Originally published in two parts in The Railway Magazine – August and September 1966

Cannon Street Station, which this month completes one-hundred years of service, is the only station within the City of London which was built by the South Eastern Railway. Both the name of the thoroughfare and the site of the station are of considerable historic interest. Canon (sic) Street appeared in Leake’s map of 1666, but this had been evolved over some 500 years from the early form Candelwykestrete which Stow asserted was derived from “makers of candles”; it certainly had no link with armaments.

The site of Cannon Street Station was occupied for many centuries by the Steelyard of the Hanseatic League. Its ancient trading privileges were withdrawn by Elizabeth I in 1598, but the last connecting link of the site with German merchants was not severed until 1853, and pews in the Church of All Hallows the More were reserved for Hanseats until 1894, when that church was demolished. The word “Steelyard.” also, is derived from sources far removed from the apparent one. Authorities differ as to whether the original word was stillyard (meaning the great beam or weighing arm), or stell (a place of merchandise), but there seems to be no evidence of an association with steel.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Until the 1860s the only railway to penetrate the City of London was the London & Blackwall, which opened its original terminus in July, 1840, at Minories (just within the City boundary), and extended the line to Fenchurch Street in August. 1841. After a gap of more than two decades, four other railways made their entry, all within the space of two years. The two stations on the north side of the City were Broad Street, North London Railway, in November, 1865, and Moorgate Street, Metropolitan Railway, 21 month later.

Approach from the south involved bridging the River Thames, a task which had not been undertaken by any railway in the neighbourhood of the Metropolis until this period. The London. Chatham & Dover Railway opened its bridge at Blackfriars on December 2l, 1864. to reach its original terminus at Ludgate Hill, a station which formed the subject of an article in The Railway Magazine for December, 1964. The South Eastern Railway, then engaged in keen competition, reached Cannon Street less than two years later.

Earlier, but unsuccessful, schemes for railways entering the City had been promoted in the 1840s, usually in conjunction with proposed new streets. The north bank of the River Thames offered an attractive route, of course, long before the construction of the Victoria Embankment. In 1841 Major-General Sir Frederick Trench advocated such an embankment, between Hungerford Market (afterwards the site of Charing Cross main-line station) and Blackfriars Bridge, with a cable operated elevated railway carried on columns above the roadway. This scheme was outlined by Mr. J. Spencer Gilks in an article in The Railway Magazine for July, 1961. A complementary scheme was the Thames Embankment & Railway Junction Company, which included a proposed new “railway street” from Blackfriars Bridge to the station of the Blackwall Railway (Fenchurch Street) consisting of an elevated railway over a new road. This would have served the area of the present Cannon Street Station, but on an eastwest route.

The City of London Junction Railway, one of the many “grand central station” schemes, would have built its central station on a site bounded by Moorgate Street, London Wall, Throgmorton Street, and Lothbury. This also included approach from the south by an iron bridge over the Thames near the site of the present Cannon Street railway bridge. None of these schemes proceeded beyond the paper stage.

The line which eventually reached Cannon Street was a branch of the Charing Cross Railway Company. This undertaking was promoted as an independent company, but with the active backing and financial support of the South Eastern Railway, and received its Act of incorporation on August 8, 1859. The 60-chain branch line to Cannon Street, involving another bridge over the Thames, was authorised on June 28, 1861. At this time neither the Victoria Embankment nor the District Railway had been authorised, and the railway authorities envisaged a heavy urban passenger traffic between Cannon Street and Charing Cross. By an Act of July 13, 1863, the South Eastern Railway was empowered to absorb the Charing Cross undertaking by agreement, which was duly done as from August 1, 1864, and the Charing Cross company was dissolved.

