To the untrained eye, Brighton’s Volk’s Electric Railway may appear to be just another seaside tramway, a relic from the resort’s Victorian heyday. However, it is no less than Britain’s first electric railway, and the oldest in the world to be still running, and therefore of paramount international importance.

Magnus Volk did not invent the electric railway. However, he brought the concept to Britain, and switched the country on.

The son of a German clockmaker, Magnus Volk was born at 35 (now 40) Western Road, Brighton, on 19 October 18 51. Locally educated, he became apprenticed to a scientific instrument maker but on the death of his father in 1869 returned home to assist his mother run the family business. His real interest, however, lay in the worlds of science and engineering, in particular anything that worked on electricity.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

In 1879, he successfully demonstrated the first telephone link in Brighton. The next year, he connected the first residential fire alarm to the fire station.

In 1880, he became the first resident of Brighton to fit electric lights to his house at 38 Dyke Road, and over the next four years went on to fit electric incandescent lighting to the Royal Pavilion and its grounds, the Dome, the town museum, art gallery and library. Contacts made during this work proved instrumental in his most famous project of all.

On 4 August 1883, Volk unveiled a quarter-mile long 2ft gauge electric railway running from a site on the seashore opposite the town’s aquarium to the Chain Pier. Power was provided by a 2hp Otto gas engine driving a Siemens D5 50-volt DC generator. A small electric car was fitted with a 1 ½hp motor giving a top speed of about 6mph.

Electric traction was by no means new. The first known electric locomotive was built by Scotsman, Robert Davidson of Aberdeen, in 1837 and was powered by galvanic cells. Davidson followed it up with a bigger locomotive named Galvani, which was exhibited at the Royal Scottish Society of Arts Exhibition in 1841.

This second locomotive was tested on the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway in September 1842, but the limited electric power available from batteries prevented its general use.

The world’s first electric passenger train was demonstrated by Werner von Siemens in Berlin in 1879. It locomotive was driven by a 2.2 kW motor and the train which consisted of the locomotive and three cars reached a maximum speed of 13km/h, and over four months the train carried 90,000 passengers on a 320-yard circular track.

The electricity, provided by a nearby stationary dynamo, was supplied to the train through a third isolated rail situated between the tracks.

In 1881, the world’s first electric tram line, also built by Siemens, opened in Lichterfelde, near Berlin, Germany. The idea of an electric as opposed to steam locomotive may have originated in Scotland, but Volk brought it back to Britain in the form of a workable concept.

He soon sought powers to extend his westwards along the beach to the town boundary, but the council refused. Instead, he obtained permission to extend eastwards from the Aquarium to the Banjo Groyne and the Arch at Paston Place to provide workshop and power facilities. He also decided to widen the track to 2ft 8½in gauge, and he designed two more powerful and larger passenger cars.

The route followed the seashore, and needed timber trestles to bridge gaps in the shingle, and severe gradients down and up to allow the cars to pass under the town’s Chain Pier.

The new line opened on 4 April 1884, at first using one car. The upgraded power plant in the Arch gave an output of 160 volts at 40 amps, more than enough to propel the two new cars along the 1400 yard-long railway. A loop complete with halt was provided halfway along the route for the cars to pass.

With the arrival of the second car, a five or six-minute service was provided daily, summer and winter, excepting Sundays, until 1903. The service operated until 1940 when the threat of invasion dosed the railway during World War Two.

While local cab drivers and fishermen working from the beach were not impressed with the competition from the railway, it was a huge hit with the public. Two new cars, Nos 3 and 4, entered service in 1892, and a fifth car followed in 1897. In 1890, frustrated at his inability to extend beyond the Banjo Groyne to Rottingdean, it being blocked, Yolks produced a scheme for a new kind of railway which ran through the sea itself.

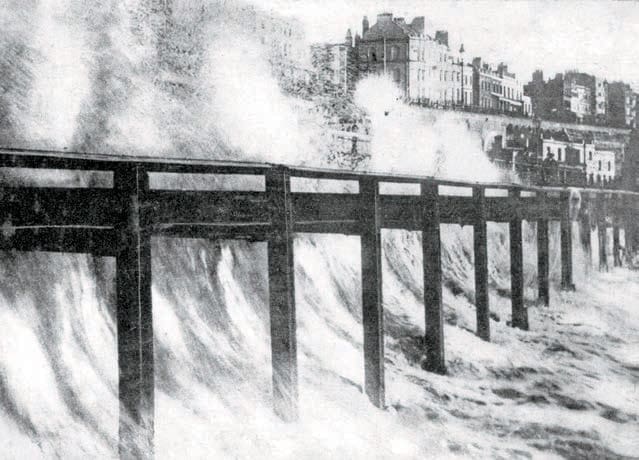

The Brighton and Rottingdean Seashore Electric Railway consisted of two parallel 2ft 8½in gauge tracks, billed as 18ft gauge, the measurement between the outermost rails. The tracks were laid on concrete sleepers mortised into the bedrock.

The single car used on the railway was a 45ft by 22ft pier-like building which stood on four 23ft-long legs and weighed 45 tons. It was powered by electric motor.

It was officially named Pioneer, but many called it Daddy Long-Legs and the nickname stuck. Not only did it need a driver, but a qualified sea captain was on board at all times.

Uniquely in British railways again, the car was provided with lifeboats and other safety measures. Building of the second line began in 1894 and it officially opened on 28 November 1896, only to be severely damaged by a storm a week later.

Volk rebuilt the railway, including Pioneer, which had been turned onto its side, and it reopened in July 1897. The railway, arguably the most eccentric in Britain, also proved popular, but faced difficulties. High tide slowed the cat down, and Volk did not have the finance to install more powerful motors.

