By Ian Crowder

THERE were jokes a-plenty about the weather as some 500 people gathered at the Gloucestershire Warwickshire Railway’s Toddington station to witness what many thought that they might never see.

The joke is that on its first steaming last August, and subsequently, it always seemed to rain but no-one could complain about what was a glorious day in every sense.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

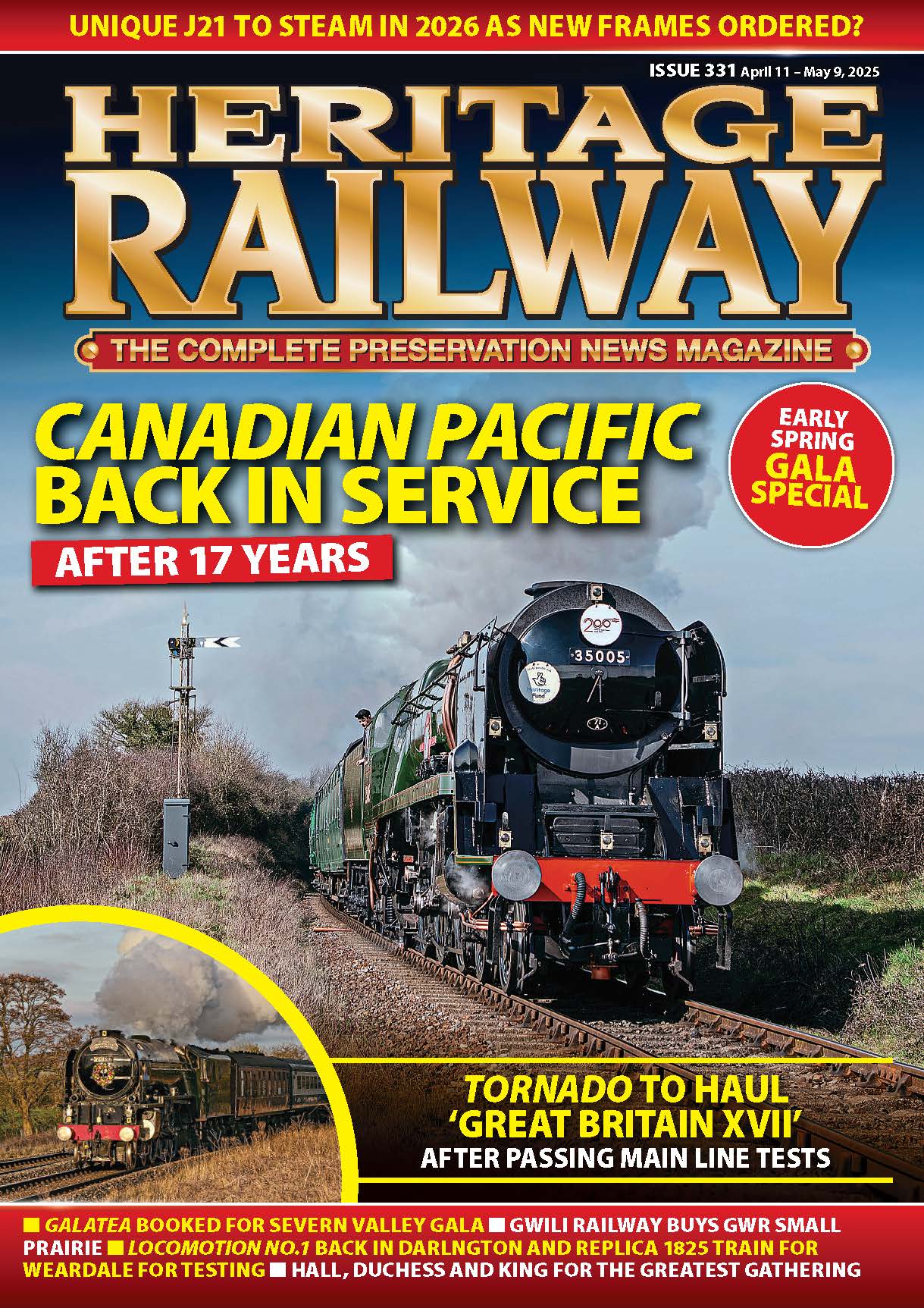

For Monday, May 16, was the day that more than three decades since a stripped, forlorn and rusty Bulleid Merchant Navy Pacific No. 35006 Peninsular & Oriental SN Co. arrived at Toddington for restoration, it hauled its first passenger trains.

