Hornby’s decision to recreate in OO scale some of Britain’s most famous one-off locomotives, including Gresley’s W1 4-6-4 and now Stanier’s geared turbine Pacific No. 6202, leads Pete Kelly to chart the history of the Turbomotive, with the help of some interesting archive photographs.

William Stanier’s contribution to the LMS could not have been forged in a better place than the GWR’s Swindon Works where, as principal assistant to Chief Mechanical Engineer Charles Collett, his work had concentrated on the steady refinement of the GWR’s well-proven fleet of advanced and efficient standard locomotive designs.

While the Grouping of January 1, 1923 hardly altered the GWR at all, the LMS – by far the biggest of the ‘big four’ companies – inherited a huge and ill-assorted legacy of locomotive stock, and an intense rivalry between Derby and Crewe did little to facilitate the massive shake-up that was needed from the start.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

A succession of CMEs including George Hughes, of the former Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway, and Sir Henry Fowler, of the former Midland Railway, made important contributions to the newly-formed company, but these were never enough to satisfy the seismic changes in both locomotive stock and workshop practices that were called for.

That shake-up came on January 1, 1932, when Stanier was head-hunted to succeed Sir Ernest Lemon and at long last take on the massive challenge that still lay before the LMS, which needed above all a range of modern, standardised locomotive classes covering the entire field of operations.

In order to compete effectively with the rival LNER and its comparatively easy East Coast Main Line route, a priority was to establish more powerful express passenger locomotives, along with huge numbers of modern mixed traffic and heavy freight types with wide route availabilities.

While Fowler’s three-cylinder parallel-boiler Royal Scot 4-6-0s had been putting up some excellent performances on the West Coast Main Line with trains of 400 tons plus, engine changes were still required on long runs. The much heavier trains and straight-through workings to come would require large four-cylinder Pacifics, and Stanier was authorised to design the first three locomotives of a class that became known as the Princess Royals.

Stanier was a sound, practical engineer whose work had always revolved around well-proven principles. When the first two locomotives emerged from Crewe Works in 1933, the cylinders of Nos. 6200 The Princess Royal and 6201 Princess Elizabeth had exactly the same 16¼ x 28in dimensions as those on Collett’s King 4-6-0s, along with the same driving wheel diameters of 6ft 6in.

Even the tractive effort figures were all but identical, but there the similarities ended, because the Princess Royals would have to work under very different conditions from those on the GWR.

Against this background, it must have come as quite a surprise when, after visiting Sweden to evaluate the performance of a Ljungstrom steam turbine locomotive, Stanier’s third intended Princess Royal, No 6202, turned out to be a unique geared turbine locomotive that would become known as the Turbomotive.

It finally emerged in this a guise in 1935, the same year as the remaining 10 Princess Royals, although unlike them it remained nameless until it was finally rebuilt in conventional form in 1952.

