Words: Robin Jones/Heritage Railway magazine

This year the Bluebell Railway was due to celebrate six decades since the first green shoots of one of the world’s most popular and successful heritage lines appeared.

Sadly, the showpiece anniversary celebrations have been placed on hold due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the railway, for so long a household word for classic steam, is now like the rest of the heritage sector fighting a battle for survival, having launched a nationwide emergency appeal for vital funds just to stay afloat, writes Robin Jones.

May 14, 1951, marked the dawn of a dynamic new era, for it was on that day that the Talyllyn Railway began running services using volunteer labour, marking the start of the British operational heritage railway sector.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Two years later, the hit Ealing comedy The Titfield Thunderbolt, the first film shot in Technicolor and inspired by the exploits of the Talyllyn Railway Society, told the story of the villagers trying to stop their local branch line from being closed, and brought the basic concept of volunteer-led railway revival into the public consciousness big time.

On July 23, 1955, the Ffestiniog Railway, under the guidance of the late Alan Pegler, ran its first heritage era train.

June 1960 saw the Middleton Railway, a private freight-only concern that had operated continuously since 1758, become the first standard gauge railway to be taken over and operated by unpaid volunteers, with students from Leeds University under the guidance of their lecturer, the late Dr Fred Youell, running trains for a week using a diesel locomotive to haul a redundant Swansea & Mumbles Railway tramcar.

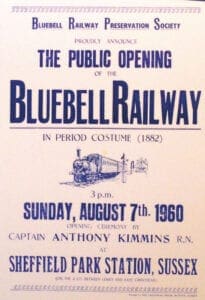

However, the biggest breakthrough to date came on August 7 that year, when Bluebell Railway volunteers ran the first train on a revived section of the British Railways standard gauge national network – paving the way not only for other ‘Premier League’ lines to follow, but setting world-leading standards in the field of railway heritage.

Indeed, had the UK heritage railway movement taken several more years to reach that stage, how many now-priceless examples of classic locomotives and rolling stock would have been lost forever?

The Bluebell laid down a blueprint for rail revival, but not necessarily one for plain sailing: indeed it was to be another eight years before the next former BR line to be reopened as a heritage line, the Keighley & Worth Valley Railway, would run its public trains.

The market-leading heritage line has its origins in the 1877 Act of Parliament which authorised the building of the Lewes & East Grinstead Railway, which was acquired by operator the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway under subsequent legislation a year later. Both Acts included a clause that “Four passenger trains each way daily to run on this line, with through connections at East Grinstead to London and to stop at Sheffield Bridges, Newick and West Hoathly.”

The clause imposed a statutory requirement to provide a service – and the only way to remove this obligation was to pass another Act.

In 1954, British Railways’ branch line committee proposed closing the line from East Grinstead to Culver Junction near Lewes. Despite a challenge by local residents, the closure date was set for June 15, 1955, although it took place earlier, on May 29, due to a rail strike.

Local residents were determined not to take it lightly, and battled for the next three years to get the decision reversed. Shortly after closure, Chailey woman Margery ‘Madge’ Bessemer, the granddaughter of Henry Bessemer, inventor of the Bessemer converter for converting pig iron into steel, discovered the clause in the 1877 and 1878 Acts relating to the ‘Statutory Line’ and demanded that BR reinstate services.

Aided by local MP Tufton Beamish, she forced BR to rethink. Faced with this statutory legal obligation, on August 7, 1956 BR extremely begrudgingly reopened the line, but with trains stopping only at stations mentioned in the Acts. It was to be done strictly by the book, and not an inch more. Because of this, the reintroduced timetable became nicknamed the ‘sulky service’.

BR took its case to the House of Commons in 1957, resulting in a public inquiry. BR was censured, but later the Transport Commission was able to persuade Parliament to repeal the special section of the Act that has prevented closure, and so the last passenger train ran on March 16, 1958.

It has been said that while picking spring flowers on the embankment near her estate Madge, who loved wildlife, may have herself invented the nickname of the ‘Bluebell Line’. On that final day of services, Madge had a chance encounter with Carshalton Technical College student Chris Campbell, who shared his many recollections of travelling on the line while spending school holidays with relatives. Inspired by her efforts to save the line, Chris, then aged 18, wondered if it might be possible to win a second round with BR.