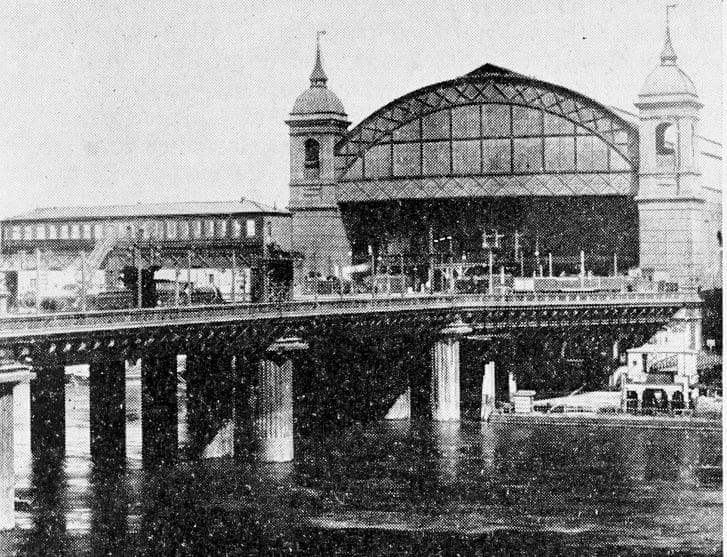

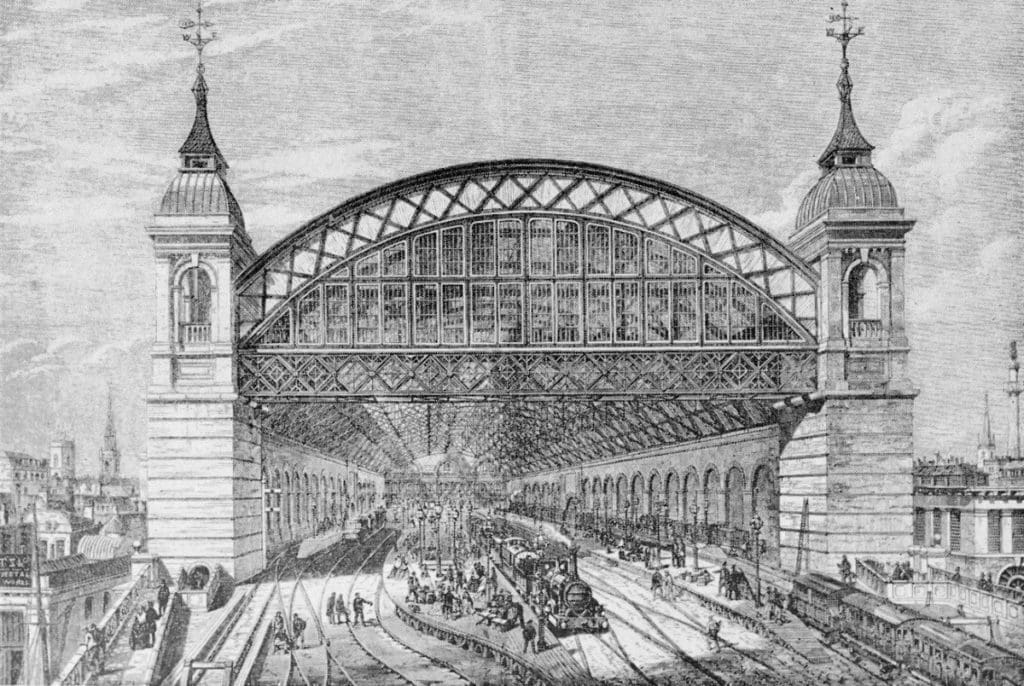

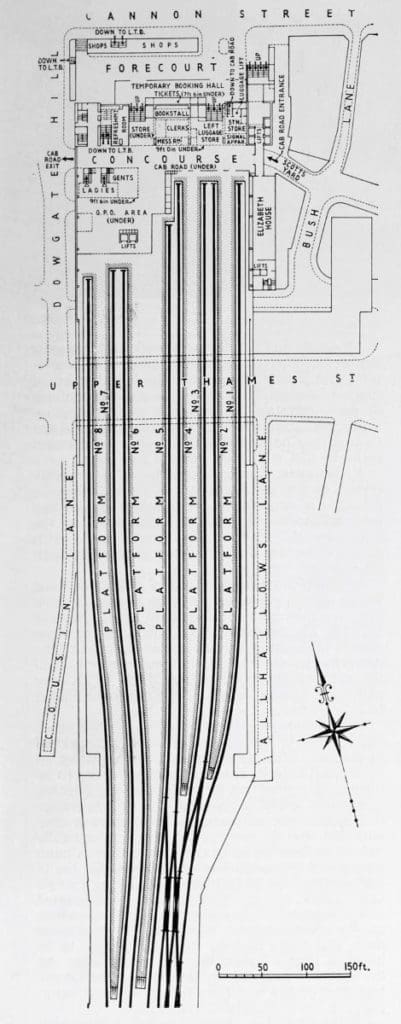

For both the station and the approach bridge over the Thames, the engineer was Sir John Hawkshaw, who had been responsible for Charing Cross bridge. Because of the clearances required for the river bridge, Cannon Street Station was built on arches, which it was envisaged would form valuable lettings if not required for railway purposes. The “cellarage” amounted to 140,000 sq. ft., and no fewer than 27-million bricks were used. From the public highway in Cannon Street to the northern end of the bridge the distance was 855 ft., of which the forecourt occupied 90 ft., the booking office 85 ft., and the platforms and circulating area 680 ft. The width of the station was 201 ft. 8in. outside the walls, and 187 ft. inside at platform level.