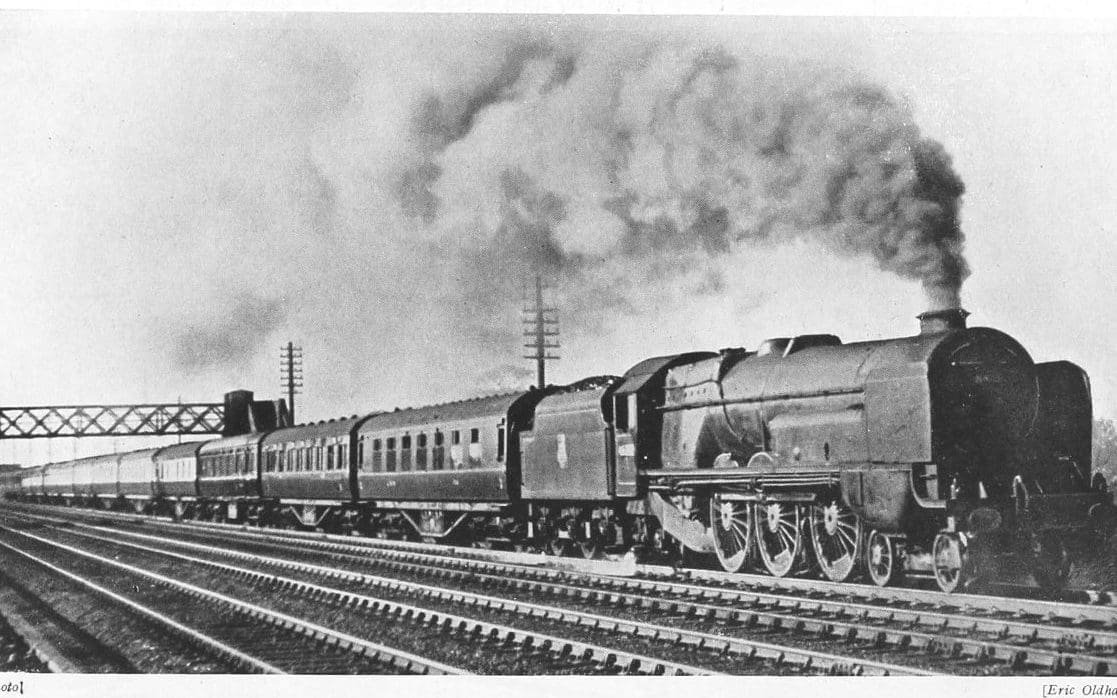

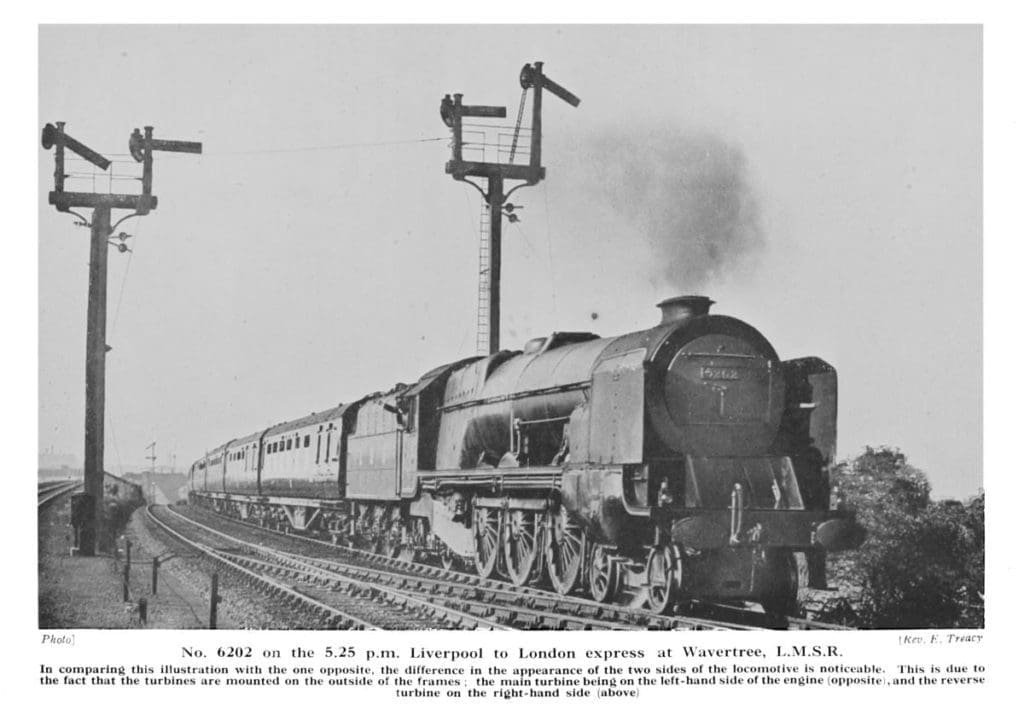

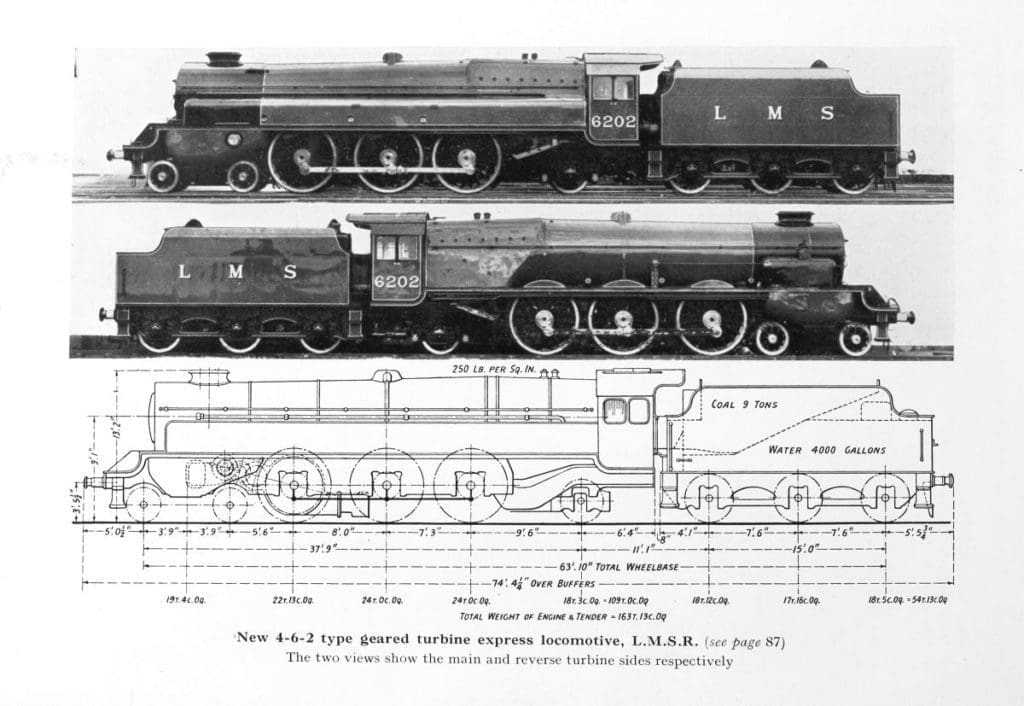

Britain’s giant engineering firm Metropolitan Vickers, which shared an interest in turbine power and had also visited Sweden to study the Ljungstrom Pacific, duly won the contract to supply the turbine equipment. The Turbomotive featured two separate turbines – a large forward one with 18 rows of blading housed in a casing that ran the entire length of the left-hand side, giving the locomotive a clean and handsome appearance, and producing 2400hp at just over 7000rpm at a steam pressure of 250lb.

The much shorter reverse turbine, consisting of just four rows of blades, was situated at the front on the right-hand side and gave the Turbomotive a more broken-up look. Although the reverse turbine was meant to be used only when the locomotive was running light engine, or perhaps engaged in some very light shunting, it proved troublesome when these limitations were exceeded, and repairs inevitably resulted in longer and more expensive works visits than would have been the case with conventional locomotives.

The beauty of steam turbine power, which was already in common use in shipping, was of course its utter smoothness. During the 1960s I often travelled to the Isle of Man and back on the Steam Packet Company’s fleet of fast and smooth turbine vessels, and when they were eventually superseded by diesel-powered ships, I found the constant thumping of the engines irritating to say the least!

Stanier’s turbine-driven Pacific proved one of the more successful experimental steam locomotives to run in Britain, spending much of its life operating heavy express trains between Euston and Liverpool Lime Street. The large forward turbine was in use for the vast majority of its active life. Before the smaller turbine could be brought into use, the Turbomotive had to be at a standstill, and when the switch was made by means of a dog clutch, the steam supply to the main turbine was cut off.

