While banner-waving protestors who gathered outside stations on the last day of services on their local line may have felt that they were wasting their breath against a Government ‘one size fits all’ policy, that the consultation procedures were purely academic, and that the Labour government which pledged to reverse the cuts re-engaged on that promise after it won two general elections in 1964, several lines were reprieved sooner or later.

On March 3, 1964, nearly a year after the publication of the Beeching report, Marples announced that he had refused consent to closure in two cases – the Central Wales Line between Craven Arms, Pontardulais and Llanelli (now marketed as the Heart of Wales Line), and the Ayr-Kilmarnock line in Scotland. He did, however, agree to the closure of the southernmost branch of the Central Wales Line between Pontardulais and Swansea Victoria, from June that year.

Regarding the Central Wales Line, Marples said he had taken on board the fact that it served several towns and villages in central Wales, some of which had no other public transport and few of which had even a daily bus; it also provided a cross-country link between Swansea, west Wales and the north of England. He did accept that some stations and halts were all but unused and told the British Railways Board that he would be prepared to consider their closure.

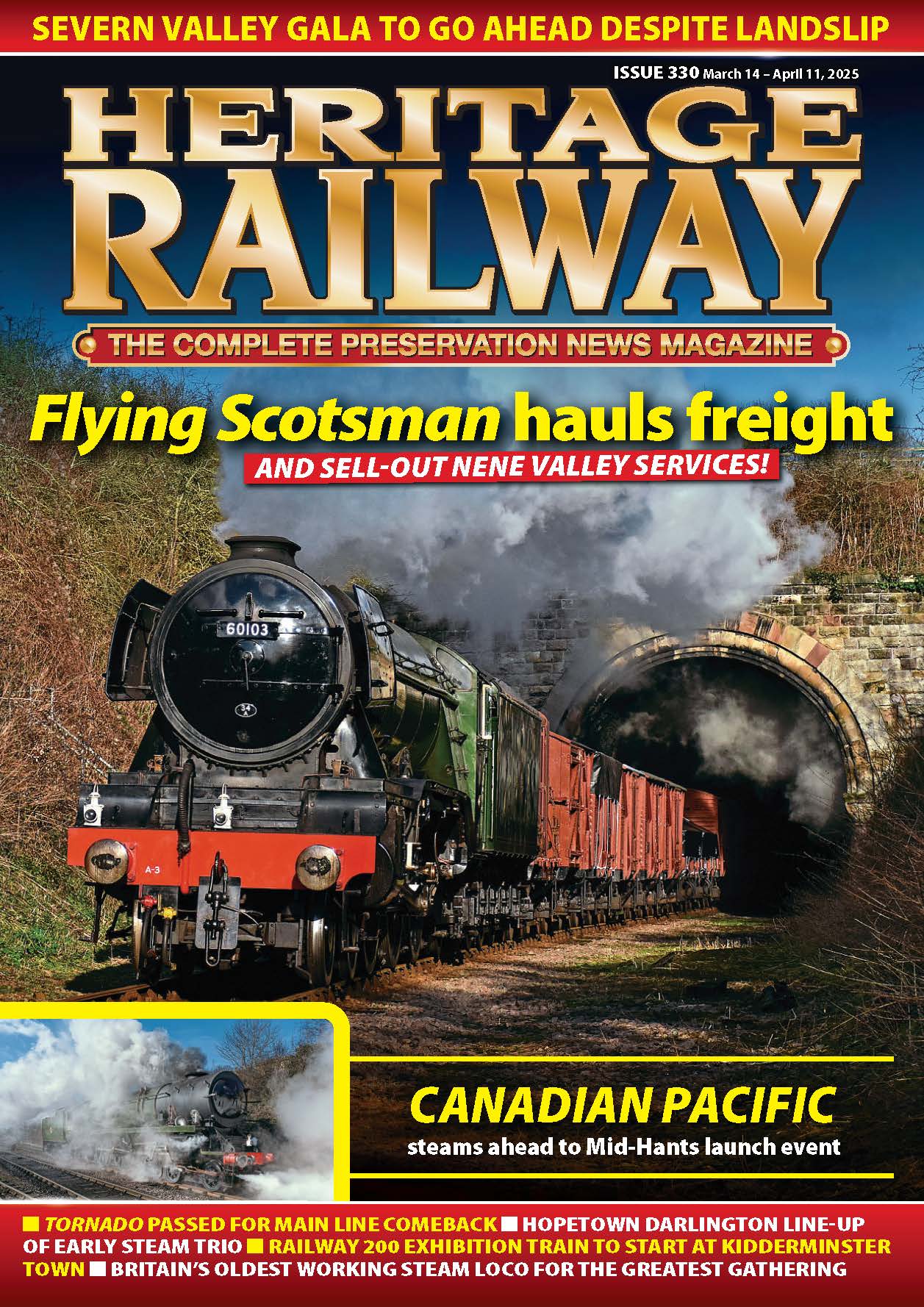

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Regarding Ayr-Kilmarnock, Marples endorsed the finding of the Scottish Transport Users Consultative Committee, but said he might reconsider in another 12 months. Marples said that the railways’ annual operating loss had been reduced by about £17 million in 1963, and that progress was being made, but un-remunerative passenger services listed by Beeching were costing the taxpayer at least £30 million in annual subsidies, a heavy burden which had to be reduced.

Marples said: “That is far from being the case. Most of my consents are not just ‘yes’, they are ‘yes, but…’”. Some of his consents had no conditions except maintenance of existing bus services; others were consents with special requirements for extra bus services; others were consents deferred to give time for road improvements; and yet others were consents with the proviso that warning must be given if British Railways wished to take up the track.

Marples said that he was taking into account all important factors, including social considerations, the pattern of industrial development and possible effects on roads and road traffic. “They also show that in every case, I have accepted the Transport Users Consultative Committee’s view on hardship almost entirely,” he said. “This shows how much I rely on them. I have also nearly always accepted their proposals for extra services to relieve hardship, and sometimes I have gone further than they recommended.