Exclusive of the forecourt, the area of the station was 152,632 sq. ft. It accommodated nine lines of rails at what were described as five platforms, treating island platforms as units, and ignoring the available faces. The whole was covered by a single-arch roof standing on side walls rising 45 ft. above platform level and reaching a height of 120 ft. This comprised an area of four acres of which two acres were glazed. The river frontage had at the corners bold ornamental towers designed to contain water tanks. The cost of the station buildings and platforms was £157,262.

The bridge is of five spans, of which the two shore spans are 130 ft. each from the face of the shore abutments to the centre of the adjacent pier. There are four such piers of cast-iron columns in the river, at 147 ft. 6in. distance, centre to centre. The columns are of 18-ft. dia. at the base and 12-ft. dia. above low water mark. In all, 16 cylinders were involved, with a total weight of iron of about 10,500 tons. The superstructure consists of free-span plate girders in the two shore openings and continuous plate girders 442 ft. 6 in. long over the three middle spans. The original cost of the bridge was £193,000.

More than half a century later, Mr. George Ellson told the Institution of Civil Engineers that very careful observations had failed to reveal any sign of settlement having taken place in the piers. He was then (1921) describing a strengthening programme which had been effected over 4 1/2 years during 1909 to 1913 at a cost of £99,000.

The original width of the bridge was 66ft. 8 in. and accommodated five sets of rails. At first there was a narrow footway on each side of the bridge, but apparently not available to the public. Colonel Yolland made the formal Board of Trade inspection of the branch and station in July, 1866, and it was announced that the line would be opened on September 1. The Railway Times commented: “The opening is judiciously delayed until after the next half-yearly meeting of the company, so that nothing may be said in respect to traffic, or the hopelessness of the receipts doing more than pay working expenses.” Cannon Street Station was duly opened on Saturday, September 1, and practically all trains went into, and out of, it on their way between London Bridge and Charing Cross. In 1866 seven bogie tank engines were built at a cost of £16,800 especially to work the traffic between Cannon Street and Charing Cross.

Just before the opening, The Times stated that “since the inspection by the Government inspector, the staff of the line has been indefatigable in its exertions to secure the safe working of this important extension. For the past fortnight Mr. Knight has been busily engaged in revising the signals and making all the necessary arrangements for the large traffic expected to pour over the line.” The original signalling, as at Charing Cross, was by Saxby & Farmer, but Cannon Street provided far more complex problems by reason of the confiicting movements at the south end of the bridge. The signalbox, containing 67 levers, was outside the station on the bridge, on a gantry spanning the whole width of the bridge.

