners over, then threw the catch point full over, and ran for it! After the couplings broke under the strain of the remaining wagons, those at the back stayed upright, while the front ones ground into a remarkably neat heap.

Amidst shrill whistling Norma and the remaining wagons managed to negotiate the 45-degree curve and the falling 1-in-40 gradient to the A48 crossing gates, which had been opened just in time ahead

of them…

Still out of control, Norma screamed through, with both 16-tonners bouncing along behind, until they both deserted the Austerity on the first set of points, one demolishing a small hut on the right, while the other badly scored the weighbridge building itself to the left of it.

Happily, being a Friday and close to lunchtime, there were not that many of the regular staff there to witness the occurrence, as most had left early for the weekend.

The outside world would never know, even to this day, whether the regular amount of wagon brakes were not pinned down due to an oversight on the shunter’s part, or whether the screens had overloaded the mineral wagons, which, in turn, had become saturated with water content while awaiting transit from the colliery, though maybe it was something of both. There was one thing for sure though, and that was that no one was saying…

Cold in winter

As an interesting example of early conservation, the local hewn coal from the pile-up at Gopa disappeared to the locals in the first week, in what was termed a whisky galore operation on a grand scale, plus the wheel bearings also found another home.

And when the official scrapmen came to clear the hulks of the wagons, they found that the remains of the mineral wagons had become temporary accommodation for the local feral sheep that scavenged the valley searching for sustenance from visitors.

The Dulais valley could be cold in winter, and we were glad of the warmth from the stove in Tommy Philpot’s hut more than once. It was situated at what had been the previous Gopa Halt for the miners’ trains with wooden benches fitted in boxvans that operated into the 1960s.

It was between trains one day when I asked Tommy the time, and without recourse to his antique fob-watch that he treasured, he pointed out a lone heron, skimming the stream that tumbled along the Dulais valley, and also beside the line for much of its length.

Tommy replied that it would be about a quarter past 10, and recounted that there used to be a pair of the fine creatures until someone had shot one of them. He added that it was such a waste, and that the remaining one would return about 10 minutes later.

It did, but it did not venture near us, though Tommy enthused that it would hover there when he was alone, and through time and patience he had come to befriend it by leaving sardines from his sandwich tin lunchbox for its delectation.

With Dai and Phillip in charge, Norma rattled past with a train of freshly-cut anthracite for the outside world, and the next arrival down the track from the colliery proved to be Tommy’s favourite squirrel, which stopped for some titbits, and then scampered back on the other rail from whence it came.

Whenever I saw that particular squirrel, it came down on one rail and returned on the other, so are all squirrels in South Wales still right-hand drive? But I digress, for at its zenith the Graig Merthyr system had so many people rich in character and understanding.

At the locomotive shed at Pontardulais, the day would start at 5am, when both Austerities were lit up, and by the time the usual pairings of Dai and Phillip, and Calvin, John plus Gereth came on duty at 7am, the water would be bubbling through the thin layer of liquid rust in the gauge glasses.

After oiling up, both locomotives would venture out into a generally soggy dawn. The coal for the engines was specially brought in by 16-ton wagons from other pits in the locality, as the local anthracite was especially volatile and burnt through the firebars, with discarded examples strewn around in disarray as evidence.

We did wonder why this should be, and the answer was simple – the footplate staff were leaving the ‘good stuff’ in small heaps by the side of the line for their ‘regulars’, with payday usually on Friday. The shortfall was then made up with the local anthracite, hence the collection of distorted firebars…

It was told, but never proved, that after one dispute about an unpaid amount for this extra ‘service’, on one of the next downward passes of the stone property involved, a sizeable chunk of anthracite was heaved out of the cab of an Austerity at speed, and as a rolling stone, it succeeded in partially demolishing the aforesaid person’s back wall, though (in jest we thought at the time) it was said that they were really aiming for the outside privy, as the incumbent could well have been inside it at the time of the incident…

Yet, on the surface, the Graig Merthyr system was run with a great degree of efficiency, since the head of the PW department had been made up to be the line manager.

On one occasion, he invited one of our trio, Bob Noble (Noggin), to visit his bungalow while we were at the railway, and Noggin came away convinced that it was by far the best in the district, though in the main it had been paid for by the extra lucrative activities allegedly in operation on the line.

The situation wasn’t unique to South Wales coalfields however, as in 1979, on a visit to the remaining NCB steam locations in Scotland, we were offered by its crew the Barclay builders plates that were still on the working ‘puggy’ that we had come to see, and that we were riding in at the time.