“We look at everything that has a bearing on each proposal – buses, roads, traffic, regional development, commuting needs, holiday travel. All the facts are brought to an official working party, on which all Government departments with relevant responsibilities are represented. They report to me, and I consider each case personally.”

Marples decision on the Central Wales Line came despite observations made by the Transport Users Consultative Committee that between Llandovery and Craven Arms, only the stations at Knighton and Llandrindod Wells were taking more than £5 a day in receipts. Yet the TUCC also said that the withdrawal of services would cause considerable hardship.

Nevertheless, the line was reduced to single track during 1964/5 as an economy measure. A second closure threat appeared in 1967, but the line again reprieved, on social grounds.

Sceptics said that Harold Wilson saved it from closure because it passed through six marginal constituencies. British Rail continued to seek economies despite receiving a subsidy to operate the line, and in 1972, produced a stroke of inspiration, one which might have saved many other lines in the Beeching report. It successfully applied for a Light Railway Order under the 1896 Act for the section of the 78¾ mile section of the line between Craven Arms and Pantyffynnon, even though the line speed is 60mph and not the required 25mph. However, the order still allowed many operational procedures to be simplified and so produced economies.

The future of the line was again thrown into question in 1987 when the Glanrhyd bridge near Llandeilo collapsed after heavy flooding, and an early morning northbound diesel multiple unit plunged into the swollen River Towy, killing four people. The Carmarthen-Aberystwyth line had been closed in 1965 following serious flood damage because the cost of repairs was deemed uneconomic, but in the case of the Central Wales Line, by then there was unanimous support for the line to be saved.

Marples again saved the day

In spring 1964, Ernest Marples announced a reprieve for the heavily lossmaking routes tot he north and West of Inverness, the Far North Line to Wick and Thurso and the Kyle of Lochalsh branch.

If Beeching’s recommendations had been adopted, there would have been no trains north of Stirling.

However, after listening to the powerful Highland lobby, the transport minister agreed that that transport in the region was a special case. At the time there was no realistic prospect of alternative road transport to replace it, and the line closures could cause extreme and widespread hardship for the sake of saving £360,000 a year.

Conversely, British Railways then promised to make the services more attractive to promote greater use by both passengers and freight.