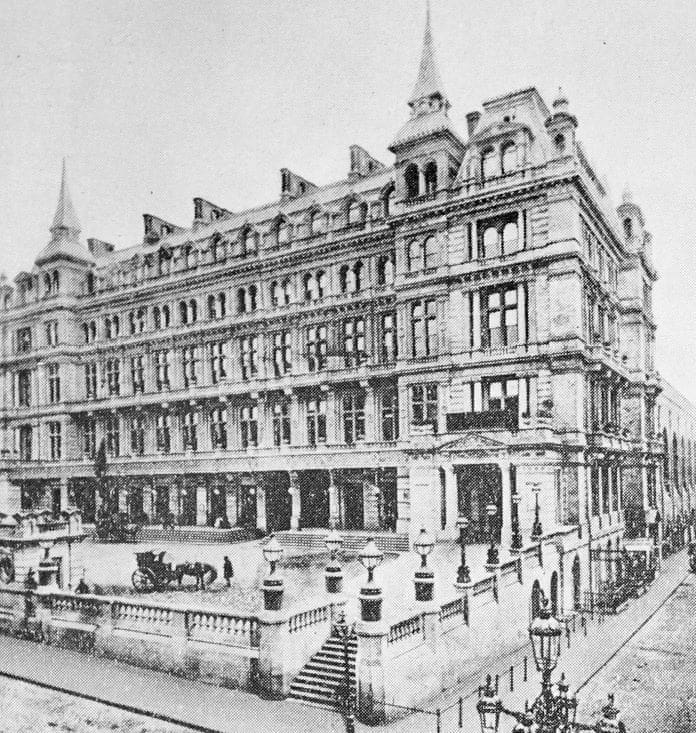

When first opened, 264 trains arrived at, and 261 trains departed from, Cannon Street every day, but these, of course, were “wayside station” rather than terminal station figures. The daily average number of passengers using the station in 1866 was 26,000. The City Terminus Hotel, a five-storey structure which provided the once familiar frontage to Cannon Street Station, was designed by Edward M. Barry, and provided by an independent company. It was opened in May, 1867, and cost about £100,000. Subsequently, it was taken over by the South Eastern Railway.

A public footway with a halfpenny toll was opened across Cannon Street railway bridge in February, 1872, extending from Dowgate Hill on the north side to Clink Street on the south. The entrances were open from 5 a.m. to 9p.m. This was described in the South London Press of February 17, 1872, as “a rival to the footway tunnel under the Thames from the Tower to Southwark.” That tunnel had been built as a tube railway. and was worked for a few months in 1870 with a cable-operated car. On December 24. 1870, this tunnel opened to foot passengers at a halfpenny toll, and served in this capacity for about a quarter of a century, until the opening of Tower Bridge on June 30, 1894, rendered the subway obsolete. The Cannon Street railway bridge was freed from toll about July 12, 1877, the date on which the Metropolis Toll Bridges Act received the Royal Assent. This Act authorised the Metropolitan Board of Works to purchase the toll rights, but also left the South Eastern Railway with the option of closing the footway, which it did shortly afterwards.

Two years before Cannon Street Station was opened, the Metropolitan District Railway had been granted powers to build the south side of the Inner Circle, including a station under the forecourt of Cannon Street. The District Line was brought into use from Westminster Bridge to Blackfriars on May 30, 1870, and extended to Mansion House on July 3, 1871. On the latter date the District Railway (heretofore worked by the Metropolitan Railway) took over the operation of its own railway, under the guidance of James Staats Forbes, who was also a director and general manager of the L.C.D.R. Sir Edward Watkin had become Chairman of the S.E.R. in 1866, and the men were known to be keen opponents. Watkin succeeded in delaying the completion of the Inner Circle until October 6, 1884, on which date Cannon Street underground station was opened. One reaction was that increased efforts were made by the S.E.R. to retain its local Cannon Street to Charing Cross traffic, advertising immediately alongside the underground station: “South Eastern Railway. Open air route. Frequent trains to Waterloo and Charing Cross at reduced fares.”

Increasing traffic made it necessary to widen the approach bridge over the river, and this work was begun in 1886 on the western (up-stream) side. The enlarged bridge, with ten roads, was brought into use on February 13, 1892, increasing the width to about 120 ft., but all the work was not completed until the first half of 1893. It was (and is) carried on piers of six cast-iron columns, of which the four downstream are the originals of 1865, and the two upstream those of the widening. In the 1890s, Cannon Street was claimed to be the widest railway bridge in the world.

Shortly afterwards, new signalboxes were installed, and were brought into use on April 22, 1893. The new signalling was of the Sykes lock-and-block form, similar to that installed at Charing Cross in February, 1888, after that bridge had been widened. Cannon Street was controlled mainly from No. 1 signalbox, erected on the bridge itself and spanning all tracks, with the co-operation of No. 2 box at the south-west end of the bridge. The elevated No. 1 box ranked for many years as one of the most remarkable in the country, and for a considerable period its total of 243 manual levers held the distinction of being the largest number accommodated in one cabin.

After many years of fierce competition, the undertaking of the S.E.R. was, by arrangement, joined with that of the L.C.D.R. on January 1. 1899, for united working under a Managing Committee. The arrangement was confirmed and sanctioned by Parliament under an Act of August 5, 1899. In May, 1900, it was stated that the total number of trains entering Cannon Street daily was 398, and that departing was 385. The Financial Times commented: “Bearing in mind the manner in which they get in each other’s way at the triangles [presumably meaning Cannon Street South and Borough Market junctions at the south end of the bridge], the work of handling them without accident seems to call for superhuman qualities on the part of those who direct the traffic.” Eventually, the practice of Charing Cross trains running via Cannon Street ceased on the night of December 31, 1916, after having applied for fifty years.