Bringing the engine back to life has been a huge technical challenge that meant an early restoration estimate of ‘seven to 10 years’ was wildly optimistic!

No. 35006 was little more than a boiler on wheels – most useful components had been removed for other locomotive restoration projects – even the tender was missing from an engine that had stood for 18 years in the seaside scrapyard of Woodham Bros at Barry.

The vision to liberate

Society chairman John McMillan movingly opened the day’s proceedings by reminding the audience of those no longer with us, who had the vision to liberate the locomotive from its potential fate at the scrapman’s cutting torch and bring it to the embryonic heritage line at Toddington in 1983.

Bill Trite, one of a small number of people who were seeking to rescue a locomotive from the yard, recalled the challenge of raising enough money – £7245 including VAT – to buy what was left of the engine from Dai Woodham, who was threatening to cut up the remaining locomotives resting (or rusting) in his yard.

Now the owners of this once-proud SR express locomotive had to raise another £1300 to take it away and start the long and costly process of bringing the engine to life.

An early pioneer of the project was the late Keith Marshall who, Bill Trite recalled, brought his 15-year-old son Andrew to one of the first meetings of the society.

Since then and for much of the restoration, Andrew has been the engineer steering the project to its fruition. Movingly, and with his voice breaking, Bill recalled Keith and others who had the faith to put their money and effort into seeing that this day would eventually come.

Bill then handed over to 70-year-old David Brown, a fireman based at Yeovil who worked P&O’s final journey. He recalled that he had worked a Yeovil to Eastleigh mail train with the engine, then returned it to its home depot at Salisbury.

“He said: We took it on shed and started to dispose of the engine and the foreman came out – ‘Don’t bother too much lads, it’s being withdrawn’.

“We couldn’t believe it. It was a fine engine, nothing wrong with it and only 23 years old, but its place was being taken by Warship diesels on the West of England expresses.”

David was 18 at the time but seeing the engine in steam again brought the memories flooding back. He later got to fire ‘P&O’ again and pronounced that it was ‘like new’ – which, of course, it is.

Finally, G/WR president Pete Waterman, who himself started his working life as a fireman based at Oxley, pronounced that while he was a Great Western or North Western man at heart, he had huge admiration for the work of designer Oliver Bulleid, especially the design of the boiler.

He reminded guests: “If you believe in something strongly enough, it will happen!” With that, he said, “I name this engine P&O, sweeping back the curtains to reveal the gleaming nameplate that spells the affectionate name P&O out in full: the elaborate nameplate displaying perhaps the longest name carried by a steam locomotive.

Close connection

P&O is one of 30 members of its class, all named after shipping lines that served Southampton Docks – a clever piece of PR by the Southern Railway’s publicity gurus, as it underlined the close connection between the railway and merchant shipping. The name P&O survives to this day, unlike the names applied to most of the rest of the class.

After the ceremonial drawing of the curtains, P&O then gave a performance worthy of a standing ovation. Taking a 12 coach train to Cheltenham and back twice, seemingly with no effort at all, the engine entered traffic for what hopefully will be a long and profitable career on the line. It is the only Merchant Navy that is currently steamable – the other three restored examples are currently out of traffic and the rest of the 11 survivors have yet to be steamed.

Flying Scotsman may have stolen the national headlines over recent months, not least its cost to the nation of more than £4.2 million, but surely this is a locomotive restoration that has taken more effort, more expertise, imagination, ingenuity, sheer goodwill and, above all of these, passion.

And using largely volunteer labour the cost of restoring P&O – including new tender and manufacturing hundreds of new components? Less than £500,000.

In February, the Heritage Railway Association’s John Coiley Award for Locomotives 2015 was won by the

G/WR and the 35006 Locomotive Company Ltd for its restoration “to an exceptionally high standard for future use on the railway”. The locomotive was rostered for its public debut at the May 28-30 Cotswold Festival of Steam.

Read more News and Features in Issue 234 of HR – on sale now!

Archive enquiries to: Jane Skayman on 01507 529423 – [email protected]

Advert

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.