The Kyle line appeared at risk again in the Seventies when the Stornaway ferry was switched to Ullapool, but tourism and again social considerations saved the day. In September 1964, Ernest Marples sanctioned the closure of 38 passenger routes, as recommended by Beeching, but reprieved three others. These were Newcastle-Riverside-Tynemouth, the previous mentioned Middlesbrough-Whitby, and Llandudno Junction-Blaenau Ffestiniog.

He also redeemed two others, the Darlington-Bishop Auckland section of the Darlington-Crook line, along with the Bangor-Caernarfon section of the Bangor-Afon Wen route. He stopped the closure of Newcastle-Tynemouth because it carried large numbers of workers to and from the Tyne shipyards in a badly-congested area. The Tyne & Wear Metro light rail system now links the two.

In the case of the 28 mile wonderfully-scenic Blaenau Ffestiniog line, he was swayed by both by the hardship which closure would cause to local residents, particularly in winter when the road to Blaenau over the Crimea Pass is affected by snow and ice, and also by tourism.

Nonetheless, he agreed to the closure of the stations at Glan Conwy and Dolgarrog.

From 1964, the line was used for nuclear flask traffic to Trawsfynydd power station. The GWR route from Blaenau to Bala which closed in 1961 after being flooded by Llyn Celyn reservoir was partially reopened in 1964 from Blaenau to Trawsfynydd, with a new rail connection built to link it at Blaenau to the line to Llandudno Junction.

Power station traffic ceased in 1998 and that part of the line is now mothballed.

The Blaenau branch is now marketed as the Conwy Valley Line, and in 1982, opened a new interchange station with the Ffestiniog Railway in the town. Glan Conwy and Dolgarrog have since been reopened.

Sadly, while the magnificent Conwy Valley line was reprieved, around the same time another spectacular route, the 53 mile GWR line between Ruabon and Morfa Mawddach via Bala was closed. Two sections have been reopened as heritage lines; Llangollen-Carrog (Corwen scheduled for 2012) as the standard gauge Llangollen Railway, and the length along the shores of Llyn Tegid (Lake Bala) as the 1ft 111⁄2in gauge Bala Lake Railway.

The service between Bishop Auckland and Darlington was retained for use by large numbers of workers from Bishop Auckland travelling to work in the Darlington- Aycliffe ‘Growth Area’. Bishop Auckland was seen as a railhead for the Crook-Tow Law region.

It not only survives today, but links to the Weardale Railway, a largely pre-Beeching passenger closure which has been revived for passenger and freight services by US operator British American Rail Services.

The Bangor-Caernarfon line was spared because Marples accepted that it provided a much better railhead than Bangor for travellers via the North Wales Coast Line to and from places farther south, including Pwllheli and the Butlin’s holiday camp at Penychain. However, his successors did not share the same view.

It was closed to passenger traffic on January 5, 1970. Following the fire that severely damaged the railway bridge over the Menai Strait, the branch and Caernarfon goods yard were temporarily reopened for goods traffic from May 23, 1970 to January 30 1972. Following closure all the track was removed and the station was demolished. Caernarfon had a new station opened on 11 October 1997, but with a line running south along the trackbed of the Afon Wen route for which Marples had sanctioned closure when reprieving Bangor-Caernarfon.

It was the first part of a new Welsh Highland Railway which was being developed by the Ffestiniog Railway and which included the route of its predecessor that had closed on September 5, 1936. The completed and extended new Welsh Highland saw its first public services through to Porthmadog on February 19, 2011, and as that town has a main line station, Caernarfon can now be said to have been reconnected by rail to the national network. The stations at Delphinine and Carr Bridge on the Perth-Inverness line were saved because they serve isolated communities largely dependent on the tourist trade, and are still open today.

Marples took the view that it would be extremely expensive to provide adequate alternative services. However, it still remains the fact that under both him and his Labour successors, far many more lines and stations to which closure objections had been raised were axed.

Settle and Carlisle

Following the closure of smaller intermediate stations in the 1960s, the Beeching report recommended the withdrawal of all passenger services from one of Britain’s most scenic and best-loved routes, the Settle to Carlisle line.