In 1918, as a wartime expedient, Cannon Street was closed to passengers during the middle of the day, and on Saturday afternoons and Sundays. This enabled it to be used for the transfer of goods trains from the Midland and Great Northern lines, which came through the Metropolitan Widened Lines and Ludgate Hill, and reached the South Eastern by means of a spur connection between Blackfriars Junction and Metropolitan Junction, which had been opened on June 1, 1878. Considerable traffic improvements were made by the systematic scheduling of trains on a “parallel” basis, a plan which was adopted on Monday, February 13, 1922, for the up morning trains, and extended to down evening services in July. No track alteration or signalling changes were needed.

The basic principle was scheduling trains so that (1) at junction points, up and down trains on the same routes passed at the same times, thus avoiding conflicting movements because of route divergence or confluence; and (2) where multiple tracks were available, trains were scheduled to run parallel, and directed so that not only two up but also two down trains would be given simultaneous non-conflicting paths. By scheduling two up trains to leave platforms 1 and 4 at London Bridge for Cannon Street, they could both be given clear parallel paths through Borough Market Junction. Meanwhile, two down trains from Cannon Street were scheduled to pass that junction at approximately the same time as the two up trains. This was further carried out by routing the trains to or from platforms at Cannon Street so that all four had clear paths between London Bridge and Cannon Street. Between these sets of four trains, two Charing Cross trains were dealt with. Thus, an up train from No. 2 platform at London Bridge was able to diverge at Borough Market Junction, and at the same time a down train from Charing Cross pass, and thus avoid any conflict with either up trains to or down trains from Cannon Street.

Although schemes for extensive suburban electrification were prepared by the South Eastern & Chatham management shortly after the first world war, no work was undertaken until after the Southern Railway came into being on January 1, 1923, as the “amalgamated company” of the Southern Group under the Railways Act, 1921. The first electric working from Cannon Street was begun on February 28, 1926, and consisted of the services to Orpington, Bromley North, and Addiscombe and Hayes. This was regarded as temporary electrification, because it was found to be essential to re-lay the whole of the complex track connections on Cannon Street railway bridge and also to remodel the station layout and install new signalling before the full value of electrification could be secured. This reconstruction did not lend itself to piecemeal methods. and the operation was a major exercise in planning.

An entirely new track layout was prepared, and assembled in a field alongside the goods yard adjoining New Cross Gate Station before being transferred in sections and placed in position on the bridge at Cannon Street. Some associated work had already been put in hand, including replacing and strengthening bridge girders where the new tracks would be in positions different from those occupied by the old lines. It was, of course, by no means unusual for a section of track to be assembled with a view to replacing an existing one by a completely built-up section, but the present writer stated some forty years ago, in describing the work, “so far as we can call to mind, there has been no previous instance of this being done on so large a scale, in that the new layout represents a total length of approximately 1,000 ft. and then does not cover the Cannon Street platform sections nor the connecting portions at Borough Market Junction.”

Cannon Street Station was closed from 3 p.m. on Saturday, June 5, 1926, and about 1,000 men, 750 of whom worked in three shifts, were employed in removing the old platforms, lines, and signalling, and installing the new. The old layout of nine platform; (of which No. 4 was a short bay) was replaced by eight platforms ranging from 567 ft. to 752 ft. in length with a minimum width of 20ft. The old platforms were numbered from west to east, but the new ones were numbered from east to west. The work was completed to schedule and Cannon Street was reopened at 4 a.m. on Monday, June 28, with the arrival of an electric train. Initially, platforms 1 to 5 were equipped for electric traction, leaving the remainder for main-line steam-operated services. Platforms 6 and 7 were electrified in connection with the Gillingham and Maidstone electrification scheme which was brought into service on July 2, 1939.