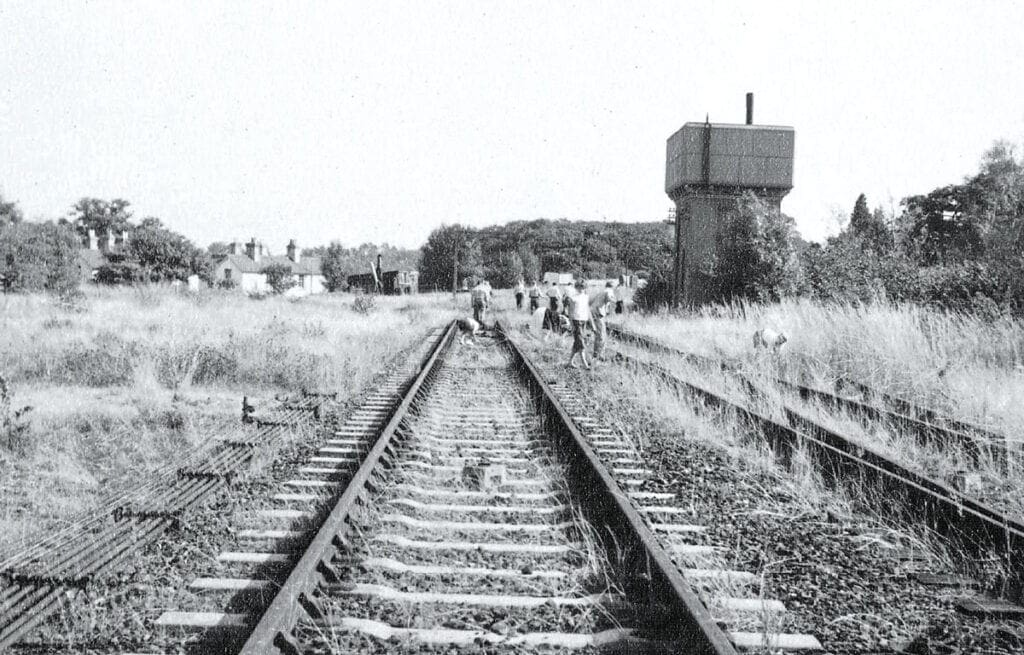

Meanwhile, Martin Eastland, 19, a telecommunications engineering student of Haywards Heath, David Dallimore, a student at the London School of Economics, from Woodingdean, and Brighton-based Alan Sturt, 19, who was studying at the Regent Street Polytechnic, had mooted the idea of setting up a preservation society for the route, drawing on the examples of the abovementioned Welsh narrow gauge lines.

The students wrote to interested parties highlighting Madge’s campaign and the unexpected level of public support that it had created. They initially hoped to save the entire route, reopening it stages at a time, acquiring a GWR railcar for regular passenger services and adding a two-car DMU which funds permitted, but using steam during the summer months when visitors would flock to the ‘sunny south’.

On March 15, 1959 a group that included future society president Bernard Holden, met in Haywards Heath and formed the Lewes and East Grinstead Railway Preservation Society, but then voted to change its name to the Bluebell Railway Preservation Society.

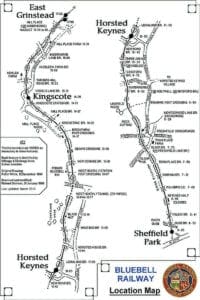

The society’s very over-ambitious initial aim was to reopen the line from East Grinstead to Culver Junction as a commercial service. However, when the society failed to raise the money buy the whole line, it was forced to edit its dreams – an experience which would beset many future revivalist groups. The society then settled for using just the line between Sheffield Park and Horsted Keynes as a tourist attraction, with vintage locomotives and stock operated by unpaid volunteer staff.

As BR still ran the third-rail electrified line from Horsted Keynes to Ardingly and Haywards Heath, the society leased a stretch of track from just south of Horsted Keynes. The electric services came up from Seaford via Haywards Heath and Ardingly to Horsted Keynes. Initially planned to go further north, any extension of the three-rail electrification beyond Horsted Keynes was permanetly halted by the Second World War and never revived.