The Beeching recommendations were shelved, but in May 1970 all stations apart from Settle and Appleby West were closed, and local passenger services cut to two trains a day in each direction, leaving mostly freight.

The ‘Thames-Clyde Express’ from London to Glasgow Central via Leicester was withdrawn in 1975, and night sleepers from London to Glasgow using the route followed the year afterwards. A residual service from Glasgow to Nottingham survived until May 1982.

It was clear that the line and its viaducts and tunnels were suffering from lack of investment, and deterioration might yet do the job of the Beeching Axe. During the 1970s, most freight traffic was diverted onto the electrified West Coast Main Line. As a counter measure, Dalesrail began operating services to closed stations on summer weekends in 1974, promoted by the Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority to encourage ramblers.

Yet by the early 1980s, the route handled only a handful of trains per day, and there were those who head the cogwheels turning in British Rail’s mind from afar. In 1981 a protest group, the Friends of the Settle-Carlisle Line was set up to campaign against the line’s closure even before it was officially announced.

Between 1983 and 1984 three closure notices were posted up by British Rail which was determined to shut the route. While the Beeching threat had been staved off, this time BR saw no need for the line which had lost its freight, through passenger services and had a very limited local service. BR also considered Ribblehead Viaduct to be in an unsafe condition, and used it as the key reason for closure, stating that its repair or replacement could cost more than £6 million.

Freight ended in 1983, although more enthusiast steam specials were by then running over it.

As the threat of closure hung over the line, passenger use underwent a resurgence, as packed Class 47-hauled trains carried people wanting to travel the line for one last time. Annual journeys were recorded at 93,000 in 1983 when the campaign against closure began, and had shot up to 450,000 by 1989.

Plans were even drawn up in 1987 to sell the line off to a private bidder. However, 22,000 signed a petition against closure, and eventually, on April 11, 1989, the recently-promoted Conservative Transport Minister Paul Channon announced that the closure notices had been withdrawn. In 1991, work began on repairing Ribblehead viaduct.

The decision was the right one. While it may be easy to justify closing a line because of the current viability, how often are future traffic flows predicted, or how far can they be expected to be foreseen?

Much freight now uses the Settle and Carlisle route due to congestion on the West Coast Main Line, and includes coal from the Hunterston coal terminal in Scotland taken to power stations in Yorkshire, and gypsum from Drax Power Station carried to Kirkby Thore. Significant engineering work was needed to upgrade the line to carry such heavy freight traffic and additional investment made to reduce the length of signal sections.

The line is also used as a diversionary route from the West Coast Main Line during engineering works, while eight of the stations closed in 1970 were reopened. In 2009 a bronze statue of Ruswarp, a collie dog belonging to Graham Nuttall, the first secretary of the Friends of the Settle-Carlisle Line, was unveiled on the platform of the refurbished Garsdale station. It is there to mark the saving of the line by people power, and the fact that Ruswarp is believed to be the only dog to sign a petition against a rail closure originally proposed by Beeching, or any other for that matter.

A fisherman still jolly

In October 1960, Mablethorpe & Sutton Urban District Council voiced concerns when British Railways announced its intention to close the route from Louth to Mablethorpe, the northern part of a loop serving the resort popular with East Midlands and northern families.

As most of the holiday traffic to Mablethorpe and Sutton came over the southern half of the loop via Willoughby, closure of the Louth line was seen as having little impact. There was little opposition to the closure and the last trains ran on December 3, 1960.

Yet while the British Transport Commission said that the remaining services to Mablethorpe from the south would remain, with improved stabling facilities at the resort to facilitate an increased number of excursion trains, councillors remained fearful that within a few years that line would close too.

They were right: British Railways failed to honour pledges to develop holiday traffic to Mablethorpe and Sutton, instead reducing both services and the availability of cheap tickets. For them, it was no surprise that the Beeching report of 1963 proposed the closure of virtually the whole of the East Lincolnshire network.

Lined up for the axe was the original Great Northern railway main line from Grimsby to London via Boston and Peterborough, Lincoln–Firsby via Bardney, Willoughby- Mablethorpe and the Skegness branch.