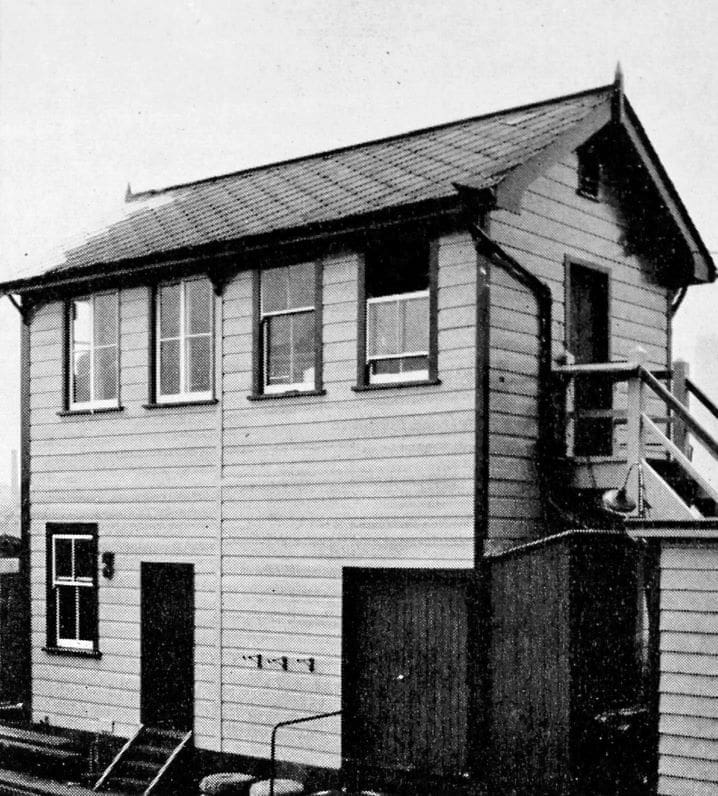

Four-aspect colour-light signalling was brought into use on Sunday, June 27, I926, from Charing Cross and Cannon Street to Borough Market Junction, but there were no public trains to or from Cannon Street until the next morning. The new Cannon Street Station signalbox was located on the river bridge adjacent to No. 8 platform, and, as it was power-operated, was much smaller and more convenient than the one it replaced. Its 143-lever frame was housed in a structure 45 ft. long by 12ft. wide. Temporary restricted train services ran from Cannon Street at first, and it was intended to begin full working on July 11. but in fact the full service was not introduced until July 19, 1936.

As remodelled in 1926, equipped for suburban electric traction on platforms 1 to 5, and with four-aspect colour-light signalling installed. Cannon Street handled a weekday peak-hour traffic of increasing intensity, and also accommodated both main-line trains and non-electrified suburban services with steam traction. It was reopened on Sundays from July 6, 1930. A few trains resumed running into and out of Cannon Street on the way from Charing Cross to London Bridge from July 17. 1933, but this never again became a widespread practice as it had been from 1866 to 1916, and indeed the remodelled layout of the junctions south of the bridge would have precluded it. Eight years before the second world war the hotel was closed. and converted into an office building called Southern House, but the public rooms continued to be used for banquets and company meetings.

It has been recorded already that platforms 6 and 7 were electrified in connection with the Gillingham and Maidstone electrification which was brought into service on July 2, 1939. Only two months later, on September 3, the second world war began, but the Southern Railway Chairman said in March, 1940, that a considerable increase in traffic had resulted from electric traction even in these first two months. Then emergency passenger services came into force from October 16, 1939. Cannon Street was closed on Sundays and from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. and after 7.30 p.m. on weekdays. This applied throughout the war and until after railway nationalisation.

In the famous fire raid of December 29, 1940. which devastated a substantial part of the City of London, Cannon Street Station was hit by incendiary bombs, but these were extinguished successfully. Its heaviest air raid damage was in the night of May 10-11, 1941. another of the noteworthy London blitz dates. Two heavy high-explosive bombs fell by the side of one of the platforms: the station hotel building caught lire and was ultimately gutted; and the station roof received severe tire damage. Trains standing in the station were taken out on the bridge. but this also suffered from both bombs and fire. In the morning, Cannon Street was one of five London terminals of the Southern Railway which were temporarily closed.

Cannon Street Station emerged from the war with both short-term and long-term problems. The top two floors of Southern House (the old hotel building) were rebuilt following fire damage. The station roof glazing had been removed for safety, and an examination of the roof structure in 1948 showed that it could not then carry new glazing, but could probably support its own weight for a further ten years. The long-term problems were provided by the vast post-war increase in London suburban passenger traffic, the greater proportion of which has been on the southern and eastern approaches to the City. With railway nationalisation under the Act of August 6, 1947, the solution of these problems became the task of the British Transport Commission, which assumed ownership on January 1, 1948. The Eastern Region handled the traffic increase by electrifying its suburban lines into Liverpool Street and Fenchurch Street, and also was assisted by the extension of the Central Line of London Transport into Essex.