The TPO (Travelling pinta operation)

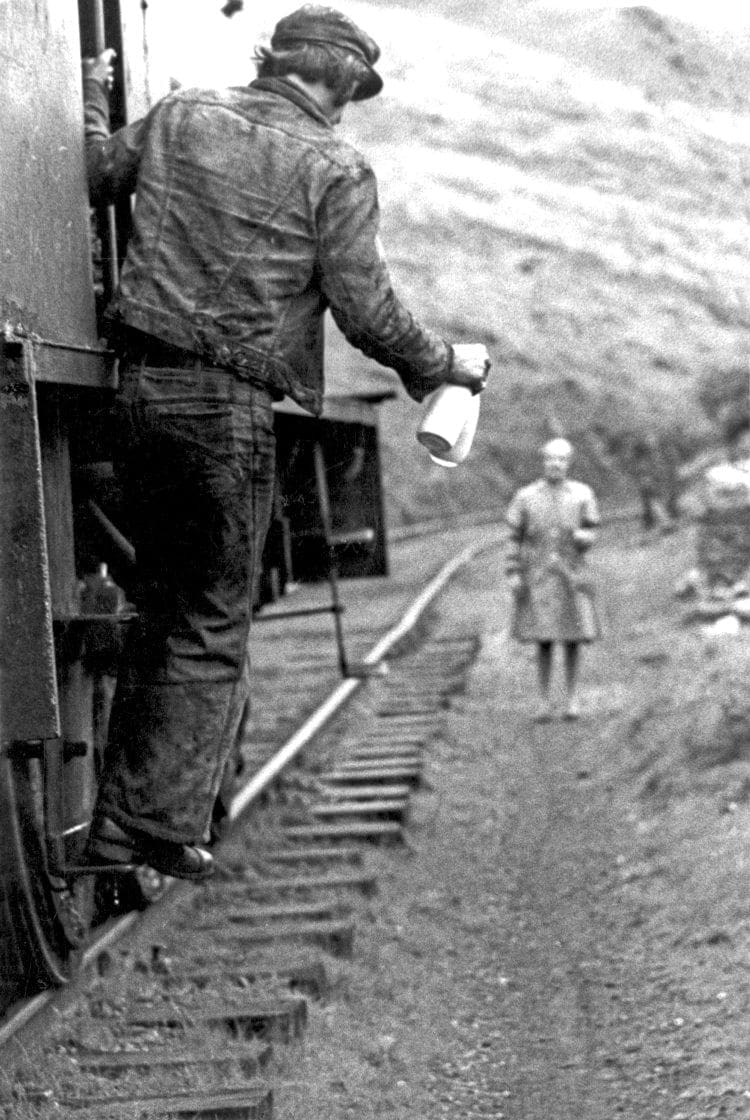

Acts of kindness abounded, though normally away from direct NCB authority, but perhaps the regular ‘milk run’ to Annie Davies was unique.

It had evolved that normally on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, Annie’s two silvertops were delivered to Gopa Halt to Tommy on the milk float that clattered up the rising lane from the main A48, and from there they were scooped up without stopping by the crew of the second train of the day, and set down to Annie a mile or so further up by her cottage in the wilds of the Dulais valley.

I felt at the time that this ‘TPO’ operation was something that just had to be captured for posterity so, armed with my newly-acquired Canon AT1 with autowind, and after removing the largest stones, lumps of coal of course, and some encroaching vegetation from the line’s footpath alongside widow Annie’s stone-built house, some trial jogs were made, until I could keep up with the train labouring uphill beside me, while not looking at my feet, and plus staying focused at what was happening ahead of me as I trotted alongside the line…

So on the next of our visits, the regular crew of Norma, Dai James and Phillip O’Neill, were asked earlier on in the day to pass Annie’s cottage “a bit slower” (these became infamous last words) on that day’s milk run. Annie was now waiting patiently for her pintas to appear as normal, so after Norma hove into view, with Phillip already leaning off the footplate, after letting the loco and then letting 1-2-3 mineral wagons pass me, I started my jog at the same speed as the train.

That was when the plan began to unravel, for as Dai revealed to me later: “I wanted Phillip to sweat a bit getting back on…” so he opened the regulator again. Phillip’s exaggerated slow-mo pace, as in the film Chariots of Fire, then increased with the train’s motion, and of course, mine also.

Phillip then thrust the pintas at Annie and, unburdened, he was long-gone in the pursuit of Norma. The impact of the silvertops at speed spun Annie round, and she fell into my path, with my fast jog coming to a sudden halt, and we fell in a heap, though somehow between us we kept both the pintas and the camera intact.

Ahead of us, Phillip, as he swung aboard the fast disappearing Austerity, let out one of the loudest expletives to Dai, though it was followed immediately by raucous laughter from them both that seemed to crackle around the valley into the distance, and it seemed the same from my companions Big Al and Noggin, who had observed the proceedings from nearby.

Poor Annie was overcome by it all, and although she didn’t share our mirth, after she had been dusted down, she still happily dispensed lemonade made with the local spring water whenever we called in future visits to see her, though perhaps understandably, tea was off the menu…

Bruised and bloodied after getting the auto-wind sequence, I was determined to maybe have the last word on the day, though without offending our regular hosts, so I left a note on the bothy table for Dai and Phillip that simply said: “Same time next week then…” signed by The Boys from East London, though we found out on our next visit that Annie had made alternative arrangements for her deliveries of milk after that.