The revivalists aimed to maintain the LBSCR heritage of the line by using LBSCR locomotives and stock. Their ideal locomotive was a Stroudley D1 0-4-2T, but they found that the last one had been scrapped 18 months previously. Their second choice was a ‘Terrier’ 0-6-0T, and for £750 BR sold them No. 32655 (LBSCR No. 55) Stepney, plus two coaches. A legend was born!

Stepney hauled what was the Bluebell’s first train via Haywards Heath to Horsted Keynes and from there onwards to Sheffield Park on May 17, 1960.

Back in servicer

On August 7 that year, the first Bluebell Railway services proper ran from a temporary stop, Bluebell Halt, 100 yards south of Horsted Keynes, to Sheffield Park.

That first operating season lasted until the end of October, running at weekends only, yet more than 15,000 passengers were carried. Most importantly, the revivalists had shown that a standard gauge steam service using volunteer labour could be viable.

October 29, 1961, saw the Bluebell permitted to work into Horsted Keynes station, even though it was still used for electric services. At first, the Bluebell trains ran into the disused eastern side platform.

In 1962, the society invited none other than BR chairman Dr Richard Beeching to open a second new halt at Holywell (Waterworks). That was in the year before East Grinstead resident Beeching published his infamous Report on the Reshaping of British Railways. Ironically, Holywell (Waterworks) Halt closed within 12 months.

BR withdrew passenger services from Horsted Keynes to Haywards Heath in 1963 and also closed the routes north to East Grinstead and west to Ardingly. Not only did the Bluebell Railway find itself severed from the BR system, but even hired-in North London Railway 0-6-0T No. 58850 and LBSCR E4 0-6-2T No. 473 Birch Grove to the contractors who were ripping up the track north of Horsted Keynes in 1964.

Seeking new horizons

Looking to expand what had by then become a major visitor attraction, in 1975 the society bought the site of the demolished West Hoathly station, to make a start on a push back north and an eventual return to East Grinstead.

Kingscote station was bought in January 1985, and in the face of opposition from local councillors, a public inquiry resulted in both the secretaries of state for the Environment and Transport giving planning permission and a Light Railway Order for an extension to East Grinstead that year.

Work on the six-mile extension from Horsted Keynes to East Grinstead began in March 1988 with a golden spike ceremony. However, it would not be a quick job.

The extension from Horsted Keynes as far as Kingscote was completed in 1994, including the relaying of track through the 731-yard Sharpthorne tunnel, but planning permission was not forthcoming for the rebuilding of West Hoathly station.

BR donated East Grinstead’s spectacular Imberhorne viaduct to the railway in 1992. However, the trackbed had been sold off into numerous portions, all of which had to be bought one by one, a process that was not completed until 2003, from when physical civil engineering activity on the extension beyond Kingscote began.

The biggest blockage of all was the 30ft deep 1600ft long Imberhorne cutting, which after the original line was lifted was used as a landfill site for domestic waste. The rubbish had to be extracted if trains were to pass through again. Test borings established that the 96,000 cubic metres of waste were not toxic, but would cost £5 million to remove. The track north of the tip was relaid to allow it to be taken out by rail to a landfill site to the north of Aylesbury.

BBC News presenter Nick Owen publicly began the waste removal on November 25, 2008, using heavy machinery donated from the High Speed 1 Channel Tunnel Rail Link which had just been completed through Kent. GB Railfreight’s first trial movements of excavated spoil by rail were made in 2009.

The date for the public opening to East Grinstead was set for March 23, 2013, and the first two months of the year saw frantic tracklaying as the wintry weather permitted.

On Friday, March 8, shortly after a GB Railfreight Class 66 made a clandestine late-night run over the extension, the final section of track was formally joined using a white fishplate, with long-serving Bluebell extension catering lady Barbara Watkins tightening the four bolts, bringing the total running length of the line to 11 miles.

A severe last blast of winter on March 23 brought snow to East Grinstead, but it would take more than that to deter the Bluebell battlers, who over the decades had fought far worse… and won. The first public train from East Grinstead was hauled by a trio headed by E4 0-6-2T No. 473, aka Birch Grove, in Southern green livery, followed by blue-liveried SECR P 0-6-0T No. 323 Bluebell and No. 55 Stepney,

The first train north from Sheffield Park was headed by U class 2-6-0 No. 1638 and comprised the breakfast Pullman carrying 144 guests who were served champagne.