The completely even torque on the Turbomotive’s driving axle eliminated the ‘hammer blow’ of many conventional reciprocating locomotives at a stroke, and No. 6202 also proved more economical on coal. It must have been interesting to see it rushing by with simply a whine and, rather than the expected sharp exhaust blasts of a conventional locomotive, a continuous exhaust stream from its double chimney.

The absence of conventional cylinders and valves meant that the connecting rods had the simplest of appearance as they spread the drive from the front axle to the two behind it.

Power output was controlled by six nozzles that could be individually opened or closed as required, admitting steam to the turbine, and the Turbomotive became a popular engine with its crews once they became used to its unique control features.

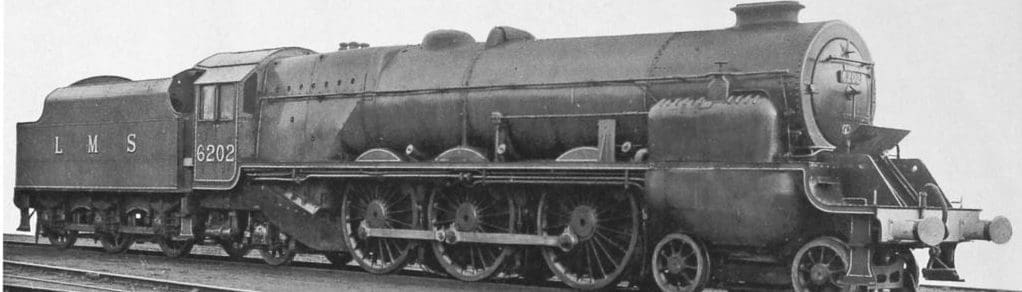

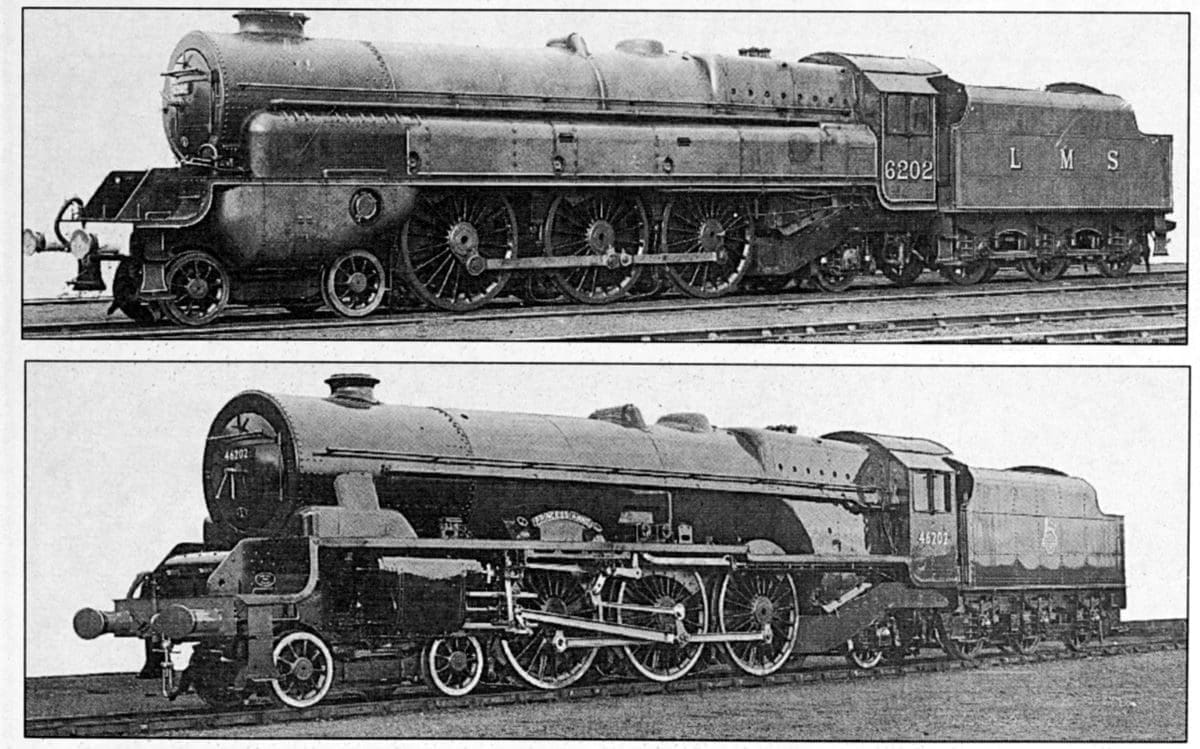

Because of the Turbomotive’s low-pressure exhaust, a special double blastpipe and chimney was fitted, but in certain conditions smoke drift could still be a problem and led to the fitting of smoke deflectors in 1939. Soon after the outbreak of the Second World War, the locomotive was stored for a while before being reinstated to service in 1942, but when a turbine failure occurred under British Railways in 1949, the repair costs to what had now become No. 46202 were considered uneconomical – particularly during the difficult postwar austerity years. The locomotive was taken out of service once again pending a rebuild into a conventional machine.

Emerging in 1952 as a handsome new Pacific named Princess Anne with new mainframes and a Duchess rather than Princess Royal cylinder arrangement, No. 46202 proved a handsome and immensely powerful hybrid that was officially designated the Princess Anne class.

On the fateful morning of October 8 1952, it had run only 11,443 miles when, piloted by Jubilee 4-6-0 No. 45637 Windward Islands on the 8am Euston to Liverpool and Manchester train and travelling at 60mph, it ran into wreckage that had been strewn across the track at Harrow and Wealdstone station moments after Duchess Pacific No. 46242 City of Glasgow, heading an overnight train from Perth, collided with the back of a stationary Euston-bound commuter train at speed.