In 1900, groynes built near the railway to prevent beach erosion were found to have led to underwater scouring under the sleepers and the line was closed for two months while repairs took place. The council decided to build a beach protection barrier, and told Volk to divert his line around it. He could not afford to do so, and so closed it.

The track, car and other structures were sold for scrap, but some of the concrete sleepers can still be seen at low tide. A modern-day comparision might be made with the unique sea tractor at tidal Burgh Island at Bigbury-on-Sea in south Devon, which takes passengers from the mainland to the island at high tide, on a platform carried on stilts.

After the Brighton & Rottingdean Seashore Electric Railway venture failed, Volk obtained permission to extend his first line beyond the Banjo Groyne to Black Rock and opened the extension in September 1901, bringing the total length of the railway to one-and-a-quarter miles. The longer line needed more cars and three were added, and by 1926, the fleet had been brought up to 10. The last car built specifically for the railway was a winter car, which arrived in 1930.

In 1930, the redevelopment of Madeira Drive saw the railway cut back at the western end to a site opposite the aquarium. It was a setback for the line as the terminus was now no longer next to the pier entrance.

Sadly and short-sightedly, the line was also cut back by several hundred yards at the Black Rock end. The council decided to build a new swimming pool on the land currently occupied by the station and so cut the line even shorter.

The new Black Rock station was opened on 7 May 1937, when Volk, then 85, and the deputy mayor and Magnus Volk took joint control of Car 10 for a journey. It was Yolk’s last public appearance as he died peacefully at home13 days later. He is buried at St Wulfran’s churchyard in Ovingdean near Brighton.

Control of the railway passed briefly to his son Herman. However, the 1938 Brighton Corporation (Transport) Act gave the local authority the powers to take over the railway.

At first the line was leased back to Herman, but on 1 April 1940 the corporation took full control, the last train running three months later before closure for the war years.

After hostilities ended, the council did much to upgrade the railway, replacing the rails and life-expired buildings. Services resumed on 15 May 1948, but winter services were suspended in 1954 and have been run only occasionally ever since.

Original cars 1 and 2 were scrapped and replaced by two Southend Pier Railway trailer cars which, converted to motor cars became Nos 8 and 9 in the fleet.

During the late 60s and 70s, Brighton began to be severely hit by competition from cheap Mediterranean package holidays. The Black Rock swimming pool closed in 1978, leading to a further drop in passenger numbers on the railway.

Questions were asked as to whether the expense of keeping the railway open was justified, but in the end it was decided to keep the line open at least until its centenary in 1983. That event was a huge success, with Yolk’s youngest son Conrad driving a special train comprising cars 3 and 4. Afterwards, it was decided to keep the line open.

Patronage is reasonably buoyant today, although there are many who have commented that it would be far greater if the line could in some way be re-extended westwards back to the pier entrance, and eastwards beyond Black Rock to the new Brighton marina.

As it is, first-time visitors who head straight from the main line railway station to the pier would not even guess that Yolks Electric Railway exists. Does it provide public transport, or is it a Victorian anachronism limited to novelty value?

This writer believes that the heritage potential of the railway and surrounding attractions is huge. As stated earlier, Yolks Electric Railway was not the first in the world to run on electricity, but all the earlier ones have long since passed into history. It was also the first in Britain. Therefore it should not be dismissed as a local antique, but a national attraction of immense historical importance.

By bringing it to Britain, Volk sowed seeds which may be deemed to have helped with the creation of the London underground and electrified overground suburban lines, the third-rail electric Southern Railway/Region and ultimately the inter-city trunk routes like the East and West Coast Main lines which form a backbone of the country’s provincial transport system. In so many way it was a true ‘first’, and we should be shouting it from the rooftops. Secondly, the British seaside has seen a resurgence in recent years, with the popularity of holiday homes and then more people deciding not to go abroad because of poor exchange rates. Now is surely the time to capitalise.

The railway’s western terminus, Aquarium station, stands opposite the Sealife Centre. However, this building is far more important than just another aquarium in a national chain. Dating from 1872, it is nothing less than the world’s oldest working aquarium, conceived and designed by Eugenius Birch, the architect responsible for the West Pier, which is awaiting rebuilding after being left to decay and then gutted by fire. The interior of the aquarium has been kitted out to look like something from a Jules Verne submarine theme park, and its ambience dovetails so well with the early electric railway that runs outside. While Brighton is famous for the Royal Pavilion, there are enough classic Victorian and Edwardian ‘seaside’ structures and features that could be enhanced to offer a package by which the town could be sold to visitors from both home and overseas who wish to revel in the finer delights of yesteryear, with the railway at its core.

At the time of writing, there is no immediate threat to close the railway, but it clearly could offer so much more. Since 1995, it has been supported by a growing band of enthusiasts under the banner of the Yolk’s Electric Railway Association, who, on occasions, even take over the running of the trains.

If you fancy doing something a little more elaborate than bucket and spading at Brighton, contact the group via membership secretary Alan James, 13 Rudyard Road, Woodingdean, Brighton BN2 6UB, or on [email protected]

Magnus Volk has also been immortalised in Brighton’s own Walk of Fame, the brainchild of local resident David Courtney, the man who discovered pop star Leo Sayer back in the 70s. Based on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, it is the only one of its kind in Britain. All the 100 names are laid in a liner alongside the resort’s waterfront development, and Volk is up there with the likes of Dame Anna Neagle, Ruyard Kipling and Chris Eubank.

In terms of the impact that electric railways had on British transport, maybe he is the greatest Brightonian of them all.

Advert

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.