Shopping triumph

Despite Arctic blasts, a 45-minute service ran to time, with no engine failing. Many of the passengers alighted at East Grinstead and returned hours later with shopping bags – a sight which with pinpointed accuracy boded well for local traders.

Thursday March 28 saw an eagerly-awaited 12-coach UK Railtours charter from Victoria, headed by Class 66 No. 66739 which had taken its turn on the spoil trains, with two BR blue-liveried Class 73s on the rear. After running through to Sheffield Park, the train was hauled back by the 73s to Horsted Keynes, where No. 66739 was named Bluebell Railway by GB Railfreight managing director Mark Smith.

Present at that ceremony with more reason than most to be justifiably proud of the completion of the extension was the line’s infrastructure director and locomotive driver Chris White, the driving force behind the project. Unpaid volunteer Chris had organised the removal of around 100,000 tons of waste from the cutting at the lowest possible cost, sourced £4 million of vital funding and also led the successful challenge against Railtrack’s plans to sell the reserved station site at East Grinstead to supermarket chain Sainsbury’s for a petrol station.

One day, Chris would be found sifting through mountains of legal paperwork, and the next leading a team of contractors. Society chairman Roy Watts said at the time of the extension’s opening: “Those close to the project will know that there were many, many hours given to planning, execution, and delivery, as well as lots of work to get through the mire of the legislative paperwork. But no one knows this more than Chris White, who probably devoted more time to the project than we appreciate.”

In September 2017, Chris stood down as infrastructure director and handed over to Kevin Beauchamp, former head of infrastructure for High Speed 1, but stayed on the board as safety director. Kevin stood down last year due to personal reasons and Chris took infrastructure back on, and was also assurance director. Since then a new safety director had been appointed.

Chris lost a short battle with cancer on May 12. Yet his legacy is one of the greatest engineering features in the heritage railway sector’s portfolio, one which will be enjoyed by countless generations to come.

The East Grinstead extension, which allows visitors from London to travel to the Bluebell Railway by train, indeed brought a tourist boom to the town. In the first year after steam trains returned to East Grinstead, figures showed that the railway attracted 188,144 visitors compared with 146,224 in 2012. Ticket revenue soared from £1,577,474 in 2012 to £2,294,145 in 2013. In 2019, the railway carried more than 143,000 passengers overall.

East Grinstead tourism manager Simon Kerr said: “All this seems to have been accomplished without any extra pressure on the town’s existing car parking capacity. Most of this extra passenger loading comes from the use of the Network Rail connection from London.”

By 2015, the Bluebell Railway was forced to hire more coaches because of the overwhelming success of the northern extension. Before that extension was opened, 60% of Bluebell trains were formed of four carriages, and only 30% of five or six. It was expected that demand for seats would tail off after the euphoria surrounding the opening to East Grinstead, but the opposite has happened. The railway now needs five or six-car trains through much of the season.

The society today boasts a membership of more than 10,000. It is the governing body of the line and sets the strategy, goals and objectives for the operating company – Bluebell Railway plc, of which it is the majority shareholder with a 75% stake.

Vital to the line’s successful operation is a core of around 50 employed staff supported by and working with an extensive array of more than 700 volunteers – drivers, firemen, guards, booking office clerks, station staff, buffet stewards, shop assistants, museum attendants, guides, tracklayers, lineside maintenance, painters, as well as those working in the carriage and wagon and locomotive works.

Each of the four stations is themed in terms of staff uniform, colour schemes and signage: Sheffield Park in the late 1800s of the LBSCR; Horsted Keynes in the 1930s Southern Railway, Kingscote in the 1950s of British Railways and East Grinstead in the 1960s – Southern.

Grade II listed Horsted Keynes with its five platforms is one of the largest stations on any heritage railway. Despite its long service with the LBSCR, Southern Railway and BR, today’s operations represent the busiest period in its history of the station.

The passing place on days with a multi-train service, it holds major events ranging from being Santa’s temporary home at Christmas to a very popular venue for weddings. Its size makes it an attractive location for film makers – the versatility of the site and age of station buildings making a excellent backdrop for period drama from Victorian times up to the 1960s. It became Downton (of Abbey fame) on numerous occasions as well being used for several scenes in the Poirot detective series.

