This new branch of the North-Eastern Railway, which is now complete, runs across the east coast of Durham from Seaham Harbour to Hart Junction, situated four miles north of Hartlepool. Its course is 20ft, and the distance is half a mile from the cliffs, and from it the sea is visible practically all of the way. First published in April 1903.

The level of the railway is about 60ft to 150ft above the sea. The coastline here is intersected by a number of ravines or ‘denes,’ as they are called in the North, which are very like the ‘coombes’ of Devon and Cornwall, extending from the coast inland and the railway in the course of nine miles crosses no less than nine of these, varying in width from 100ft. As at Hawthorn, to 800ft. at Castle Eden ad Crimdon. Four of these denes necessitated the construction, of large viaducts, while in five other places the line is carried over them by means of embankments overlying culverts varying from three to six feet, in diameter.

The denes are nearly all well wooded, and form a delightful contrast to the surrounding country, which, is swept, by constant gales from the sea, is generally bleak and desolate.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Such is the country traversed by the railway, which considering it is only nine and a quarter miles in length, has been a expensive undertaking, the contract price amount to nearly £250,000.

The idea of making this line originated with certain coal owners, who were desirous of sinking pits in order to win the coal under the sea, as at Seaham an Monkwearmouth, and to bring the coal to the bank and as near to the sea coast as possible, and upon their representations the North-Eastern Railway undertook making the line, an be ready to convey the coal as soon as the mines were developed. Here it may be stated that three pits have already been sunk, but they are meeting with such a volume of water before reaching the coal.

In one case, it has been resolved to freeze around the shaft to an extent that had never been attempted before. This novel experiment upon the part of the man to circumvent one natural force by another is being regarded by the whole of the mining fraternity with the greatest interest, as, if successfully accomplished, it will be one of the greatest triumphs of mining engineering. In the other two mines the water is still being held under control by tremendous pumping.

Another reason for the North-Eastern Railway undertaking the making of this branch is that (as will be seen from the map on this page) it gives an alternative route from Newcastle and Sunderland, to Hartlepool Stockton, and then to Manchester and Liverpool. It has better gradients and curves than their existing route. The worst gradient on the new line (as shown on the gradient profile- page 289) is only one in 100, whilst the sharpest curve has a radius of 33 chains.

As readers of The Railway Magazine are already aware, the existing railway between the towns named is an old coal line, worked originally by stationary engines and ropes, and has almost prohibitive gradients of one in 40 and curves of less than a 20 chain radius.

When the Seaham and Hartlepool Railway bill was put before Parliament, and was proposed to run- by consent, of course-over the private line between Sunderland and Seaham belonging to the Marquis of Londonderry, but the North-Eastern Railway having since bought the Londonderry Railway, the whole route is now therefore the property of the North-Eastern Railway.

As we have already covered, the feature of the new line is the number of viaducts, ad with regard to these; readers will be interested to learn that the Dalton Viaduct has three spans of 50ft, in diameter and two spans of 25ft, and its greatest height from the ground is 60ft.

As the illustration at the bottom of this page shows, it is substantially constructed using brick. The photograph visible on page 287 shows the remarkable viaduct at Hawthorn Dene, about two miles of Seaham. This viaduct consists of one span of 120ft, which is the largest brick arch, with one exception, for railways in England, and five arches of 25ft span and a height of 104ft, from the bottom of the stream which he viaduct crosses.

The middle of the great span alone required 9,000 cubic feet of timber (see illustration on page 288). The viaduct is identical in construction, but it is only 94ft, to the rail. Besides the viaduct, there are twenty small bridges of spans varying from 25ft, to 12ft. Also, there are eighteen culverts. All these bridges except three are arches.

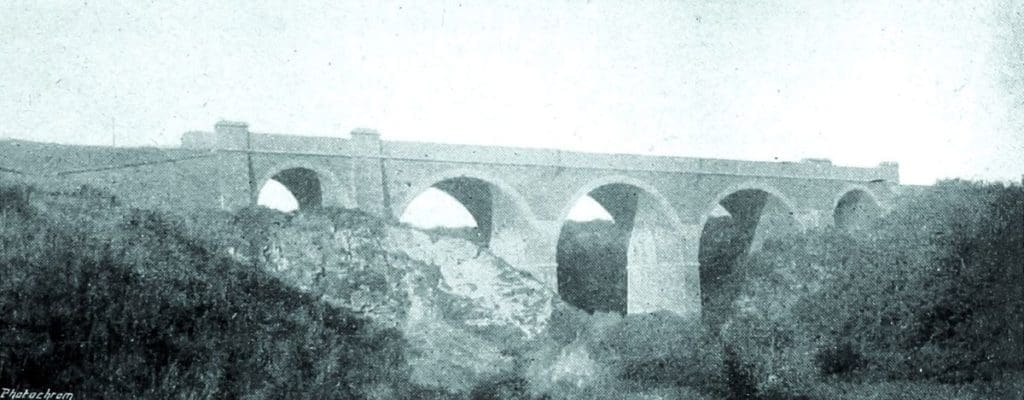

The materials employed in these structures amounted to 50,000 cubic yards of brickwork, 20,000 cubic yards of concrete and 90,000 cubic feet of ashlar, mostly in copings and stringcourses. There were several very heavy cuttings, and the amount of material excavated. The viaduct of Castle Eden has ten arches of 60ft, span and the height is which varied from marl to boulder clay and sand, was 700,000 cubic yards.

The denes at Crimdon and Castle Eden are both wide and deep, with steep sides where the railway crosses them, and a difficulty came as a means of bringing the materials on to the spot for building of the viaducts, but the contractors got past this by using cable ways which spanned the entire width, about 800ft, and by which material was carried to and deposited at whatever pier or arch was under construction. The other seven denes, not being so wide, were crossed by temporary wooden bridges, which used about 106,000 cubic feet of timber.

The scarcity of bricks in the immediate neighbourhood induced the contractors, Messrs. Walter Scott and Middleton, Ltd. Their first Resident Agent was Mr Thomas Thomson, and afterwards Mr Charles Scott, to open out a brickfield close to the site of the railway, and to make their own bricks, but owing to the amount of lime in the clay the first bricks made in the usual way all flew to pieces after the first shower of rain.

To remedy this an expedient was adopted which, through extremely simple, proved eminently satisfactory, and that was to run the bricks in the trucks from the kilns in to a small pond made for the purpose and allow them to remain in the water for about an hour.

A certain amount of effervescence went on during that time, which seemed to have an effect of reducing lime content to putty like substance, and as a result a perfect hard and serviceable brick was made. Eventually, there will be three stations on the new railway, at Blackhall, Hordon and Easington. But, it is not intended to build them until the collieries are ready to draw coal.

Mr Cudworth originally designed the viaducts and Mr Charles Harrison made bridges, but several alternations, especially at Hawthorn viaduct,, the Chief Engineer of the North-Eastern Railway (Northern Division), and the works carried out under the supervision of Mr H Dent, Resident Engineer.

Although, the railway is ready for traffic, the traffic is not yet ready for the railway. A date for opening has not yet been set, but it is expected that when the service of trains are arranged for the coming summer, considerable use will be made of the Seaham and Hartlepool Railway.

Our best thanks are due to Mr C Harrison, the Divisional Chief Engineer of the North-Eastern Railway, for the facts and illustrations which can be found in this article.