The Southern Railway had already brought its line capacity near to saturation point by electrification before 1939, and it received no help from London Transport extensions. From May 31, 1948, Cannon Street was reopened in the middle of the day on weekdays, and reopened on Sundays from October 3, but this did not alleviate the peak—hour problem. Experimental use was made of two-level (or double-deck) multiple-unit electric trains, the first of which went into service on November 2, 1949. Seats in the compartments were arranged on two levels, but there were no separate decks. This experiment proved unsuccessful because of increased time taken in loading and unloading. In 1950 it was decided to increase the length of trains from eight to ten coaches, and in 1956 to 12 coaches.

Because of serious shortage of technical staff, the Southern Region commissioned Messrs. Freeman, Fox & Partners in 1953 to prepare schemes for lengthening the platforms at Cannon Street and for replacing the roof. To lengthen the platforms at the river bridge end proved impracticable from the operating viewpoint, as it would leave insufficient distance between the longer platforms and Borough Market Junction. It therefore became necessary to lengthen the platforms at the concourse end and to provide a replacement concourse area under Southern House. This proved possible as a short-term expedient, but serious structural defects discovered in some wrought-iron girders supporting Southern House necessitated a change in long-term plan. Eventually it was decided to undertake complete commercial redevelopment of the northern part of the station site, demolishing Southern House and replacing it by a new building, and also erecting another office block on a new site in Bush Lane, alongside the station, which was acquired from the Drapers Company.

As the ten-car scheme was due to be introduced in March, 1957, there was no time to be lost in lengthening the platforms. Work was begun in November, 1955, when the booking office and bookstall were transferred to a temporary building in the forecourt. Five of the lengthened platforms were brought into service on March 4, 1957, enabling 22 ten-coach peak—hour trains to arrive in the morning and 23 to leave in the evening.

Early in the morning of April 5, 1957, fire was discovered in Cannon Street Signalbox. Although the first appliances arrived in four minutes, the box was burned out. The cause could not be determined, but was probably a cable fault. Hand signalling was set up and a skeleton suburban service began on April 8. Platforms 7 and 8 were closed, and 5 and 6 extended temporarily to take 12-car trains. Main-line steam trains were diverted to Holborn Viaduct, Charing Cross, and Victoria. Special buses were run between Cannon Street and London Bridge stations. On the day of the fire. the London Midland Region offered to supply a 225-lever power frame which was in store at Crewe. The Southern gladly accepted this offer, and the frame was dispatched by special train to the signal works at Wimbledon the same day. Part was made into a 47-lever frame, installed in the reconditioned staff rooms of the Cannon Street box and brought into use on May 5, enabling six of the eight platforms to be used. From the next day a full electric suburban service ran. Most main-line trains continued to use other termini. From May 6. also. two multiple-unit diesel-electric trains were introduced prematurely on the Cannon Street-Hastings service via Tunbridge Wells Central.

Although temporary arrangements still obtained at Cannon Street. the full “ten-car scheme” for peak-hour suburban trains came into force with the summer service on June 17, 1957. Platforms 5 and 6, and 7 and 8, were extended southward in permanent construction in January, 1958, to give the platform layout as it now is.

Early in 1957 plans were prepared for the demolition of the high-level roofing, with the assistance of a movable gantry which had been used to demolish the roof of New Street Station, Birmingham. A contract was awarded in December, and work on site was begun on April 10, 1958. To facilitate the work, the station was closed for some weeks during the midday period, and on Saturday afternoons and Sundays. The demolition of the roof was completed in January, 1959. More than 1,000 tons of metal was removed and sold as scrap. Numerous schemes were proposed in connection with the new roofing. Requests were made by various Ministries and public authorities, including reduction of the height of the side walls to improve the view of St. Paul’s Cathedral; provision of a roof car park with spiral access; and accommodation for a heliport. None of these works has yet been undertaken. In addition, the City Corporation proposed to widen Upper Thames Street, which the railway spans on a bridge. This was duly done and the new bridge consisting of 85-ft. span twin box girders for each track, was completed in December. 1964.