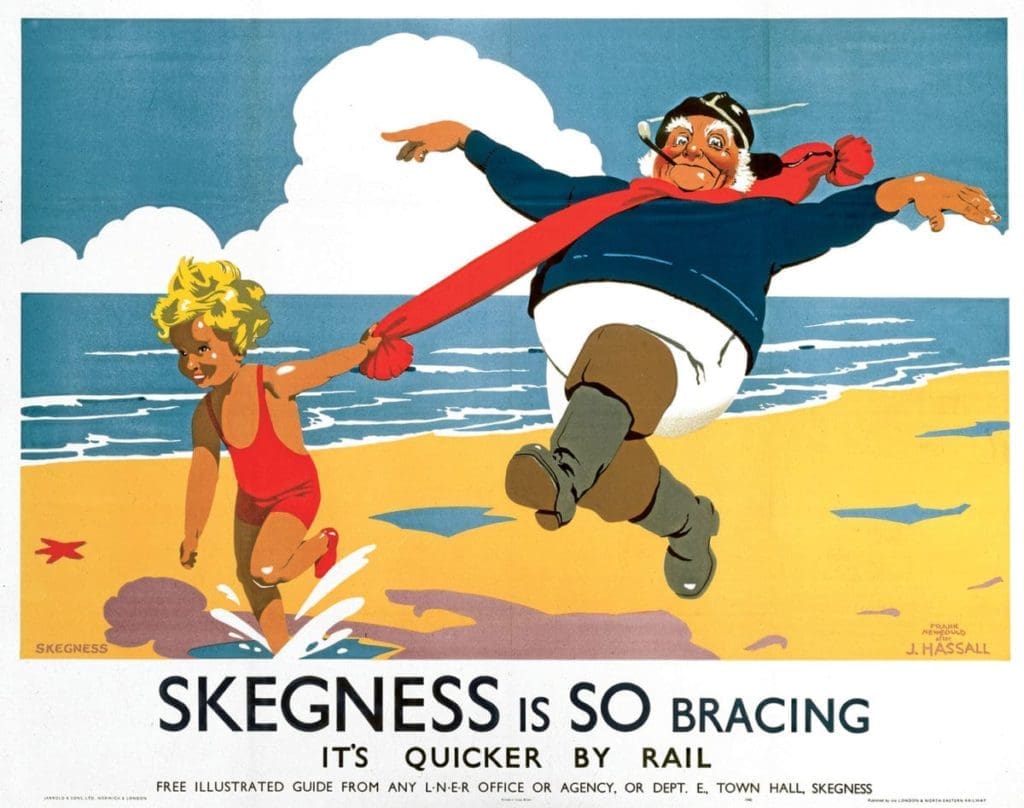

It was the railway that had turned Skegness from a tiny village into a massive resort. The Great Northern Railway’s Jolly Fisherman poster extolling the virtues of the windswept North Sea coastal town because it was so bracing became one of the most famous and successful pieces of railway advertising of all time.

Freight traffic over the Mablethorpe line was withdrawn from March 30, 1964 but opposition to the loss of the passenger services was long and bitter, with a public hearing being held in Skegness on September 15/16, 1964. By the time the hearing took place, in the case of the rundown Mablethorpe branch, British Railways was able to argue that fewer passengers were likely to suffer hardship because by then, local residents had been deterred from using the services by the reductions.

Mablethorpe and Sutton Urban District Council wanted the line to stay because it said that roads from the proposed railhead at Boston were poor or inadequate. The Minister of Transport studied the findings of the inquiry and ordered British Railways to reconsider the closure plans. It did so, and proposed the same closures, but saving the Boston to Skegness line.

A second Transport Users Consultative Committee inquiry was held at Skegness in May 1968 and this time the transport minister backed the requested closures. He said that while closing the Mablethorpe line would affect the summer tourist trade, as at numerous resorts elsewhere in Britain, there were not enough users of the service during the rest of the year to justify keeping the service.

The Mablethorpe line closed from October 5, 1970 and was lifted the following year. Skegness and Boston remain linked to the national network via the route to Sleaford, Grantham and Nottingham, now rebranded and promoted as the Poacher Line. The mass influx of summer seaside specials is now consigned to history, but the Jolly Fisherman remains as the trademark of Skegness.

Advert

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.