The seam of anthracite coal at Graig Merthyr was becoming harder to follow, and production was winding down, until only one of its Austerities was required each weekday. Those men who had gradually become our acquaintances over the years were transferred away, until only a handful remained.

Austerities Norma and No. 2758 soldiered on, until in April 1978 the official notification came through that the Graig Merthyr drift mine, along with its connecting railway, would close on that June 23.

Native rhododendrons

Previously, we had spent mostly every second or third Friday at the line and then in early May our trio spent three days in the area. Unusually, for the first two there was hardly a cloud in the sky, and it became uncanny walking up the Dulais valley at 7am in shirtsleeves in the still of the early morning. The prickly gorse had been in flower a few weeks previously, and now it was the turn of the native rhododendrons to burst into bloom.

The acres of ferns that turned to a rusty hue in the autumn were now a mushy green again, and Annie’s 47 scraggy semi-feral sheep seemed to be everywhere observing our movements. Rabbits that seemed to have no fear gambolled and leapt out at us, as we trod the main pedestrian highway up that part of the Dulais valley alongside the well-worn spiked track, with it seemed the only intrusion was from the spindly tall pylons that threaded the striding hills together at a distance.

Austerity Norma’s progress to the Graig Merthyr Colliery in those two days seemed one of pure energy, and it seemed that the Dulais valley sides flung back each exhaust beat louder than ever before in our presence.

The final word on the Graig Merthyr Austerities at the perceived closure would go to Dai James, now the regular driver of Norma, who was accompanied on the last revenue-earning trip ‘up the mountain’ on June 23 by a prim young lady journalist from a syndicated paper, whose name at the time I understood to be Anne Robinson.

This then extremely personable young reporter had been coaxed by one of the ‘Boys from East London’ (who really should have known better) to stand in the Austerity’s half-empty bunker for its last official trip back down the Dulais valley, in what would soon became torrential rain, so she could “visually grasp the effect of the final run back at first hand…”

Dai did admit later that maybe someone might have been banging on one of the cab windows to be let down after the drizzle had started, but there was so much else going on, and besides that, the Austerity was already in motion.

It was on Norma’s arrival at the engine shed a short time later, complete with Welsh and English flags and wreath up front, that the ensemble (including this now rather strange looking person remonstrating in the bunker) was greeted by an assembled group of locals, NCB officials, other local press and, of course, our own motley trio from East London.

After the junior hack’s impromptu voyage back to the valley floor, Titanic-like at the helm of Norma, her lank hair and make-up were now grotesquely dishevelled and, it was recalled later, not unlike Alice Cooper’s stage make-up on a bad night. Her business jacket and multi-laddered nylons were caked in the ever-present clammy now fluid coal dust, and I recall that she was still clutching what remained of her mid-heeled shoes, along with her sodden notebook.

She looked visibly shaken, (some said even whimpering) from her first and last Austerity white knuckle ride down to the valley floor, and it was by way of consolation, after she had been released from her isolation, that Dai James sidled up, and softly spoke these now oft-quoted words of wisdom in his soft Welsh burr voice: “We did have a diesel here once, but it just wasn’t the same…”

After the much-orchestrated closure procedure, the ‘dump’ and exchange yard were kept open until just into 1980, with Dai in sole charge of Norma or No. 2758, but these occasions got fewer and fewer.

On our last visit in January 1980, it seemed like old times again. Norma was in fine fettle, it was a crisp bright day, and we ran over what was left of the system.

There was even a cheeky sprint onto the BR metals in order to pick up some newly-arrived wagons to go to ‘the dump’ for blending, before the big brother class 37 diesel could intervene otherwise.

Last day’s wreath

Both the working Austerity 0-6-0STs from their time on the Graig Merthyr line made it into preservation, and Dai James saw to it that the blackened remains of the last day’s wreath were still in position when Norma was taken away to its new home at Oswestry in 1980.

I understand the former boiler of Bagnall No. 2758 is also still in Wales nowadays, fitted to the Austerity Welsh Guardsman on the nearby Gwili Railway from Carmarthen in West Wales.

When en route to the Gwili, 30-plus years on from the endeavours of the ‘Boys from East London’ a return visit revealed a ranch-type bungalow occupying the space where the engine shed at Pontardulais once stood, with much of the former trackbed beyond towards the M4 now a red brick housing estate.

Further up the now mainly-deserted Dulais valley, Annie Davies, her 47 sheep and two sheepdogs were long gone memories, with her former stone cottage deserted from the 1990s when she passed away, so I was told.

…And that wide crumbling path next to it; well once upon a time there once ran a railway line like no other…

Out of the buildings of the day I’ve stepped

To hermits’ huts, and talked to ancient men.

Out of the noise into the quiet I ran…

Out of the Pit – Dylan Thomas

Read more News and Features in Issue 234 of HR – on sale now!

Archive enquiries to: Jane Skayman on 01507 529423 – [email protected]