Well set for the future

Indeed, the entire railway – all of its stations are in effect ‘walk-on sets’ – has been a prime choice for location filming for hundreds of feature films, TV dramas, fashion shoots and music videos for nearly six decades starting with The Innocents in 1961.

The railway has a team to support filming activities, with personnel representing every railway department – filming liaison officers, loco crews, guards, shunters, signalmen, station staff, infrastructure and lineside staff. The filming team also has experience working off-site and was able to take a locomotive in steam and with 10 coaches to King’s Cross for scenes filmed for Wonder Woman (2017).

It was also responsible for operational safety and supervised all train movements during the making of Murder on the Orient Express (also 2017) at Longcross Studios.

Revenues from filming, fashion and advertising shoots plus other corporate activity are an essential part of the cash flow required to sustain the railway and its ever ageing buildings, infrastructure, locomotives, carriages and wagons – for which the costs of maintenance and restoration are ever increasing.

On October 19, 2018, the new £200,000 interactive locomotive exhibition, SteamWorks! at Sheffield Park was opened, marking the completion of the first phase of the railway’s three-year £1.5 million National Heritage Lottery Fund-backed ASH (Accessible Steam Heritage) project, which aims not only to improve the display of classic locomotives but also to provide a wider educational and interactive experience for visitors. Taking pride of place on static display is none other than Stepney, alongside which is a full size mock-up of the locomotive where members of the public can get up close and operate the controls, view progress down the track and experience life on the footplate.

Society trustee Roger Kelly said: “SteamWorks! is designed to be both fun and educational for people of all ages, but particularly the young. It is after all they who hold the key to our future success both in terms of visitors and volunteers.”

Indeed, Stepney has been a children’s favourite for generations, if only because of its depiction as a character in its own right in the Reverend Wilbert Awdry’s Railway Series alongside Thomas the Tank Engine.

The railway has established a Stepney club within its children’s section: visit www.bluebell-railway.com/childrens-section/ for more details and to join.

That is not to overlook the enormous effort put in one weekend a month by the youngsters in the 9F club who are forever cleaning, polishing, repairing and painting. Aged between 11 and 16, members of the 9F club often use this as source of training and experience for entry into volunteer work – but mainly the idea is to have fun. The club has been the route into a Bluebell volunteering career for many including current plc chairman Chris Hunford.

The youngsters of today are the lifeblood for the success, preservation and continuance of all our heritage railways of tomorrow.

Now for the next 60 years

After the extension of the line to East Grinstead a period of consolidation was required. However, that did not stop the successful completion in the summer of 2016 of the first building phase of Operation Undercover and its Heritage Skills Centre on land adjoining the carriage and wagon works at Horsted Keynes.

This £1 million project will provide cover from the elements for up to 20 carriages awaiting restoration or repair: the Bluebell Railway has long been a market leader in the recovery of Victorian and Edwardian carriage stock, renovating coach bodies used for decades as bungalows, holiday homes or chicken coops to as-built condition.

It has long been the aspiration of the Bluebell to see a second main line connection added, with the restoration of the Ardingly branch, which closed on October 28, 1963.

For a brief spell afterwards, the branch was used occasionally to transport rolling stock to the Bluebell, the final movement along the line recorded on May 13, 1964 when ‘Terrier’ No. 32636 Fenchurch (LBSCR No. 72) became the last locomotive to arrive in steam before the heritage line was severed from the national network.

BR had given the Bluebell just four weeks to acquire Fenchurch, but Dr Beeching decreed that the locomotive should instead be reserved for six months.

Lifting of the Ardingly branch began on July 15, 1964, and reached Horsted Keynes by September 21. During the summer of 1968, Sheriff Mill viaduct, the condition of which was one of the reasons for the closure of the branch, was demolished as Mid Sussex District Council wished to straighten the bend on New Lane below. The Bluebell had been invited to buy the line in 1962, but could not afford BR’s asking price of between £25,000-£30,000 together with the £10,000 needed to maintain the viaduct. Options for bridging the Sheriff Mill gap as part of the mooted Western Extension Project by extending the embankments and using two second-hand bridge sections, are being pursued, and another major obstacle is the replacement of a short girder bridge. The branch’s Lywood Tunnel appears to be in good condition.