It had passed a colour light signal at caution and two semaphore signals at danger.

The 112 people killed in the horrific multiple collision included the driver and fireman of City of Glasgow and the driver of Windward Islands.

The two locomotives heading the northbound train were deflected to the left and scythed diagonally across a platform before landing on their sides on the adjacent DC line.

The Jubilee was written off completely and Princess Anne was so badly damaged that it would never run again, although its boiler was repaired and reused. The urgent demand for Class 8P motive power remained, however, and resulted in the construction of the unique three-cylinder BR Standard Class 8 Pacific No. 71000 Duke of Gloucester in the year 1954.

The models

Hornby’s forthcoming OO scale models will represent the Turbomotive in both original LMS condition (R 30134 and R 30134X) and its short-lived British Railways service in lined black livery with smoke deflectors (R 30135 and R 30135X). The X versions will be DCC-fitted with 21-pin sockets, and it will be interesting to see what kind of sound effects will be suitable for what was in real life such a whisper-quiet locomotive.

Comparing the high-resolution images of the models with our archive photos shows up an absence of some riveted detail – but some of it is there, beneath the smooth paint finish, with very neatly applied lining, cab-side power classification details and locomotive numbers.

The overall lines of the locomotives are captured well, and the BR lined black version with smoke deflectors will be of particular interest to many modellers, for the Turbomotive ran in that condition for less than two years before a final costly turbine failure brought the decision to rebuild it as a hybrid between a Princess Royal and a Duchess.

The high-resolution photograph of the main turbine side shows the long casing to be plain black, with red lining on what can be seen of the boiler bands, with more fully-applied lining along the running plate, around the cab-side numbers and on the tender sides.

Hornby has announced prices of £266.49 for the basic specifications and £290.49 for each of the X versions.

Advert

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.