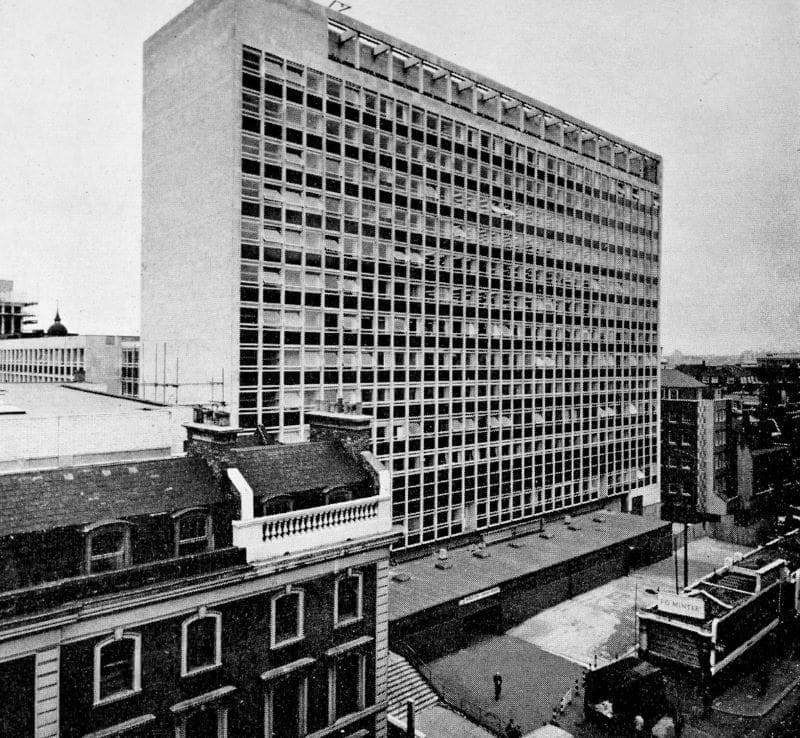

After the decision was taken to demolish Southern House, various plans were considered for the commercial development of the whole northern part of the station site. A scheme for a 9-storey main office block. 220 ft. high, was rejected by the planning authorities in July, 1958. A revised scheme received planning approval in 1959, but the arrangements were later modified because of the increasing cost of building and also the severe restrictions on office development. The main feature of the development works now approaching completion is a 15-floor office building replacing the old Southern House. This has been undertaken by British Railways in conjunction with City Properties (Cannon Street) Limited, a subsidiary of Town & City Properties Limited. In front of this building, on the forecourt, it was proposed to erect a low structure containing shops and two storeys of offices, but this has not yet been done.

In addition to the block on the Bush Lane site, the revised plans included a podium block on the east side of the station, extending over the northern part of platforms 1 to 5, with a flat slab roof over the remaining platforms 6 to 8. Work was begun in 1960 on the Bush Lane block, following the demolition of part of the station side walls, and, towards the end of the year, piling for the roof and podium block foundation. The Bush Lane block was completed and occupied in February, 1962, and the podium block later in that year. It was found that there was no necessity to extend the overall roof farther south than the podium block, and, for reasons of economy, the decision was taken to provide only umbrella roofing for the platforms.

Fifteen-storey frontage

Demolition of Southern House was begun in January, 1963, and completed in July. To facilitate this, and to avoid the risk of passengers being hit by falling rubble, the whole of the circulating area in the forecourt, and the concourse under Southern House, were closed for passengers on April 20, and on the next day two temporary exit-entrances were opened. The station was virtually divided into two, as there was very little room for walking from one side to the other. The suburban platforms 1 to 4 were serviced from the east side, with approaches from both Cannon Street and Bush Lane; access to platforms 5 to 8 was provided on the west (Dowgate Hill) side, along a covered way. Piling for the new 15-storey building was taken in hand in August, 1963, and completed in October, when steelwork erection was begun. It is a steel-framed structure to the fourth floor and the remaining eleven floors were built on the American lift—slab principle. The block is about 220 ft. long, 50 ft. wide, and 170 ft. high. It was ready for occupation at the beginning of July, 1965. Station facilities and railway offices are on the ground, first, and second floors. The remainder of the building has been leased to Lloyds Bank for use as a computer centre, and this was opened on May 9, 1966.

A new temporary booking office, using cash registers, was opened on Monday, December 13, 1965. The front of the office is covered with armoured glass protected by stainless-steel shutters. Although much progress has been made, the approach to the station from Cannon Street does less than justice to what has been called “London’s first big rail terminal of the sixties”. The work remaining to be done is largely in the forecourt area, where the situation is complicated by the presence of the London Transport station. The City Corporation wishes to widen Cannon Street and move the building line back some 15 ft. This would entail complete reconstruction of the London Transport sub-surface booking hall, with costly re-girdering. Until this is resolved, the approach in unlikely to be improved. At the beginning of its second century, all that remains of the old station are the twin towers (the subject of controversy as to their possible retention on architectural merit) and part of the side walls.