The western end had a second lease of life for carrying freight. An Amey Roadstone plant was established in Ardingly goods yard shortly after closure of the line, and was served by a daily freight working from Haywards Heath using the former down local line. Access to the up main and up local lines at Copyhold Junction has been severed. The new occupant demolished most of the station platforms, and track in the station was removed and a loop installed at the southern end of the former goods yard area. The station buildings remain, used as offices by the firm’s successor, Hanson Aggregates.

After the completion of the East Grinstead extension, Bluebell directors said the line would give itself a breathing space before embarking on such a major project. However, restoration of the Ardingly branch could give the Bluebell a presence in Haywards Heath and do for tourism in that town what it has done for East Grinstead, as well as a potential interchange with the London to Brighton line.

The Bluebell is now securing the asset so that a future extension to Haywards Heath remains a possibility, replacing fencing and carrying out ecological surveys.

Visitors inevitably ask if there is also the possibility of rebuilding the line south of Sheffield Park, over the vacant formation of Lewes that Madge Bessemer and the original revivalists had hoped to save.

The short answer is that the Bluebell now sees no commercial reason for a new push south. The railway does not own the trackbed, and a major cost struggle to get into Lewes because the land has been built over and the former brick viaduct has gone.

New LBSCR locomotives

As stated earlier, the founders hoped that the LBSCR line they saved would host as much of that company’s locomotive and rolling stock types as possible.

In October 2000, it was announced that a new H2 Brighton Atlantic would be built, replicating the last in service, No. 32424 Beachy Head, withdrawn in April 1958 and scrapped.

The boiler of the new 4-4-2 passed its hydraulic test last autumn, and it has been hoped to fit it to the frames so that the locomotive could be displayed for Bluebell 60th anniversary celebrations that had been scheduled for August 7-9 (see below).

However, Covid-19 has seen all work suspended on the project, and so the new Beachy Head will now appear later than planned.

In the autumn of 2019, the railway’s board, society and trust gave full endorsement to the Atlantic Group’s next scheme, the building of SECR E class 4-4-0 from scratch as a cost of £1.2 million.

The group has chosen No. 516 in original condition to replicate, and it is estimated the project, which will start as soon as Beachy Head is complete, will take 10-13 years to complete.

Group chairman Terry Cole said: “It would add a locomotive type widely used on the Southern Railway but which the Bluebell Railway currently doesn’t have: The pre-grouping 4-4-0. The chosen engine is No. 516 which was used as the ‘royal’ engine and kept in tip-top condition.”

Meanwhile, the railway is lining-up the next locomotives in its overhaul queue.

Work is currently in progress on Bulleid Battle of Britain Pacific No. 34059 Sir Archibald Sinclair. When that is completed, a start will be made on Fenchurch.

Then it will be the turn of the Maunsell Locomotive Society’s Schools V 4-4-0 No. 928 Stowe. Members of its owning group have been making progress with work off site while the Sheffield Park workshop is closed due to lockdown.

Next overhaul

The brake gearing has been refitted to the rolling chassis and the steam heating system has been fitted with all new steel piping. Cladding sections are being cleaned and painted by volunteers while the cab roof is being reskinned.

After that, the Bluebell will look at the next medium-sized overhaul, possibly H 0-4-4T No. 263 when its current running certificate is finished or GWR Dukedog 4-4-0 No. 9017 Earl of Berkeley, a veteran of the Cambrian Coast Line and real ‘odd man out’ in Southern territory but which, since its arrived in 1962 thanks to the efforts of the late Tom Gomm, has firmly established itself as part of the Bluebell furniture. Indeed, when saved for preservation, the Bluebell was the only line where it could run.

The beauty of the Bluebell fleet is that everyone will have their favourite locomotive, and therefore their own opinion on which should be restored to running order next.

Celebrations suspended

This year, the railway has geared itself up to celebrate its 60th anniversary, with a showpiece Steaming Through 60 gala weekend over August 7-9.

However, those celebrations have been postponed along with all other special events planned to date, because of the coronavirus pandemic.

The closure of the line due to lockdown has also placed on hold a planned programme to carry out an in-depth refurbishment and restoration programme to restore the line’s ‘jewel in the crown’, Horsted Keynes station.

The first stage of the project has been to undertake a comprehensive survey of everything from the chimney stacks down to the railway tracks. The 75-page survey has revealed deterioration in the station fabric and the platforms, but concludes that the station is overall basically sound. The full cost of restoring the station to its 1930s glory is estimated to be over £1 million, but plans to launch a Diamond Jubilee year appeal to members and supporters to raise at least £500,000 of the cost have now been delayed because of COVID-19.

Instead, as previously reported in issues 266 and 277, the railway has joined many other heritage lines throughout the UK in launching emergency appeals to cover overheads during the lockdown period, in order simply to survive, following its closure on March 20.

As we closed for press, the Government had started to ease lockdown restrictions, but no firm date had been set as to when places of entertainment including heritage lines could resume operations.

Public support

However, the public has not forgotten 60 years of Bluebell magnificence, for by the end of May, more than £250,000 had been donated towards an initial target of £300,000. Officials revealed that there had been at least 1500 individual donations ranging from a few pounds from children offering their pocket money to several thousand pounds from members and supporters.

The railway’s fundraising organiser Trevor Swainson said: “The totals include a commitment by two individuals who wished to remain anonymous to jointly donate £5000 including Gift Aid if the total reached £195,000. That has now happened.”

The railway set the £300,000 target based on financial modelling. While fare income from passengers is its main source of revenue each year, the railway also relies on sales of food and drink at its cafes and restaurants, shop purchases, weddings, special railway charters and filming location fees to provide enough money to restore its historic locomotives and carriage.

A railway spokesman said: “We are now looking at the logistics and practicalities of reopening. We are examining how to ensure social distancing and provide health protection while operating as a heritage railway.”

Survival instincts

Of course, if the lockdown restrictions continue beyond the summer months, it is likely that the Bluebell, in common with all other heritage lines, will need to raise that target even further. To many, it all but seems that those pioneering times of the late Fifties and early Sixties to see steam and branch lines survive against all odds have now back with us and with a sharp vengeance.

To support the Bluebell’s emergency appeal, visit https://uk.virginmoneygiving.com/fund/support-bluebell to compensate for the loss of the Steaming Through 60 gala weekend in August, the railway is to hold a virtual celebration of its fabulous 60 years of operation in August.

Robert Hayward, chairman of the Bluebell Railway’s Diamond Anniversary steering group, said: “The pragmatic decision not to hold the event as previously planned allows the Bluebell Railway to focus its efforts on reopening. We will be holding a virtual event this August and are currently working on various ideas for the event because we are still going to celebrate 60 years of operating as a heritage line.”

The railway is asking its members with model railway layouts to film locomotives in action to produce a ‘virtual gala’ to replace this year’s cancelled spring and summer events. The virtual gala will be posted on the railway’s YouTube channel to view.

Again, with youngsters in mind, the line’s education department is producing a series of online Storytime videos for children. The railway-related stories have been selected and read by volunteers from the department before being uploaded to the YouTube channel.

The department’s Ruth Rowatt said: “Storytime with Bluebell Railway is a nice way to keep our younger visitors informed and to keep the railway in their hearts and minds. Many children were looking forward to visiting Stepney and all his friends at the Bluebell Railway this spring. I wanted to let them know that we at the railway are thinking of them and looking forward to welcoming them when we reopen.”

The real-life 60th annual gala will now be rearranged for next year. Robert added: “New opportunities may be available to us in 2021 that are not possible now. Next year’s event will be on a date to be agreed.”

As we closed for press, all events from September until the end of December were under review, includes the planned debut SteamLights season of illuminated trains, as pioneered by the Dartmouth Steam Railway which accordingly won a major Heritage Railway Association award in February. The Bluebell is now working on the practicality of holding SteamLights in addition to its popular Santa specials and festive dining trains.

Several of the views from the Bluebell Railway Archive are included in a new book, Bluebell Railway: Sixty Years of Progress 1960-2020, available from the online shop at www.bluebell-railway.com/product/bluebell-railway-sixty-years-of-progress-1960-2020/ which is operating during lockdown.